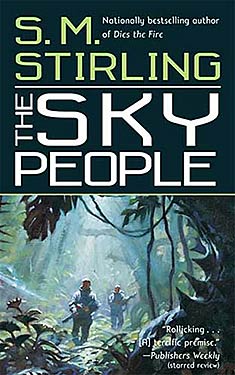

The Sky People

| Author: | S. M. Stirling |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2006 |

| Series: | The Lords of Creation: Book 1 |

|

1. The Sky People |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Marc Vitrac was born in Louisiana in the early 1960's, about the time the first interplanetary probes delivered the news that Mars and Venus were teeming with life--even human life. At that point, the "Space Race" became the central preoccupation of the great powers of the world.

Now, in 1988, Marc has been assigned to Jamestown, the US-Commonwealth base on Venus, near the great Venusian city of Kartahown. Set in a countryside swarming with sabertooths and dinosaurs, Jamestown is home to a small band of American and allied scientist-adventurers.

But there are flies in this ointment - and not only the Venusian dragonflies, with their yard-wide wings. The biologists studying Venus's life are puzzled by the way it not only resembles that on Earth, but is virtually identical to it. The EastBloc has its own base at Cosmograd, in the highlands to the south, and relations are frosty. And attractive young geologist Cynthia Whitlock seems impervious to Marc's Cajun charm.

Meanwhile, at the western end of the continent, Teesa of the Cloud Mountain People leads her tribe in a conflict with the Neanderthal-like beastmen who have seized her folk's sacred caves. Then an EastBloc shuttle crashes nearby, and the beastmen acquire new knowledge... and AK47's.

Jamestown sends its long-range blimp to rescue the downed EastBloc cosmonauts, little suspecting that the answer to the jungle planet's mysteries may lie there, among tribal conflicts and traces of a power that made Earth's vaunted science seem as primitive as the tribesfolk's blowguns. As if that weren't enough, there's an enemy agent on board the airship...

Extravagant and effervescent, The Sky People is alternate-history SF adventure at its best.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

Encyclopedia Britannica, 16th edition

University of Chicago Press, 1988

Venus--Parameters:

Orbit: 0.723 AU

Orbital period: 224.7 days

Rotation: 30hrs. 6min (retrograde)

Mass: 0.815 x Earth

Average density: 5.2 g/cc

Surface Gravity: 0.91 x Earth

Diameter: 7,520 miles (equatorial; 94.7% x Earth)

Surface: land 20%, water 80%

Atmospheric composition:

Nitrogen 76.2%

Oxygen 22.7%

Carbon Dioxide 0.088%

Trace elements: Argon, Neon, Helium, Krypton, Hydrogen.

Atmospheric Pressure: 17.7 psi average at sea level

Venus differs from Earth, its sister planet, primarily in its slightly smaller size and slightly lower average density, as well as the lack of a moon or satellite, and its retrograde (clockwise) rotation. The composition of the atmosphere is closely similar to that of Earth, the main differences being the higher percentage of oxygen and the somewhat greater mass and density of the atmosphere as a whole.

Average temperatures on Venus are roughly 10 degrees Celsius higher than those on earth, due to greater solar energy input, moderated by the reflective properties of the high cloud layer; isotope analysis suggests that these temperatures are similar to those on Earth in the Upper Cretaceous period, at which time Earth, like Venus today, had no polar ice caps.

Most of Venus' land area of approximately 40,000,000 sq. miles is concentrated in the Arctic supercontinent of Gagarin, roughly the size of Eurasia, and the Antarctic continent of Lobachevsky, approximately the size of Africa. Chains of islands constitute most of the remaining land surface, ranging in size from tiny atolls to nearly half a million square miles...

@@@

Venus, Gagarin Continent, Jamestown Extraterritorial Zone

1988

"Unnnngg-OOOK!"

One of the ceratopids in the spaceport draught team raised its beaked, boney head and bellowed, stunningly loud, as they were lead around to be hitched to the newly-arrived rocket plane. The supersonic-crack-of the upper stage's first pass over the dirt runways at high altitude had spooked them a little, but they were used to the size and heat of the orbiters by now.

