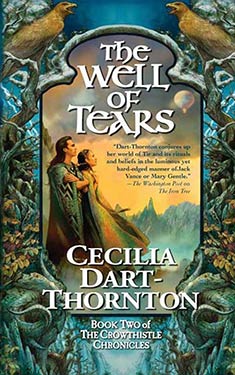

The Well of Tears

| Author: | Cecilia Dart-Thornton |

| Publisher: |

Pan Macmillan, 2005 Tor, 2005 |

| Series: | Crowthistle Chronicles: Book 2 |

|

1. The Iron Tree |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The beautiful maiden Jewel is the center of her parent's joy. She is the embodiment of their true love and she has grown up surrounded by peace and love in abundance.

Jewel's world cruelly shatters when her parents are suddenly killed and she and her uncle Eoin are forced to flee. Leaving the only home she has ever known, Jewel learns that her parents, caught in a tangle of a tragic prophecy, had hidden in the marshland for years to protect the secret knowledge that Jewel is the last of the line of the Janus Jaravhor, the dreaded sorcerer of Strang. That she might be the one person in the world who could unlock the mysterious Dome that is told to hold all of Janus's secrets. And that King Maolmordha now knows of her existence and will stop at nothing to find her.

Pain and loss follow and Jewel must make her way alone. Rescued by a traveling band of Weathermasters, exalted magicians who control the heavens for the rich and powerful, she is taken to High Darioneth and is accepted into this tightly knit community.

Not just accepted, but loved, for one of the young weathermasters beheld her and his heart was lost.

Jewel is left with the promise of true love and a powerful secret. But which path will she choose--and who will suffer if she makes the wrong choice?

Excerpt

Chapter One Prophecy

For five nights and five days Jewel and Eoin fled on foot across sparsely wooded countryside, northward from the Great Marsh of Slievmordhu. Often they looked back, scanning the uninhabited landscape to see if anything was coming after them.

They could not discern any obvious signs of pursuit, but they made haste, nevertheless.

By day, sunlight silvered the ferns carpeting the bracken-woods, where tree-boles leaned against their own shadows. By night, the far-off constellations were gauzy scarves of white mist sewn with nearer stars as brilliant and hard as splinters of glass. The dark hours were also the wighting hours, their wind-murmuring quietude randomly punctuated by dim sounds of sobbing, thin, weird pipe-melodies, unintelligible singing, or bursts of rude, uncontrollable laughter.

The rations the wayfarers carried in their packs were scant, and dwindling fast. Their departure from the marsh had been precipitous; in their haste to escape before King Maolmórdha's troopers arrived, there had been no time to throw anything more by way of provisions into the canoe than a few lotus-corm loaves, some packets of dried fish, and a couple of leathern flasks.

"I'll catch a tasty treat for your supper this evening, little one," Eoin said to Jewel, in an effort to coax her out of her gloom, but she answered not a word. The girl spoke rarely, and her eyes, her blue eyes like two amethysts in caskets lidded with lapis lazuli, gazed out with a dreary and haunted look.

It was agonizing to dwell on the recent past, yet somehow she could not prevent herself from doing so. She had lost nearly everything she loved, everything that was familiar to her: family, home, pets, and possessions. Seeking for some comfort, Jewel glanced over at Eoin, her step-uncle and protector, for whom she felt an earnest fondness, knowing nothing of his role in her downfall.

As they plodded onward, the marshman was himself buried deep in thought, endlessly rebuking himself for the part he had played in Jewel's suffering. Had Eoin never revealed Jarred's identity to King Maolmórdha's minions, the king would not have learned that Jewel's father was descended from the notorious Sorcerer of Strang. Then the royal cavalry would not have come thundering along the road to the Great Marsh of Slievmordhu. Their pursuit would not have triggered Lilith's madness, and she would not have run to the cliff-top in a blind panic. Jarred would not have died trying to save his wife, and twelve-year-old Jewel would not have been forced to flee from her home.

Eoin blamed himself for all these tragedies. None of this would have happened if he, displaying a pettiness unworthy of a truly upright man, had not informed against his rival. Driven by his own vain jealousy, he had brought this fate of loss and exile upon the child he doted on, daughter of the woman he adored--and now he must do what he could to make reparation, although he ached, as if the fibers of his sinews had been shredded.

The marshman unhitched the slingshot from his belt and couched a stone in the strap. He was ready when, with the whirring of a hundred rapid spinning wheels, a brace of grouse flew up from the ferns beneath their feet. After whirling the weapon around his head, he let fly. He was lucky; a plump bird fell, wounded. Eoin wrung the bird's neck, plucked it, and roasted it over a campfire on the banks of a narrow stream. Succulent juices ran from the meat, but as enticing as the meal appeared, it tasted no better than sand in the melancholy mouths of the diners.

As if to punish himself, Eoin brought to mind the uncanny funeral he had lately witnessed in the city of Cathair Rua: a mock, staged affair, conducted by eldritch wights, the coffin containing a corpse whose face was the exact image of his own. Eoin had comprehended at once that he had viewed a prophecy of his own death; within a twelve-month he would perish. Somehow, as he brooded by the campfire, the prospect lent him some relief. If only he could bring Jewel to some safe haven before his final hour, he would be quite glad to lie down, relinquish his gut-wrenching remorse, and find peace.

After the joyless meal was over, Eoin went down to the stream to refill the water flasks.

As he knelt by the water, the flesh clenched on the nape of his neck and unaccountable fear shivered through him. A harsh voice had called from the brakes of fern, a voice like a cry from the long, hoarse throat of some wild bird.

Raising his head apprehensively, he saw a strange entity watching him from the other side of the stream. It was a stunted, man-like thing, strongly built and doughty. Its umber tunic and leggings were so ragged they appeared to be fashioned from withered bracken, and its frizzled hair was as russet as the sap-starved leaves of Autumn. Its eyes were bulbous, outlandishly huge, and they rolled beneath its shaggy red brows like the eyes of a wrathful bull.

"How dare ye come here slaughterin', ye miscreant?" it growled. "The wild creatures in this place are under my guardianship. If nuts and blackberries sustain me, that am their custodian, should they not be good enough for you? Step over to this bank, and I'll show you the victuals I gather."

