Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: illegible_scribble

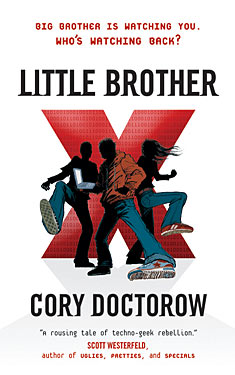

Little Brother

| Author: | Cory Doctorow |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2008 |

| Series: | Little Brother: Book 1 |

|

0. Lawful Interception |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Near-Future Cyberpunk Dystopia |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Marcus, a.k.a "w1n5t0n," is only seventeen years old, but he figures he already knows how the system works–and how to work the system. Smart, fast, and wise to the ways of the networked world, he has no trouble outwitting his high school's intrusive but clumsy surveillance systems.

But his whole world changes when he and his friends find themselves caught in the aftermath of a major terrorist attack on San Francisco. In the wrong place at the wrong time, Marcus and his crew are apprehended by the Department of Homeland Security and whisked away to a secret prison where they're mercilessly interrogated for days.

When the DHS finally releases them, Marcus discovers that his city has become a police state where every citizen is treated like a potential terrorist. He knows that no one will believe his story, which leaves him only one option: to take down the DHS himself.

Download this book for free from the author's website.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

I'm a senior at Cesar Chavez, High in San Francisco's sunny Mission district, and that makes me one of the most surveilled people in the world. My name is Marcus Yallow, but back when this story starts, I was going by w1n5t0n. Pronounced "Winston."

Not pronounced "Double-you-one-enn-five-tee-zero-enn"— unless you're a clueless disciplinary officer who's far enough behind the curve that you still call the Internet "the information superhighway."

I know just such a clueless person, and his name is Fred Benson, one of three vice-principals at Cesar Chavez. He's a sucking chest wound of a human being. But if you're going to have a jailer, better a clueless one than one who's really on the ball.

"Marcus Yallow," he said over the PA one Friday morning. The PA isn't very good to begin with, and when you combine that with Benson's habitual mumble, you get something that sounds more like someone struggling to digest a bad burrito than a school announcement. But human beings are good at picking their names out of audio confusion—it's a survival trait.

I grabbed my bag and folded my laptop three-quarters shut—I didn't want to blow my downloads—and got ready for the inevitable.

"Report to the administration office immediately."

My social studies teacher, Ms. Galvez, rolled her eyes at me and I rolled my eyes back at her. The Man was always coming down on me, just because I go through school firewalls like wet kleenex, spoof the gait-recognition software, and nuke the snitch chips they track us with. Galvez is a good type, anyway, never holds that against me (especially when I'm helping get with her webmail so she can talk to her brother who's stationed in Iraq).

My boy Darryl gave me a smack on the ass as I walked past. I've known Darryl since we were still in diapers and escaping from play-school, and I've been getting him into and out of trouble the whole time. I raised my arms over my head like a prizefighter and made my exit from Social Studies and began the perp-walk to the office.

I was halfway there when my phone went. That was another no-no—phones are muy prohibido at Chavez High—but why should that stop me? I ducked into the toilet and shut myself in the middle stall (the farthest stall is always grossest because so many people head straight for it, hoping to escape the smell and the squick—the smart money and good hygiene is down the middle). I checked the phone—my home PC had sent it an email to tell it that there was something new up on Harajuku Fun Madness, which happens to be the best game ever invented.

I grinned. Spending Fridays at school was teh suck anyway, and I was glad of the excuse to make my escape.

I ambled the rest of the way to Benson's office and tossed him a wave as I sailed through the door.

"If it isn't Double-you-one-enn-five-tee-zero-enn," he said. Fredrick Benson—Social Security number 545–03–2343, date of birth August 15 1962, mother's maiden name Di Bona, hometown Petaluma—is a lot taller than me. I'm a runty 5'8", while he stands 6'7", and his college basketball days are far enough behind him that his chest muscles have turned into saggy man-boobs that were painfully obvious through his freebie dot-com polo shirts. He always looks like he's about to slam-dunk your ass, and he's really into raising his voice for dramatic effect. Both these start to lose their efficacy with repeated application.

"Sorry, nope," I said. "I never heard of this R2D2 character of yours."

"W1n5t0n," he said, spelling it out again. He gave me a hairy eyeball and waited for me to wilt. Of course it was my handle, and had been for years. It was the identity I used when I was posting on message boards where I was making my contributions to the field of applied security research. You know, like sneaking out of school and disabling the minder-tracer on my phone. But he didn't know that this was my handle. Only a small number of people did, and I trusted them all to the end of the earth.