Some of the new arrivals from Earth filing carefully down the gangway from the rocket plane's passenger door started a little at the cry. When one of giant reptiles cut loose it sounded a little like the world's largest parrot; the beasts were massive six-ton quadrupeds with columnar legs, eight feet at the shoulder and higher at their hips, twenty-five feet long from snout to the tip of the thick tail, and they had lungs and vocal cords to match their size. The long purple tongue within the beak worked as it called, and it shook its shield--the massive bony plate that sheathed its head and flared out behind to cover the neck. The shield was a deep bluish-gray, the pebbled hide green-brown above, with a stripe of yellow along the flanks marking off the finer cream-colored skin of the belly.

Then it added the rank musky scent of a massive dinosaurian dung-dump to the scorched ceramic of the orbital lander's heat-shield.

Welcome to Venus,-Marc Vitrac thought, as the score or so of new base personnel and the six spaceship crew gathered at the base of the ladder.-I'm glad it waited until the harness was hitched. That could have landed on my feet if it happened while we were getting things fastened.

He switched his heavy rifle so that it rested in the crook of his left arm--it was a scope-sighted bolt-action piece with a thumbhole stock and chambered for a heavy big-game round, 9x70mm magnum. Then he waved his right arm forward and called:

"Take it away, Sally!"

"Get going, you brainless lumps!" the slender ash-blond woman seated in a saddle high on the shoulders of the left-hand beast shouted

That was purely to relieve her feelings. Nobody really liked the dim-witted, bad-tempered dinosaurs, useful though they were. The joystick in her hand was the real control; she shoved it forward, and the unit relayed its signals to the receivers on each beast's forehead, hidden under hemispheres of tough plastic. That triggered current through the implants running down through skulls and into the motor ganglions and pleasure-pain centers of their tiny brains. The two ceratopids leaned into their harness, and the yard-thick hauling cable of braided dinosaur-hide came taut with a snap. After a moment's motionless straining the rocket stage lurched into motion and trundled down the long strip of reddish dirt towards the hangers and cranes where it would be mated with the big dart-shaped booster and made ready for its next lift to orbit.

It was a-lot-cheaper to ship electronic controller units from Earth than tractors and bulldozers, not to mention the nonexistent infrastructure of fuel and spare parts. All you needed to collect ceratopids was a heavy-duty trank gun, they'd eat anything that grew including the trunks of oak trees, and they lived indefinitely unless something killed them.

Marc wiped his face on the sleeve of his jacket as the rocket-plane left trailing dust, taking the radiant heat still throbbing out of its ceramic underbelly with it, and a stink of burnt kerosene. The coastal air of Gagarin flowed in instead, the iodine scent of the sea half a mile northwards, and smells of vegetation and animals not quite earthly. The sun was a little bigger in the sky than it would be on the third rock from the sun as well, partly because they-were-closer to it, and partly from the light white haze that never really cleared from the blue arch above. Otherwise apart from the weird fauna--and the size of the bugs--it might have been a spring day in California, in the seventies and fairly dry, yellow flowers studding a rolling plain of waist-high grass around them, just turning from rainy-season green to champagne color. Already some of the birds and fliers scared off by the rocket-plane's descent were winging back in. Something with iridescent blue-and-yellow feathers, a twelve-foot wingspan and a beak full of teeth screeched at him as it passed, snapping at dragonflies six inches across.

The little clump of new fish in their blue Aerospace Force overalls stood at the base of the wheeled gangway, woozy even in Venus' ninety-percent gravity after three months of zero-G despite all that exercise-en route-could do; at least they were used to the denser air and higher oxygen, since the passenger ships adjusted their own gradually on the trip. Some of them were looking a little stunned; others grinning ear to ear. He knew exactly what they were thinking, and his lips turned up as well--the thrill wasn't gone for him yet, not by a long shot:

Yeah, I've finally made it! All the tests and psych tests and physical tests and trials and qualifications and all the millions who started out on the selections and-I-was the one who made it!

Most of the-Carson's-six-person crew were here as well, looking a little more relieved than usual; there had been some sort of problem with the main fission reactor this time, just after the final insertion burn. The Aerospace Force kept two nuclear-boost ships on the run between Venus and Earth, the-Carson-and the-Susan Constant; there were three crews for each, one Earthside, one Venuside and one on duty. Rotating them through so that they spent two-thirds of their time on the dirt was good for their health, and even better for morale. Space travel was romantic in theory, but in practice it was very much like being on a submarine that never surfaced, with the added disadvantage of being a lot more dangerous.