Eoin guessed this was the Brown Man of the Muirs, a wight he vaguely recalled from old tales. As far as he could remember, the wight forbade hunting in its own domain. Horror engulfed Eoin, that he had offended an eldritch being, and for a moment he was daunted. Then it came to him that he was acting like a coward and, despising himself, he sprang up and set his foot on a tussock, preparing to jump across the stream. As he did so, he heard Jewel's young voice from somewhere behind him, crying out pitifully, "Uncle Eoin, where are you?"

He wheeled about. The little girl was running toward him, her hair and gown streaming behind her on the wind.

"Go back! Go back!" Eoin warned, but when he turned back again the Brown Man had disappeared. "Did you see it?" Eoin asked, as Jewel rushed up beside him.

"See what?" demanded Jewel. She tossed back the dark tangle of her tresses and folded her arms across her chest.

"That was the Brown Man of the Muirs, if I'm not mistaken," said Eoin, craning his neck to peer in amongst the crochet of fronds on the opposite bank. "He bade me cross the stream and join him, saying he would show me how to find nuts and berries. Come, let us ford the brook and seek him."

"Are you mad?" shouted Jewel disbelievingly. "If 'twas indeed the Brown Man, then 'twas only the running water that saved you! If you had crossed over, the wight would have torn you apart and not even your druid-sained amulet would have protected you!"

Bewildered, the marshman shook his head.

"Come away," said the little girl, her mournfulness now replaced by anger, "and hunt no more. Do you wish that I should lose you, too?"

Then, as suddenly as her mood had changed, it changed again. The light in her eyes dulled and her hands dropped listlessly by her sides.

Strung up on a gallows of jealousy, betrayal, and premonition, Eoin felt guilt tighten like a noose around his gullet. The child's evident wretchedness pained him excruciatingly. It was he who was to blame for her bereavement and exile, no one else.

"No," he mumbled. "Let us go on."

Once, as evening deepened to night and they passed through a young oak wood, they spied a twinkling of lights through the trees and caught the babble of voices. Not wishing to be discovered by bandits, they crept forward silently. There in a clearing they beheld a scene of feasting and revelry set out on the greensward under the stars: a long table, garlanded with moon-roses, laden with dishes piled high with delectable fare. As the two mortals cautiously approached, musicians struck up a merry jig and the guests began footing it around the table.

Marvelous to look upon were these dancers and musicians, some as fair as flowers, elegant, silk-haired, clad in rainbows of finery. Others were foul nightmares, squat as toadstools, crooked and lopsided as trees rooted on a windswept sea-cliff, bloated as leeches, quick as rats, long-legged, gangling, and knock-kneed as newborn foals, grinning like pumpkin lanterns, hopping like frogs, graceful as cats, scowling like belligerent gargoyles.

Knowing full well that they looked upon a gathering of no mortal creatures, Jewel and Eoin scarcely dared breathe, lest they betray their presence. Eldritch wights could not bear to be spied upon, and might exact some terrible revenge for such a crime.

Slowly the intruders backed away, but an incautious step snapped a twig. In that instant the twinkling lights went out as if the eyeballs of the mortals had been gouged from their sockets. Simultaneously the strains of music were cut off in mid-bar, and the babble of voices stopped in mid-word. All was silence and darkness.

Fortunately, the stars let down enough filaments of light through the oak leaves for the wayfarers to relocate their forest trail. Soon they were on their way once more, putting as much distance as possible between themselves and that spooky place before weariness overcame them and they made camp for the night.

Eleven days after the wayfarers had fled the Great Marsh of Slievmordhu, they found themselves in open country that climbed to meet the rounded shoulders of the Border Hills. Eoin had cut a staff of blackthorn-wood for himself, and a shorter length for Jewel. Using these for support, they plodded up a gentle slope of turf that had been cropped short by deer and wild goats, a smooth greensward strewn with low boulders and occasional clumps of the weed crowthistle.

Glancing ahead, Jewel fancied they were ascending a stairway to the sky. Out of the northwest, low, livid rainclouds were moving swiftly eastward, heavy with rain. Where sunlight struck them, they boiled out into puffs of luminous dazzle, pristine pillows of steam. Farther east, they broke up into islands in a blue sea that faded from cobalt at the zenith, merging to a haze of softest gray at the horizon.

A drawn-out sighing greeted them as they reached the top of a ridge, the sound of cool breezes breathing through a copse of beeches that crowded close together. Magpie-larks swooped, uttering their rusty-gate-hinge calls. As the wayfarers walked over the spine of the ridge and down into the copse, the trees loomed taller, towering overhead. Their wide-reaching boughs nodded gently, whispering; their shade was cool and dappled, the ground patterned with tender green blades and butter-curls of leaves, gold and brown. A path of sorts went winding between the boles. Here they rested for a while, seated with their backs against corrugated bark.

"When we come down out of these hills," said Eoin presently, "we shall leave Slievmordhu behind us. These are the borderlands. Narngalis lies ahead."

Solemnly, Jewel nodded.

Throughout their journey together, Eoin had never seen her smile. This was not to be wondered at. There was no reason for either of them to be mirthful. Wretchedness and weariness weighed upon him. He wondered how much Jewel knew, or guessed, about the part he had played in the ruination of her family, of her life. As ever, his thoughts flickered miserably back over the recent series of events, precipitated by a single, spiteful act born of his vindictiveness. Privately--so as not to cause further distress to Jewel--he pined grievously for Lilith. He was consumed by an unassuageable longing to return to that pivotal moment in time when he had stepped into the palace, so that he might erase his errors and change everything.

Having swallowed a mouthful of water, he and Jewel got up and continued on their way.

The colors of the wayfarers' raiment blended with those of the landscape. This was because they were covered in much of it. The marshman, gangling and long-jawed, was clad in the same gear he had been wearing throughout his helter-skelter ride from Cathair Rua. His soft leather leggings were travel-stained; his fine linen shirtsleeves had been rent, in places, by the protruding spurs of low vegetation through which he had pushed in haste. The gray stocking-cap he had purchased from the landlord of the "Ace and Cup" in Cathair Rua had fallen off long ago. The reddish knee-length tunic, now dirty brown, was coming unstitched at the seams. Its cheap woolen fabric was thin, and provided little warmth. When he woke from his brief slumbers, he was always shivering. His boots, however, were stout, and well endured the trials of swift passage across rough terrain.