"Um, not ringing any bells," I said. I'd done some pretty cool stuff around school using that handle—I was very proud of my work on snitch-tag killers—and if he could link the two identities, I'd be in trouble. No one at school ever called me w1n5t0n or even Winston. Not even my pals. It was Marcus or nothing.

Benson settled down behind his desk and tapped his class ring nervously on his blotter. He did this whenever things started to go bad for him. Poker players call stuff like this a "tell"— something that lets you know what's going on in the other guy's head. I knew Benson's tells backwards and forwards.

"Marcus, I hope you realize how serious this is."

"I will just as soon as you explain what this is, sir." I always say "sir" to authority figures when I'm messing with them. It's my own tell.

He shook his head at me and looked down, another tell. Any second now, he was going to start shouting at me. "Listen, kiddo! It's time you came to grips with the fact that we know about what you've been doing, and that we're not going to be lenient about it. You're going to be lucky if you're not expelled before this meeting is through. Do you want to graduate?"

"Mr. Benson, you still haven't explained what the problem is—"

He slammed his hand down on the desk and then pointed his finger at me. "The problem, Mr. Yallow, is that you've been engaged in criminal conspiracy to subvert this school's security system, and you have supplied security countermeasures to your fellow students. You know that we expelled Graciella Uriarte last week for using one of your devices." Uriarte had gotten a bad rap. She'd bought a radio-jammer from a head shop near the 16th Street BART station and it had set off the countermeasures in the school hallway. Not my doing, but I felt for her.

"And you think I'm involved in that?"

"We have reliable intelligence indicating that you are w1n5t0n"—again, he spelled it out, and I began to wonder if he hadn't figured out that the 1 was an I and the 5 was an S. "We know that this w1n5t0n character is responsible for the theft of last year's standardized tests." That actually hadn't been me, but it was a sweet hack, and it was kind of flattering to hear it attributed to me. "And therefore liable for several years in prison unless you cooperate with me."

"You have ‘reliable intelligence'? I'd like to see it."

He glowered at me. "Your attitude isn't going to help you."

"If there's evidence, sir, I think you should call the police and turn it over to them. It sounds like this is a very serious matter, and I wouldn't want to stand in the way of a proper investigation by the duly constituted authorities."

"You want me to call the police."

"And my parents, I think. That would be for the best."

We stared at each other across the desk. He'd clearly expected me to fold the second he dropped the bomb on me. I don't fold. I have a trick for staring down people like Benson. I look slightly to the left of their heads, and think about the lyrics to old Irish folk songs, the kind with three hundred verses. It makes me look perfectly composed and unworried.

And the wing was on the bird and the bird was on the egg and the egg was in the nest and the nest was on the leaf and the leaf was on the twig and the twig was on the branch and the branch was on the limb and the limb was in the tree and the tree was in the bog—the bog down in the valley-oh! High-ho the rattlin' bog, the bog down in the valley-oh—

"You can return to class now," he said. "I'll call on you once the police are ready to speak to you."

"Are you going to call them now?"

"The procedure for calling in the police is complicated. I'd hoped that we could settle this fairly and quickly, but since you insist—"

"I can wait while you call them is all," I said. "I don't mind."

He tapped his ring again and I braced for the blast.

"Go!" he yelled. "Get the hell out of my office, you miserable little—"I got out, keeping my expression neutral. He wasn't going to call the cops. If he'd had enough evidence to go to the police with, he would have called them in the first place. He hated my guts. I figured he'd heard some unverified gossip and hoped to spook me into confirming it.

I moved down the corridor lightly and sprightly, keeping my gait even and measured for the gait-recognition cameras. These had been installed only a year before, and I loved them for their sheer idiocy. Beforehand, we'd had face-recognition cameras covering nearly every public space in school, but a court ruled that was unconstitutional. So Benson and a lot of other paranoid school administrators had spent our textbook dollars on these idiot cameras that were supposed to be able to tell one person's walk from another. Yeah, right.

I got back to class and sat down again, Ms. Galvez warmly welcoming me back. I unpacked the school's standard-issue machine and got back into classroom mode. The SchoolBooks were the snitchiest technology of them all, logging every keystroke, watching all the network traffic for suspicious keywords, counting every click, keeping track of every fleeting thought you put out over the net. We'd gotten them in my junior year, and it only took a couple months for the shininess to wear off. Once people figured out that these "free" laptops worked for the man—and showed a never-ending parade of obnoxious ads to boot—they suddenly started to feel very heavy and burdensome.

Cracking my SchoolBook had been easy. The crack was online within a month of the...

Copyright © 2008 by Cory Doctorow

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details