The spaceship crew had all been here before, and they took the landing in stride. It was different with the new fish who'd be staying. One young black woman with civilian-specialist shoulder-flashes--she looked to be a couple of years short of Marc's twenty-five--bent down and gently touched the Venusian soil; when she straightened up a look of astonished delight was on her face. He met her eye and winked; he still felt that way himself, pretty often, and on-his-first day he'd gone down flat and kissed the dirt.

"Welcome to Venus generally and specifically, the Jamestown Extraterritorial Zone, folks! I'm Lieutenant Marc Vitrac, USASF, and one of the Ranger squad here, which means specimen-collector, liaison with the locals, and general dogsbody. We've got a howdah laid on. I know three months in zero-G makes you feel like a boiled noodle when you get back dirt-side."

A murmur of-no problem, feeling fine-and shaking of heads; you had to be nearly Olympic caliber physically as well as qualified in two or three degree-equivalents even to get onto the short list for Venus. All of them were probably proud of it, and they were all aggressive self-starters by definition. He shrugged mentally; he'd done exactly the same thing when he arrived, and had been puffing by the time he made it to the reception hall. The plain fact of the matter was that it took weeks to months of carefully phased acclimatizing before you got full function back. That was why they used the more expensive nuclear-rocket craft for shipping people between planets, instead of the cheap but slow solar-sail freighters. A big nuclear booster could get you here in a hundred and twenty days, give or take depending on orbital positions--the robot freighters took three or four times that long, and nobody could stand a year and a half without gravity, not to mention the risk of solar flares-en route.

Too much exertion right away could do lasting harm. This time they weren't taking any chances, and they'd be using something that usually carried groups on long-distance expeditions.

Instead of arguing he turned to the four spaceport laborers. "imiTaWok s'wee, tob,"-he said, in the tongue of Kartahown:-Get it back to the building, guys.

The locals grabbed the shamboo-framed wheeled staircase and began dragging it off after the rocket plane. The newcomers spared a few startled glances at them; you had to look fairly closely to see that they weren't common-or-garden variety Caucasoid earthlings, though the local-style sandals were the real giveaway. People around here tended to medium-tall height, olive coloring and mostly brown or black hair, with a minority of blonds and a smaller one of redheads; only the sharply triangular faces and hooked noses were even a little out of the ordinary. The four workers were shaved and barbered Terran-style and dressed in ordinary-for-Jamestown pants and shirt of parachute cloth; they couldn't be told from earthlings until they spoke. Put Marc Vitrac into an off-the-right-shoulder tunic, grow his hair long and tie it in a knot on the left side of his head, and give him a bronze sword, and he'd fit right in on this coast.

"Yeah, those guys are from Kartahown," he said, pointing east along the coast. The bronze-age city-state which was Venus' highest civilization was about forty miles thataway. "Some of them have picked up English, too, since they moved up this way looking for work."

Including some escaped slaves we're sheltering from people who'd like to beat them to death with bronze-tipped scourges, but let's not get into that right now.

"That's quick," one of the newcomers said; the oldest of them, in his mid-thirties and with a bird colonel's insignia. "We've only been here six years, and the base was pretty small for most of that period."

"Well, we're even more exotic and interesting to them than they are to us, sir," Vitrac said. "And by local standards, we're wizards and richer than God. A steel knife or a couple of yards of parachute fabric is real money here."

Plus we-don't-beat people to death with bronze-tipped scourges.

"And if you'll all follow me..."

He lead them off--slowly--across the cropped grass near the landing strip; there were two in an X shaped combination, each several thousand yards long. Another ceratopid stood waiting patiently; in fact, it was blissed out by a trickle charge to the pleasure center, drooling slightly onto the grass. A twenty-foot howdah rested on its back, made of laminated shamboo, with a shaped and padded underside and two broad leather girths running under the dinosaur's belly to hold it on. The seats were stepped like those in a movie theatre, to accommodate the slope of the animal's back from the high point over its hips. Marc stood by the short folding ladder at the right foreleg, once or twice discreetly helping a passenger with his free hand.