The smudges on the face of the twelve-year-old girl walking at his side could not obscure her beauty. Her hair was as black and shiny as a handful of acacia seeds, and the dark locks clung together in a singular fashion, so that the tapered ends spiked forth like the new-budding tips of a fir tree. Narrow was her waist, no wider than the thigh of a grown man. Her skin was peaches-by-firelight; her mouth was the softly curved petal of a pink rose. She wore a linen kirtle beneath a woolen gown, and over her shoulders a traveling-cloak, lined with fur, clasped with a brooch of bronze. The matching traveling-hood hung behind her shoulders. Like her step-uncle, she had lost her other headgear; her scarf was dangling from a twig somewhere, having been swept from her scalp during that first frantic scramble away from the northern shores of the marsh. Her boots, like Eoin's, were well made. In happier days he had purchased them for her, as a present, from the most reputable cobbler in Cathair Rua.

Trudging beside Jewel along the verdant vales and wooded slopes of the Border Hills, Eoin was glad of his gift to the child. It was his fault she had been hounded from her home in search of an uncertain future, his fault, indirectly, that she was orphaned. The irony was that of all things that lived in Tir, he cared most for her.

The two wayfarers met no human being in these high places, only the mortal creatures of the wilderness, such as birds, insects, reptiles, beasts of hoof and horn. Sometimes in the gloaming they spied more wights--whether seelie or unseelie they could not tell, but they kept their distance. If human beings had ever dwelled in the Border Hills, they were long gone.

These were lonely lands.

As they journeyed, Eoin never let down his guard. The fear of pursuit remained strong in him still, accompanied by the awareness of clandestine eldritch activity all around. Furthermore, he was heavily burdened with a sense of responsibility for his step-niece, a desire to protect her from all harm, both because he loved her and because while defending her he could deceive himself that he was relieving his guilt.

He was unable to bring himself to talk to his young companion about the terrible events that had befallen her, never tried to break her long silences. Above all, he could not bear to incur the child's hostility by revealing the role he had played in her family's tragic fate. Of course, she had been audience to her father's harsh words to Eoin shortly before Jarred's death, and she must have perceived there was more ill-feeling between them than usual, but she never confronted Eoin with demands to be told exactly what had happened. Perhaps she believed it was all too appalling to contemplate and was best left unvoiced. Perhaps her overwhelming grief clouded her reason. For Eoin's part, his remorse and self-reproach prevented him from broaching the subject with her.

At nights he did not sleep, preferring to keep vigil. During the days he and Jewel would halt at noon, when he would fall into a dreamless slumber for a few hours. Relentlessly his body stayed taut as a spring, his muscles involuntarily twitching at random intervals, ever ready to react to the first hint of peril; and his sharp eyes flicked back and forth, noting the shape of every boulder, the motion of every bough and pool of shade. He watched, also, for suggestions of disturbance amongst the wild fauna of the hills, which might provide clues to impending danger.

Crickets whirred rhythmically in the seeding grasses of Autumn, counter-pointed by the dark, oceanic soughing of the wind through drifts of living leaves. The wayfarers were passing through another scattered beech wood when two events occurred simultaneously. Although they scarcely engendered any sound, alarm screamed through the skull of Jewel's guardian.

Not far off to the right, a flock of wood-pigeons fountained into the air, their wings flapping like a multitude of white hands waving farewell. And a vertical litheness detached itself from a tree-bole before gliding into a thicket.

Instantly, Eoin spun around. Jewel had been dawdling behind him. Now he discovered that she had dropped back several paces and was leaning over, intent on examining some weed or wildflower sprouting from the crevice of a mossy boulder.

"Hide!" Eoin hissed through his teeth, signaling urgently to reinforce his words. Surprise flared momentarily across the girl's features; then she obeyed, dropping out of sight amid the lush foliage of a bank of foxgloves.

Where Eoin had stood, he stood no longer. He, too, had thrown himself to the ground, and now lay rigid. Between thin wands of tussock-grass he could see the figures of men who might well have been mistaken for part of the countryside, had they not been on the move. His first thought was that the king's soldiery had discovered Jewel's existence, had somehow tracked her down, and were quartering the hills in their search for her. Almost at once he realized the folly of such an assumption--the men he was watching were making their way on foot, not on horseback. Neither were they clad in the uniforms of the Royal Guard, but in motley garb, dun-hued, their visages largely obscured by leather helms. As well, they advanced with an easy stealth that could only be learned from practice in the wilderness, never by routine drill in the training-yards of a military barracks.

These men were bandits--or, worse, the warped mountain-swarmsmen known as Marauders.

Most likely Marauders, Eoin concluded to himself, using the shelter of the Border Hills to conceal their passage toward Grïmnørsland and the coast. The men, spread across a wide front, were stepping noiselessly between the trees. Soon, one of their number appeared from behind a scabrous beech growing quite close to Eoin, and the marshman held his breath. Lie tranquil, Jewel. His lips formed the words without uttering them--yet he knew with certainty that the child would lie immobile, unflinching. She was not one to startle easily, and he had great store of respect for her common sense.

The walker went past without spying the refugees in their makeshift coverts.

The farther-off Marauders were no more than a shaking of leaves, a mellow crunch of dry seed-pods underfoot, an erect form ducking beneath a bough. Those passing closer to Eoin's hiding-place resolved themselves into unsavory-looking fellows whose belts and baldrics sported a vast array of portable weaponry. Some carried bundles on their shoulders. They did not speak to one another, but now and then one would cup his hands around his jowls and make a call like an owl, a signal to his accomplices.

Foolish, thought Eoin. Owls are nocturnal....

Eoin counted eighteen mountain-brigands. The wind began to rise as the last of them disappeared into the woods to the west and blended into the scenery. When the sounds of their excursion had died away, Eoin dared to draw a deep breath and raise his head.

As if struck in the face, he reeled.