More than one gave the bigger-than-elephantine beast a dubious look; its steady breathing was a machine-like-whoosh... whoosh...-and the heavy reptile stink was strong, about like a neglected cage full of iguanas at a petshop. The massive columnar legs were taller than a big man, too...

When everyone was settled he folded up the ladder, put his foot on the ceratopid's knee, grabbed the edge of the bony shield and vaulted into the front seat to take up the controls. Once you got your muscle tone back the combination of lower gravity and extra oxygen made you hell on wheels physically--and they'd all been distinctly above-average specimens to begin with.

"Fasten your seatbelts, please," he said.

And keep your barf-bags handy. This thing sways like a sonofabitch.

Unlike many, he didn't bother to say-git-or equivalent, just pushed the control forward a notch and rotated the joystick. The beast gave a low coughing grunt and then a wince-inducing screech of complaint as it came out of a daze of quasi-reptilian ecstasy and turned in place before pacing forward; the weight of howdah and passengers wasn't really noticeable to something that weighed about as much as a big dump-truck, and everyone clutched the grab-bars. The strings of silver bells around the edges of the howdah chimed in chorus at the first lurch, then settled down into a-ting-ting-ting-ting-beneath the heavy thud of footfalls as the animal paced along; it wasn't doing more than walk, but each stride covered a lot of ground.

He did start a little as the black woman slid into the front seat beside him. He didn't think it was his own overwhelming attractiveness; he was a slim wiry man built like a gymnast or track-and-field star--which he'd been. He was also of medium height for Jamestown--five-ten--broad-shouldered, with a pleasant open face, olive skin and dark green eyes, his black hair cropped short. She just seemed exuberantly happy to be on Venus, and less returning-gravity-whipped by the voyage than most of the newcomers; and of course she was less constrained than someone in the Aerospace Force, although military formality was distinctly low-key here. For one thing, there was scarcely anyone below commissioned rank. A lieutenant was on the bottom of the heap.

She touched the plank of the seat, as if seeking reassurance in the rough, slightly splintery surface.

"I like the bells," she said.

"Me too," he replied; the silvery chiming was pleasant. "It's mostly to warn people out of the way, though. These things aren't what you'd call maneuverable, even Iced."

"Iced?"

"Ah, Jamestown slang. Internal Control Device; I-C-D, and so--iced."

"You've been here a while, right, lieutenant?" she said.

"Weh," he agreed cheerfully in the dialect of his childhood.

He was no more immune than most young men to attention from a good-looking woman; and on Venus you had the added pleasure of knowing she was in the top of the bell-curve for brains and general ability, too. He went on:

"More than a year now; Venus year, that is. Mostly in construction, maintenance, supply, but just recently we've had more time for real exploring and research--fascinating stuff. What we're learning is going to shake the earth. And a lieutenant is small potatoes here, ah, Miss--"

"Cynthia Whitlock, lieutenant..." she said, and held out a hand. "Sorry, I didn't catch your name--I was paying more attention to the surroundings than the spiel!"

"Marc Vitrac. Ethnology and linguistics, power systems and lighter-than-air pilot."

"Geology, minors in paleontology and information systems. And...-imiKartahownai 'n dus-jas?" she asked.

She had a pretty good accent, for someone working from recordings without being able to talk to native speakers. The hand that gripped his was firm and strong and dry, slender and long-fingered; shaking it meant he had to juggle the rifle he was holding in the crook of his other arm.

"Yeah, I've picked up a fair amount of Kartahownian. It's damned useful here; a lot of people along the coast speak it, sort of a lingua franca. Some of them have acquired a bit of English over in the town, too. They've got some very smart people there--it doesn't pay to underestimate them."

She tilted her head to one side. "Louisiana?" she said.

"Evangeline, eh, she was my-mawmaw," he said, exaggerating the Cajun lilt for a moment; he'd kept it deliberately, partly as a joke, partly as a gesture. "Bayou born and bred. Grand Isle."

"Harlem-born and bred," she replied, with only a trace of it in her General American.

Then her brows went up slightly as he took a quick glance skyward and started to raise the rifle. "Nope," he said, lowering the weapon. "He's not going for us. Guess we look too much like a 'saur."

When he'd relaxed she went on, indicating the rifle with a glance: "That-cannon-is a bird-gun?"

"Mais,-for those things,-weh, certainly," he said, turning a thumb upwards.