He had been mistaken. Buffeted by a swirling tide of golden leaves, a nineteenth swarmsman was following in the wake of the rest. His footfalls as muted as a deer's, the Marauder happened to be making straight for the weedy bank where the child lay concealed. At any moment, he must surely stumble over her.

Jewel, curled up in her bower of late-blooming foxgloves like some elfin princess in a castle of purple turrets, heard someone approaching. Judging by the tempo and style of the pace, she guessed it was not Eoin. Notions of incorporeal footsteps flitted through her consciousness, and in that moment she believed her mother's madness had descended upon her.

Then the stately flower-towers, dripping with clusters of hyacinthine bells, shuddered. They swished aside, and a thick-set, bearded fellow stood looking down at Jewel. She kept her wits and did not cry out, even when a yellowish grin split the beard and he bent to seize her.

Something came flying out of the sky, landed on his shoulders, and knocked the man over. Jewel rolled aside with well-timed presence of mind--he came crashing down on his face, into her nest, with Eoin riding atop him. The marshman grabbed the brigand in a stranglehold, so that he had no breath to summon his comrades--but the bearded fellow was no weakling. After a manic struggle he managed to throw off his attacker and twist around to confront him. Eoin jumped to his feet, fists at the ready. The rustling of windblown leaf-showers drowned out the noise of combat, and the swarmsman gasped for air, too short of breath to cry out to his distant comrades, who by then had passed out of earshot. He lumbered upright and lunged forward. The two men locked together in deadly combat while Jewel frantically cast about for a stick or stone with which she might assail their enemy. It was obvious Eoin was no match for this thick-thewed ruffian.

Laying hands on her blackthorn stick, the child thwacked the Marauder mightily across his back. Emitting a grunt of astonishment, he turned his head to see what harassed him, and at the fulcrum of his distraction, Eoin gave a sudden, hard shove. Off balance, the brigand stepped backward. His boot-heel slipped on a small rock overgrown with grasses and he toppled for a second time, dragging his opponent with him. Yet when he hit the ground his arms loosened and fell by his sides, flaccid as rope. He ceased to move. A scarlet worm crawled from the hollow of his left temple, where his lopsided skull had made contact with the mossy boulder whose crevices harbored wild orchids.

Staggering, gasping, Eoin stood up. The staff dropped from Jewel's fingers. She glanced from her step-uncle to the prone man, and back again. Her vivid eyes seemed huge and luminous in her pearl of a face. Underneath, they were smeared with bruised arcs, like the juice of nightshade berries. A tremor ran through her lower lip.

Eoin grasped her by the hand. "We must depart with all haste," he rasped, his voice cracking with exertion, "before they discover this man is missing, and come seeking him."

He grabbed their packs and away they sped, to the north as ever; far from the Marauders' westward path, far from King Maolmórdha's soldiers, far from the scene of Eoin's treachery, though he was never able to outrun his guilt.

A strewing of birds shivered across the sky, flashing from dark to light with every beat of their wings. Leaves, detached from their stems by the cool touch of the season, spooned down cascades of air, like tiny boats.

The wayfarers went on at a cracking pace, without their usual brief halts for respite. Jewel had made no complaint, but it was obvious to Eoin that she was exhausted. When the deepening twilight began to pool in the valleys, they finally made camp in a grove of lime trees on the eastern slope of a hill. Radiance poured, green and gold, through the foliage. Amongst the million upon zillion floating points of light and color that were the leaves, the intertwining trunks and branches could be glimpsed, standing out starkly, as if drawn with charcoal strokes.

The marshman left the tinderbox in the leather pack and did not light a fire, in case Marauders lingered in the vicinity. A column of smoke, no matter how ethereal, would surely attract their attention. Neither he nor Jewel had much appetite for the fragmented remnants of dry foodstuffs that remained.

"This night I shall catch a coney or two," said Eoin without enthusiasm, breaking a long silence between them. "We are far from the haunts of the Brown Man."

The child nodded.

"Do you think he died, that fellow with the knives?" she said, after a while.

"He did not," answered Eoin. "He was breathing. I saw his chest rise and fall. The senses were knocked out of him, and with luck he'll remember naught of what happened, but he lived, and maybe lives still."

"I am glad."

"You should not be. He saw you--"

"Why does that matter?" she asked.

He pondered, then shook his head. "I am all a-muddle," he said wearily, rubbing his eyes. "It matters not, after all. The people of the marsh would never betray you. They will swear Jarred had no child."

Listlessly, Jewel picked at the ripening seeds of panicum grass growing within her reach. "I do not understand," she said.

"What is it you do not understand?"

"My father--"the girl paused, drew a long breath, and continued--"my father explained to me why I had to leave the marsh. But it all happened so quickly and there was no time to ask questions. And then he was gone--" Again, she broke off. Her knuckles bleached as she clenched her small hands. "I do not properly understand why the marsh-folk must not tell Outsiders that my father had a daughter. And why would King Maolmórdha send his soldiers to capture me, if he found out I exist? And if these soldiers took me, what would happen to me?"

She reached beneath the front of her gown and extracted two pendants. One, like a creamy coin, hung around her neck on a fine silver chain; the other, an extraordinary jewel, depended from links of white-gold. Reflected rays shot from the jewel. Fire-of-snow, it twinkled, fascinating, brilliant.

"Is it something to do with this?" asked the child, holding up the precious stone. "Where did it come from? How did my father obtain such a marvel? To whom does it belong?"

"That pretty rock belongs to you and no other. Your father managed to take it out of the boughs of the Iron Thorn that grows in Cathair Rua. It belonged to him by right of birth. His father's father was Janus Jaravhor, the Sorcerer of Strang, who cast the bauble into the tree, where it could only be retrieved by one of his descendants."

Jewel fingered the other pendant strung about her neck. It was an amulet, an unpretentious disc of bone engraved with two interlocking runes. "My father gave me this amulet. He used to tell me it would keep its wearer from hurt. But I know that after all, 'tis not the amulet that protects me. 'Tis the blood of that sorcerer, flowing in my veins."

"What?"

"In faith. My father revealed the truth to me the last time I saw him, before he went searching for my mother. Naught in the entire world could harm me, or him." The child's face darkened. "Save only for one thing, as has now been discovered."

She was referring to the fact that just before Jewel and Eoin had fled from the marsh, Cuiva, the White Carlin, had told them how she had discovered Lilith lying dead on a narrow ledge that jutted below the edge of the precipice. Jarred, having tried to reach his wife, was lethally impaled upon an upthrusting, jagged branch of mistletoe an arm's length away, his fingertips lightly brushing Lilith's face.

Slowly, Eoin assimilated Jewel's astounding revelation about the disc of bone.

So, he thought, that is why Jarred remained unscathed after our scrimmage. That is why he never took harm from the marsh-wights. I believed it was all due to the amulet. Ardently I wanted to possess that talisman, until he bestowed it on the child. And as it turns out, the power was never in it after all!

It was curious, the way Jarred had met his fate, curious, terrible, and unbearably sad. A branch of mistletoe, sharp as a spear, must have been the only material in the world capable of causing harm to a near-invulnerable descendant of Janus Jaravhor. Since then the child, as far as anyone knew, was the sole heir of the malign Sorcerer of Strang. Anew, remorse struck through Eoin like a bolt of pure ice.

Jewel is armored by her ancestry, the marshman ruminated to himself, and on hearing that news I am now blithe! Yet she must beware...

"Aye," he said softly, "and because of that same heritage of the blood, you alone possess the ability to unseal the Dome of Strang, and reveal all its hidden treasures. That is why King Maolmórdha would seize you, if he knew of you. You must not tell anyone who you are."

But Jewel was scarcely heeding his words. Deliberately, she was staring at the amulet of bone. She pulled the silver chain over her head and threw it away. "I do not want that thing!" she cried. "It is a counterfeit. My father lied when he gave it to me. I wish he had not lied."

"Peace, little one," soothed Eoin. "If he told you an untruth, it was for your benefit. That cannot be doubted. Be certain, moreover, that in all other ways he was honest with you. Jarred was a good man."

Having uttered these words, he suddenly averted his face. Violently, his shoulders began to shake. As he sobbed achingly beneath the lime trees, Jewel fetched the amulet from where it had fallen. She crept close to her step-uncle and dropped it in his lap.

"Here," she said softly. "You wear it. Perchance it contains some effectiveness, despite all."

"Nay," he replied in muffled tones, "I own an amulet, a good druid-sained one from the Sanctorum." He groped for the talisman he usually wore beneath his tunic, but it was no longer there. His fingertips traced across the nape of his neck, detecting a long weal, and it came to him that during the skirmish with the Marauder he had felt the chain bite into his flesh. It had snapped apart as his enemy ripped it off in an effort to garrote him.

"Well," he said, "it seems I do not have an amulet, after all."

Jewel looped the silver chain over his head and carefully cleared his bedraggled locks from his collar. "Now you will be safe from unseelie wights."

The child's kindness came near to undoing the man. "Gramercie," he whispered.

"Do not catch coneys this night, Uncle. Let us rest." She drew a corner of her traveling-cloak over both of them and, placing her head upon his shoulder, closed her eyes. Her lashes were fringes of sable silk against her creamy skin. Eoin dared not glance her way--she resembled Lilith so closely that if he looked upon her for more than an instant his heart began to decay like moldering stone, and his anguished spirit screamed its fury at the horror of his loss. Instead, he stared down at the amulet of bone. Another irony--thirteen years ago he would have given almost anything to possess this object. He surmised, now, it was a purely decorative trinket with no life-warding properties, no efficacy at all against malignant wights, but he did not care.

I am as good as dead already, he thought to himself, remembering the portent he had seen, the prediction of his own imminent death within the twelve-month.

He had been walking through the streets of Cathair Rua in the evening, leading his horse.

The street running alongside the Sanctorum was deserted save for a man in rags, picking about in a gutter. Spying a traveler with a horse, this beggar made ready to ask for money. As he approached Eoin, the deep, solemn pealing of a bell boomed out from a lofty belfry within the Sanctorum.

Forgetting his purpose, the beggar quickly looked up and made a sign to ward off evil. He grabbed Eoin's arm. "By the bones of Ádh," he said fearfully, " 'tis the passing-bell! I have never heard it ring at such a late hour! It's the bell they ring when someone dies. But there is no light in the belfry!" shrieked the beggar, gibbering with fear as he rounded a corner and disappeared from view.

The brass tongue in the bell's mouth made its voice say doom, doom, doom. Eoin counted the strokes. They ceased at thirty-seven. As the terminal vibrations thrummed away out over the city, Eoin realized the bell had numbered the years of his life....

When Eoin drew near a side-gate it sprang open and a strange child-size funeral procession emerged. On their shoulders they bore a small coffin, the lid of which was askew. "Ach, I've seen such wights aforetimes," the reappeared beggar spluttered startlingly in Eoin's ear. "Fear not. They're seelie enough if no man meddles with them."

"But this is impossible," muttered Eoin. "Wights are immortal. They do not truly die--yet this looks to be a funeral!"

The inquisitive beggar tapped the side of his nose knowledgeably. "It'll be one of their mockeries."

"Why do they do it?"

" 'Tis a death portent."

Nausea billowed through Eoin's belly.

"I want to see what lies in that coffin," he said impulsively. "Hold my horse for me and the job'll earn you sixpence."

"Give me the halter," mumbled the beggar. "But I warn you--those of their kind take offense if mortal folk try to speak to them. They might hurt you if you do."

Without reply Eoin threw him the rope halter and strode after the procession. As he came up with it he peered into the coffin. A shock bolted through him.

The figure lying there wore his own face.

The enormity of the portent sank in.

Heedless of the beggar's warning, he spoke to the coffin bearers in sick and quavering tones, saying, "When shall I die?"

They answered him not.

He overtook the leader, but when he reached forth his hand to touch him the entire procession immediately disappeared and a violent wind came barreling down the street.

The beggar dropped the halter and made off without his sixpence.

Under the lime trees, lying protectively beside Jewel in the wilderness, Eoin thought, I can only hope I will live long enough to see her safe to shelter.

"Where are we going?" Jewel asked next morning. After making a rudimentary breakfast they had refilled their water flasks at a freshet that tumbled from a crevice in the hillside, beneath the knotted roots of an overhanging linden tree. Now they set off downhill again, their boots rustling through sparse layers of leaves that lay like fragile seashells cast in copper, bronze, and red-gold.