He was unsurprised she knew her way around firearms, even though she was a civilian; the selection program tended to pick intellectuals who were also outdoors types or vice versa. Then he raised his voice a little so the rest of the score of passengers could hear, and it took on a slight tour-guide tone. One that he realized was based on something he'd heard an uncle use when he did conducted tours of the bayous in his swamp-boats, throwing marshmallows to the quasi-tame gators for the tourists.

"Y'all might want to take a gander skyward. First big Quetza of the season and they're quite a sight."

Most of the passengers did look up. He heard gasps; it was one thing to watch video of a flying creature with a wingspan of eighty feet, but another to see one with your naked eye. Even back in the Cretaceous nothing even half that size could fly on Earth, but the gravity was a bit lower here, and the air was not only thicker but had more oxygen per unit to power flight-muscles. This Quetza was coming in low, coasting down from the inland cliffs where they nested, banking to avoid the built-up area of Jamestown and then sweeping back seaward.

The thin long-headed body was bigger than a man's and roughly the same shape, but it was tiny between the vast leathery expanses of wing that caught the thermals; the eyes in its long narrow beaked head were huge and yellow and it turned one of them towards the wagon as it went by overhead. Then the wings half-folded, and the great beast came down on the other side of the runways like an arching thunderbolt of brown hide and white-and-scarlet body-fuzz and yellow jaws. Those were slender, like a great pickax beak, balanced by a bony crest behind, and full of jagged teeth.

"Ah, shit, it's going for that herd of-churr, probably after a-bebette. Sorry people--I'm going to have to take a shot. Fire in the hole!"

It was the claws on the ends of the long legs that struck first, in a puff of dust. More dust fountained into the air as the giant wings flogged the air, and something struggled beneath as the thirty-odd adults and younglings in the herd spattered like water on a waxed floor, bawling and shrieking in terror. The week-old churr colt was the size of a medium pig except for the longer legs and it squealed like one. Churr were what the locals used as, roughly, horses; Venus didn't have any equivalent of the equines, as far as they knew. The shaggy social omnivores were actually more like a bear, and still more like a horse-sized dog crossed with a hog's digestive system.

The pterodactyl worked for height, looked down at the animal thrashing in its claws, and dropped it from two hundred feet. The squeal ran all the way down as the falling beast thrashed its legs, then cut off abruptly at the meaty-thud-of impact. The winged reptile turned in a circling gyre as it descended and then settled to the ground like a flying avalanche, mantling its wings over the dead animal as it fed. After an instant the long head came up with a dripping chunk in its jaws; it bolted the food whole, and you could see the lump traveling down the throat.

Marc brought the ceratopid around and pressed the bliss-out button to freeze it in place before he came up with one knee on the bench, taking a hitch of the rifle sling around his left elbow to give a three-point rest and working the bolt to chamber one of the heavy rounds; Cynthia slid down and went flat to peer over the edge of the howdah, her thumbs on her ears and mouth open. The pterodactyl's huge eye with its star-shaped pupil leaped into view through the sight; about nine hundred yards. Now shift a little for the wind,-stroke-the trigger...

CRACK!

Recoil punched into his shoulder despite the rubber pad and the weapon's muzzle brake and the fourteen-pound mass of the heavy rifle. Through the scope he had a brief glimpse of the predator's brain splashing away from the hollowpoint bullet. When he took the scope from his eye the forty-foot wings were thrashing the earth in a last frenzy; as they stilled to twitching the churr herd closed back in, standing in a circle for a moment before settling in to feed amid ripping and crunching sounds; the shaggy animals liked meat more than acorns or grass, though they'd eat anything at a pinch. They'd have it down to tatters and a skeleton by sunfall, with the corpse beetles' making sure not enough was left to smell by tomorrow.

This planet had an-active-ecosystem.

He worked the action and caught the empty shell as it ejected; that was one hundred and seventy-five dollars of the taxpayers' money in shipping costs, right there, and they had their own reloading shop now. The sharp acrid chemical stink of nitro powder hung in the air for a moment, then drifted away into the flowers-hay-hot-dirt-and-ocean smells.

"Jesus, lieutenant!" the bird colonel said reverently.