The child had not asked that question before. In the last day or three she had begun to speak more frequently, but she never referred to the loss of her parents. Eoin understood she was still too stunned by the enormity of the disaster, too numbed to fully comprehend either the past or the possible future.

"Far from Slievmordhu," he replied, "to King's Winterbourne, the chiefest city of Narngalis. Warwick Wyverstone, sovereign of the north-kingdom, is a wise and just ruler, by all accounts. As you know, the foremost amongst his noble warriors, the famous Companions of the Cup, are as chivalrous and honorable as they are valorous. There is little or no love between Warwick Wyverstone of Narngalis and our King Maolmórdha Ó Maoldúin. We will keep your identity secret, but even if it were discovered, 'tis unlikely Narngalis would hand you over to Slievmordhu. King's Winterbourne is a most prosperous city. We shall find a place to stay, and I shall seek employment."

"I want to go back to the marsh," said Jewel. "Perhaps in a twelve-month or two it will be safe, and we can go then."

Eoin grunted noncommittally. He knew that as long as King Maolmórdha required a descendant of Jaravhor to unlock the Dome she could never return, yet he could not bring himself to shatter her hopes.

Farther away, through the spindly stems of larches, motes of snow seemed to be drifting. It was a flock of sulphur-crested cockatoos, so frostily pure-white they seemed unreal, as though shavings of highly polished platinum had been cast in handfuls on the wind. Above the heads of the wayfarers the woodland canopy hovered, shimmering in the breeze like an explosion of butterflies, jade and saffron.

"I have been thinking," said Jewel, marching along. "Is it possible the sparkly stone is the key to this precious Dome of Strang, rather than the sorcerer's only blood-relative?"

Eoin shrugged.

"If it is," she went on, "I would gladly give it to King Maolmórdha in exchange for the freedom to go home."

"Little one," said Eoin earnestly, "you are young and not yet learned in the ways of the world. Hearken. Maolmórdha is a weak man, despite that he rules over one of the Four Kingdoms of Tir. He dances to the tweakings of his druids, like a puppet on cords. The druids jealously guard their authority, their status and power. Do you think they would blithely allow a scion of Jaravhor to dwell freely in Slievmordhu? Janus Jaravhor was a mighty sorcerer, the most potent of his time, if the stories are true. When he died, the druids rejoiced. When no successor appeared, they were relieved. You are a child, but if they knew of your existence, I've no doubt they would wish to confine you--"

"But they cannot harm me!" argued Jewel. "I am close to invulnerable. My father told me so!"

"Let me finish! Although you are impervious to hurt, they might imprison you for life, in some forgotten dungeon. They would yearn to be rid of you before you reach maturity and come into your full strength, whatever that may be. Key or no key, 'tis you they would want."

"What full strength?" cried Jewel angrily. "My father wielded no gramarye! He was immune to injury, that is all. As I am, too, so it seems. But I have no special powers." She leveled her forefinger at a tall larch. "Fall!" she shouted. The tree stood unaffected, a bottle-green cone pointing up against the sky. Jewel stabbed her finger at a boulder, lichen-mottled, peeping from a filigree of wild sage. "Split!" she commanded. "Fly apart!" The rock remained unmoved, as it had for seven hundred and thirty-five years. "There, you see?" she declared, pouting. "I'd be no threat at all to the druids. They might as well leave me alone."

"Ah, but they would not. Their suspicious minds could never be certain of your innocuousness. And they are ruthless."

"Then I say, cursed be the druids," Jewel said with vehemence. "Here, Uncle," she added impulsively, "you take the stone." Having drawn the necklace over her head, she held it out to him. In her palm it glistened, as though she had torn a piece of radiance out of the sun. "I do not want it anymore."

Eoin pushed her hand away. "What are you saying?" he muttered incredulously. "It was your father's gift."

"Aye, but 'tis of no use to me. You, on the other hand--you have forsaken your house, your friends, your living, all just to go traipsing across the countryside looking after me. I owe you something in return."

"My breath and blood!" exclaimed Eoin, his features collapsing in mortification. "Oh, by my troth! Never say that, Jewel. Never say it. 'Tis I who am indebted to you. But do not ask me why, for I cannot endure to tell you."

Slowly she retracted her hand, yet she did not replace the chain about her neck.

"Anyway," said Eoin hastily, evading her inquisitive stare and hoping to put her mind at ease, "I own riches enough."

"All your coin and possessions remain back at the marsh."

"You are mistaken. I carry my good fortune with me."

"I cannot believe it."

"In sooth! Several years ago I did a good turn for some wights, and they rewarded me with luck in all my enterprises."

She was entranced. "Is it so? How did it come to pass?"

They forded a pebbly brook and started uphill again. As they plodded through the wiry grasses, Eoin told the tale of that night in the marsh when he had crossed an island, through groves of trees whose starlit boles were slender, silver dancers, shadow-haired. When he walked out upon a grassy, open space, a sense of strangeness had overtaken him.

An alarming racket had arisen on all sides. He knew he was amongst eldritch wights, although he could not see them, and he was afraid. Some were laughing; others were weeping. One of the wailing voices suddenly said, "A bairn is born and there's nowt to put on it!"

At this, Eoin jumped backward and sideways, for the voice had seemed to come from almost under his feet.

"A bairn is born and there's nowt to put on it!" squeaked the woeful voice a second time.

In the name of all good sense, what am I doing here? Eoin thought, in growing apprehension, out here alone with no one nigh for miles to hear my screams should any ill befall me....

"A bairn is born and there's nowt to put on it!" shrilled the melancholy voice again, but Eoin saw nothing except the gem-encrusted night sky, the dark grasses bending in the breeze, and the glint of starlight on black water. Swiftly unfastening two bronze shoulder-brooches, he doffed his cloak and cast it to the ground.

"Take this!" he croaked, his mouth dry with terror.

Instantly, the cloak was seized by an invisible hand. The howlings died away, but the sounds of mirth and celebration intensified. Hoping his action would content the wights, Eoin took his chance and fled.

"My action did indeed content them," he said, concluding his tale to Jewel. "From that night forward, I had great luck in gambling and trade."

"Why, that explains many things! How wonderful!" With that, the child slipped the chain of the white gem around her neck once again, and concealed it beneath her gown. "But--oh!" Abruptly, she halted.

Eoin stopped beside her.

"Won't your good luck cease now you've told of it?" Jewel said, frowning up at him, "That is the way with wights. It is astonishing you are not aware of it! Their gifts only remain as long as their source is not disclosed!" Her voice sank to a whisper and she darted furtive glances over her shoulders.

The marshman, however, knew exactly what he had done. Deliberately, perhaps as a kind of self-punishment, he had made known the origin of his luck and thereby surrendered it forever. In their mysterious way the wights would know what he had done, and instantly withdraw their endowment. Time past, the knowledge would have troubled him, but now it made him perversely glad. In his own view, he deserved to pay for his transgressions.

"Aye," he affirmed, giving a wry smile. He patted the child on the shoulder. "It never did me any good, being prosperous. I care naught if the eldritch gift is taken away."

"But you should not have told me your secret!" she protested, with irritation. "I hope no wights of eldritch overheard." Disconsolately she kicked out at a clump of red-capped toadstools sprouting near her toes. Her companion fancied he heard a burst of chatter, as of shrill voices, but he could not be sure. Perhaps it had been the twittering of small birds....

"Somehow, they will know," he said. "They always do."

Distraught, the child began to rail at him, but he soothed her, saying, "Hush, little one. Give a man leave to choose his own direction. Now, we must continue on our way if we are to reach shelter before our supplies run out."

Sulkily, she complied.

As they went on together he began to sing to her, to calm her. It was a song he had first invented when she was an infant, and he used to rock her in his arms:

"I'll make you a bonnet of a bluebell, silver shells for your shoon,

And me and baby will go dancing all by the light of the moon.

I'll make you a carriage of a pumpkin, white mice for the team,

And me and baby will go driving down by Watermill Stream.

I'll make you a song of pretty rose-buds, white and pink and gold,

And me and baby will be singing until the day is old.

I'll make you a necklace of bright raindrops falling one by one,

And me and baby will be laughing until the day is done.

I'll make you a cradle of a walnut, lined with down so light,

And little baby will lie sleeping, peaceful through the night."

Late in the afternoon a rain-shower blew away into the east and the sun, slipping through a gap in the clouds, flooded the western hillsides with amber radiance. Eoin and Jewel emerged from a straggling copse of linden trees. They had reached the other side of the Border Hills. At their feet, the ground sloped gently down. The trees opened out and they looked out over a vast windswept land striated with overlapping belts of trees, dark green, tinged with a dusting of topaz at the leaf-tips. Great draughts of fresh air swept up the rise, so intoxicating they took the breath away.

This was Canterbury Grasswood, an undulating region reaching from the Border Hills to Canterbury Water, the great river whose sources sprang amongst the mountain ranges of the east. Its rounded shoulders were lavishly clothed in grassland, scattered with open woodland. In places, the trees clustered closely together, forming dense patches of forest. Copper-beech proliferated here, and horse-chestnut, maple, elm, and elder. The northern horizon was veiled by a low band of mist rising from the distant river. Above the mist reared a line of peaks, the southernmost of the mountain ring that encircled and buttressed the distant High Plateau.

The wayfarers descended the final incline. It was a lonely spot, far from human habitation or the routes of Marauders, so Eoin decided to risk lighting a short-lived cook-fire. That evening he snared a rabbit, which they roasted for supper over the orange flames.

Seven days after leaving the Border Hills they were trudging, bound by their customary silence, along a footpath sunk between high banks of thyme, and overhung by elder trees gaudy with scarlet berries. The sky was overcast, and the wind had swung around, bringing a bitter chill down from the north. Instinctively, Jewel tugged her hood over her ears and pulled her fur-lined cloak more closely around her slight form.

"How do you know the way to King's Winterbourne?" she asked. "Have you been there?"

"I have not. Nonetheless, I know enough about Tir to be sure that if we head north we shall eventually arrive at the Canterbury Water, and if we veer somewhat east as we travel we shall find the bridge where the Mountain Road crosses the river. That bridge cannot be crossed without paying a toll to the watchmen of Narngalis."

"What if the watchmen suspect us?"

"We'll confront that predicament when we come to it."

"Can we not cross the river elsewhere, and avoid predicaments?"

"I know of no other way across the Canterbury Water, unless one journeys far upstream, or finds a ferryman, or goes far downstream to the bridges over the border in Grïmnørsland."

The sunken path dipped and ran rapidly downhill. At the bottom of a flowery dell a little wooden bridge spanned a stream. It was a rotting, rickety construction built on piles of moldering stone, the patched-up remnants of a more robust structure that had once spanned the watercourse. When they had reached the opposite bank the trail led them into a stand of maples and copper-beeches. Here Autumn flamed in its glory, splashing color far and near in vibrant shades of red, yellow, and orange.

"By all that's uncanny--what's that ahead?" Eoin said sharply. He thrust out his arm to bar the progress of Jewel, who was following behind him. They both halted, peering into the dappled shade that hung across the trail like a richly embroidered curtain. Something moved between the trees, then gathered shape to itself from contrast and dimness, from hue and saturated luminosity.

"It looks like a coach-horse," muttered Eoin.

"Which signifies it probably isn't one," Jewel hissed back.

A loud whinny emanated from the vicinity of the creature. It switched its ivory cascade of a tail back and forth, then trotted off up the path. As its palely glimmering form disappeared around a bend it nickered, rudely and brazenly.

Without thinking, Eoin clutched the amulet at his throat. "Sain us," he said. "Methinks 'tis a waterhorse! Who knows what kind it might be--a cabyll-ushtey, a shoopiltee, or a kelpie; an aughiski, maybe."

"Aye, but we are far from the marsh, and farther from the sea," said Jewel reasonably. "In which case 'tis unlikely to be any of those types."

"We crossed over a stream back there," Eoin reminded her. " 'Tis some sort of horse-wight, there's no denying, but whether 'tis seelie or not I cannot tell."

"We must go forward unafraid," Jewel decided. "Wights get power over mortals if we show fear. Besides, if it is a malevolent waterhorse, 'tis easy to avoid their clutches. All we must do is refuse to get on its back if it invites us."