"Yeah, sir. You've got to watch out for the Quetzas, take a glance skyward every so often; the older ones like that can lift a grown man into the air with a high-speed snatch. They can't carry that much weight for long... but they don't have to. And you-don't-let kids go out without an armed escort! The First Fleet people shot a half-dozen daily around the town for a while and that seems to have taught them to avoid it. Lucky there aren't all that many of the really huge ones."

"They can learn?" the colonel said. "The reports say they're not very big-brained."

"About like a smart bird, say a parrot or a bald eagle--some of the smaller dinosaurian land predators are like that too. The herbivores like this one"--he kicked the ceratopid's shield "--are dumb as geckos. The big Quetzas migrate to the southern hemisphere in the winter, right down to the Antarctic continent, so you only have to worry about them from this time of year to the start of the fall rains. It's a good thing there aren't more of the thunder-lizards this far north, or it'd be impossible to live outside a cave."

The colonel nodded as Marc got their mount back into motion and headed into town. Then:

"What's that over there?" he said, pointing left and southward.

Everyone looked.-There-was a fifty-acre field densely planted with some reed-like crop about twelve feet high and thick as a woman's wrist, waving in the light breeze. The stems were a deep poplin green; the clusters of flowers on top were pink with white cores, and they attracted clusters of insects with coloring a lot like a Monarch butterfly, orange and black and yellow, except that they were palm-sized. There were millions of them, and they made a dense twirling blanket like a translucent Persian carpet over the blossoms. A strong scent half like cloves and half like cut grass came with the breeze, and an occasional fluttering winged drift of the insects.

"That's our shamboo crop--the local name for it has this goddamned click sound in the middle so we don't use it. When it's shoots just showing aboveground, it tastes like asparagus crossed with candy. Harvest it when it's four feet tall, and you can crush this sweet juice out of it and make sugar or a pretty good rum, and the Topsies--

"Topsies?" the colonel asked.

"Ceratopids ." He slapped the shield of their mount to show what he meant "--eat it like bonbons, that's what we use most of it for. At eight feet, it's too tough even for the big critters to like much, but you can get fiber out of it that makes dandy rope and burlap and canvas, and just recently we've made some paper from it. And when it's mature, the seeds taste a lot like sesame and give good oil for cooking and soap, and the stems are like bamboo only a lot stronger and tougher; that's what the howdah is made of."

He cleared his throat, sat and got their mount going again: "Jamestown proper is as you know closer to the water--"

That was because the first cargoes and personnel had come down in one-way capsules that landed on the shallow bay with its half-moon curve of blinding white beach; it had taken years to get the runway and orbital boosters ready for two-way traffic. The cargo-pods brought by the automated solar-sail craft that shuttled between the planets and Earth orbit on their long leisurely arcs still did splash down there, floating the last few thousand feet on parachutes whose cloth itself had a dozen uses here. There was a long wooden dock stretching out into the clear green water of the bay now; the weaker tides made things easier around a port. A native ship was tied up to it, a tubby fifty-footer with a mast and single square sail and twin steering-oars; a Grand Banks-style schooner rested on the other side of the wharf. White sails showed further out, where the water was purple-blue with small whitecaps.

He pointed out the other features of the settlement; the helium-cooled pebble-bed reactor and generator emitting a plume of steam beneath its mound of dirt, like a miniature version of the mass-produced types that generated most electricity back home these days; the airship mooring tower, built of shamboo and local woods--both the flying craft were out right now; and the semi-experimental fields growing crops from Earth alongside the Venusian plants domesticated by Kartahown. The town proper was low adobe buildings on either side of the three dirt streets. All were whitewashed and most had roofs that were curves of green synthetic, each made of half a cargo pod; a few used reddish home-made tile or brown wooden shingles instead. Workshops and laboratories vied with warehouse and residences; the houses had acre-sized walled gardens, and there was a small park and a fair number of big trees that looked a lot like live-oaks and had been standing here before the Terrans came.

Hitching posts and watering troughs stood at intervals along the streets, and there were board sidewalks on the main drag, with a proud but lonely stretch of brick in front of the town-hall-cum-commandant's-office. Riders on churr-back and pedestrians and carts drawn by churr or tharg-oxen made room for the ceratopid. There were a couple of engine-powered ground vehicles in town, but they were carefully mothballed for emergencies.