"And be able to run very fast when it waxes wrathful at our refusal," Eoin murmured under his breath.

"Your blackthorn staff will help to ward it off," said Jewel optimistically. "What's more, you have knives of cold iron, and I picked a bunch of bright red elderberries this morning. We have your amulet of bone, and my gemstone for added protection. We can turn our clothes inside out, and we can whistle. If all else fails we can turn back and make for that stream. Once we cross running water we'll be safe for certain!"

"Very well." Eoin began to shrug off his pack.

"Oh," said Jewel, "but I shall be safe anyway. I forgot. Sometimes I overlook my own invulnerability."

"We shall both be safe," said Eoin, endeavoring to sound sincere.

They removed their outer garments, turned them seam-side-out, and put them on again. Whistling, they began to walk on, so filled with apprehension that they were unaware they were whistling two different tunes, that wove together in eerie discord.

Every time they rounded a twist in the narrow woodland path they would see the horse-thing again, poised as if waiting for them, whereupon it would flounce off as before, uttering clamorous and prolonged horse-noises. After they had gone on in this fashion for more than a hundred paces, the woods thinned, and when they came out into the open, the wight had vanished.

"I wonder what happened to the calf with the kerchief at its neck," said Jewel.

"Did you see that, too?" Eoin exclaimed. "I thought my eyes were playing tricks. First a coach-horse, next a calf with a horse's tail." Suddenly he turned around and slapped his thigh in a revelatory manner. "I wist I know what that wight was!" he said. " 'Twas a brag!"

"Are brags seelie?" Jewel wanted to know as they recommenced their journey at a somewhat swifter pace.

"Indeed," her step-uncle advised, "yet 'tis mischievous they are, as well. They are shape-shifters whose usual form is a horse, but not a horse associated with water. Like their cousins the phoukas, they are practical jokers who sport with humans for their own wayward delight."

"What is their custom?"

"Oh, the usual thing. They entice folk onto their backs and give them wild rides to bruise their seats and bemuse their wits, before flinging them into some duck pond or muddy puddle and galloping off, guffawing with laughter. Unlike the true waterhorses, they do not devour their victims. Brags can take certain other shapes, too. They may appear as a bushy-tailed calf with a white handkerchief tied around its neck, or as a naked, headless man. Once it appeared as four men holding up a white sheet..."

"Yes?" prompted Jewel.

". . . but that was when myself and three other fellows were trying to make fools of some of the marsh Watchmen," Eoin confessed.

"Did the trick work?"

"Not exactly."

Jewel smiled. At this rare sight, Eoin felt his heart must break.

"Do you know anything else about brags?" she inquired.

"A traveler's gest tells of a man who had a tailor make a set of garments for him, all in white. The first time he wore them, he met a brag, and ever since then whenever he wore the white clothes some ill-chance happened upon him."

"Then he was a fool to keep putting them on," remarked Jewel.

"That is the way of most folk," said Eoin, "ever hopeful that their luck will change. Moreover, he must have been a fearless man. It is told that he met the same brag a second time. All dressed in his white, he was returning from the naming ceremony of a nobleman's child. When he saw the brag in its horse-shape, he was undaunted. Probably longing for revenge, he leaped on the wight's back. They jogged on all right for a while, and he thought he'd get a good ride home, but when they came to the crossroads by the village green, the brag began to leap and arch its back so mightily that the fellow had all he could do to cling on. You may guess the outcome."

"It bucked him off into the middle of the duck pond and frolicked away, laughing like any mortal man?"

"Even so!"

Jewel smiled again, but it was a wan smile, and the dark smudges arcing beneath her eyes made her appear, to her step-uncle, like some waif.

By sunset, the wayfarers had not yet found a suitable place to make camp. They plodded on through the accumulating twilight, before settling at last at the margin of a thicket of elms, in the lee of a low embankment. There had been no sign of Marauders for many a mile, so it seemed safe to risk lighting a fire. Kindling was easily found. They had a good blaze crackling away when Eoin announced, "I'm off to catch something for supper." After a nod of acknowledgment from Jewel, who was busy reversing her cloak and hood to seam-side-in, he took the coils of snare-wire and fishing-line and slipped away into the dusk.

The wind had dropped. The evening was so still that the fulvous elm-leaves hung static. Hardly a one floated down to become part of the sumptuous mosaic on the woodland floor. Eoin backtracked until he reached a shallow ravine, whose steep walls he and the child had negotiated shortly before sunset. Roughly fifteen feet deep, it had been gouged from the sandy soil of the hillside by a bubbling beck that flowed along its nadir. To the marshman's eye, this had looked like a trout-stream. As he approached, the tinsel gurglings of moving water intensified. He had just let himself down the fern-decorated cliff-face when an awareness grew in him that the water's merry song was mingled with another sound. It was a soft, protracted cry, and the voice that made it was clear and melodious beyond human ability. Through the gloaming he discerned the silhouette of a woman. He stepped closer. When he saw her face, he felt a sky-bolt smite him. She was beautiful, but pallid as a marble tomb. A smoke of charcoal-hued hair tumbled down over her shoulders, and her eyes were two melts of the most vivid, concentrated blue he had ever seen in his life.

Lilith.

She made as if to speak to him, but gave voice merely to her weird wailing. Then, beckoning him to accompany her, she turned away. Eagerly he followed, until without warning, he was following nothing. Only moonlight stood in sky-high columns at the ends of the ravine, pleached with the first tendrils of a slowly elevating mist.

Tormented, he hurried back to the place where he had originally spied this vision, but there was no clue to her whereabouts. Forgetting the object of his excursion, he began to run wildly up and down the shores of the stream, calling the name that pounded through his head.

"Lilith!"

Much later, spent and gray-faced, he made his way back to the campsite empty-handed.

"What's amiss?" Jewel asked at once.

Having just witnessed a vision of the love of his life, whose death he had brought about, Eoin was shaken to the foundations of his being, shocked and utterly unmanned. "Naught," was all he would say, and he lay down as if to sleep, without taking so much as a bite of their meager fare.

Copyright © 2005 by Cecilia Dart-Thornton

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details