Many of the people waved and called greetings, and Marc waved back. This-was-a small town.

"Sort of an-acadaemogorsk-combined with frontier Deadwood," an English voice said from among the passengers.

Marc nodded, chuckling; he'd been a little surprised himself, when the final training courses had put so much emphasis on things like blacksmithing and carpentry, but it made sense when you remembered how far away Earth was and how much it cost to ship anything this far. Every ounce counted, and every ounce acquired on Venus meant spaceship cargo freed up for something that couldn't possibly be made here, like scientific instruments.

Even taken together there weren't all that many of the buildings yet, enough for three short streets; only one hundred thirty-two Earthlings were here, not counting the score of newcomers. And counting the twenty or so who'd been born here, and the nine who'd died. Nobody here was old, and everyone was a top physical specimen, but there was a whole planet of unfamiliar perils around them. About twice as many Kartahownians and tribesfolk lived around the base, and there was a floating population of visitors from there and elsewhere, traders and pilgrims and the sheerly curious. Marc went on:

"... and that's the chapel--the denominations use it on a rotating basis. And here's HQ," he concluded.

That was the largest of the buildings--three stories of adobe with the viga-beams that supported the floors poking through the whitewash, in an E-shape around courtyards, with a fountain and an arcade of treetrunks at the front. People bustle in and out, and traders squatted by blankets bearing their goods, everything from jewelry to colorful dyed cloth and cooking-spices.

He pulled the joystick back to the neutral position and pressed the-park-button that stimulated the animal's pleasure center; it put its head down and began to drool again. Ceratopids were too invincibly stupid to learn much, but they would stand still if it made them feel very good. That led him jump down from the driver's seat and put the ladder in place. A Hispanic woman in her early thirties appeared in the main doorway, waving a clipboard.

Marc gestured towards her: "Dr. Maria Feldman will give you all the standard familiarization lecture and assign quarters. I'm afraid we're very short-handed here, so I'll be leaving you in her capable hands."

"This way, people! This way!" she called.

The passengers began to file down. As they did he noticed one of them had slipped out and was handing Cynthia down from the foremost seat; he was a man of about Marc's own age, but two inches taller, blond, blue-eyed and handsome in a way both rugged and somehow smooth at the edges. He gave a toothy smile and squeezed hard as he shook hands. His eyes went a little wider as the Cajun squeezed back with carefully calculated force.

"Wing Commander Christopher Blair, RAF," the blond man said, in an excruciatingly Etonian voice; he was the one who'd compared the place to an EastBloc research settlement crossed with a frontier town. "Anthropology and linguistics; lighter-than-air pilot as well... as are you, I understand? Pleased to meet you, Lieutenant."

"The pleasure's mutual," Marc said, through slightly gritted teeth, surprised at the intensity of his sudden dislike.

Oh, well, they've all been together on the-Carson-for a quarter of a year,-he thought as he climbed back into the howdah and the two of them walked side-by-side into HQ, chatting easily.-I just liked her on first acquaintance...

In theory half the personnel here were supposed to be female. In practice it was hard to be precise about it with such a small population, and there was a slight but noticeable surplus of males, particularly among the younger, unmarried residents. It was annoying as hell and it meant that the single men among the Old Bulls had a built-in advantage.

He headed the ceratopid down towards the docks, shouting reminders to get out of the way occasionally when it looked as if the bells weren't enough--most of the rest of the traffic was pedestrians including the odd kid, or people riding churr, or churr-drawn wagons, and once a Kartahownian noble in a fancy gold-trimmed shamboo chariot, gawking around in his saffron tunic and gaudy barbaric jewelry, and gawking hardest of all at a 'saur doing what people told it to. He nearly gawked too long. A ceratopid just didn't stop, start or turn quickly...

It was a relief to turn right--eastward--towards the stables and storage and workshops out on the eastern edge of town; that was usually far enough that the stenches didn't bother people. The prevailing winds blew south-to-north here in the summer, and in from the ocean in winter; the business end of the settlement was also on the road, or dirt track, to Kartahown. And iced ceratopids didn't need much stabling; when you pressed the right button, it felt increasingly bad if it walked away from the fixed broadcaster, which kept them quiet even when their instincts said they should be migrating to the highlands for the summer. There were ditches, and fences made of a lattice of two-foot-thick treetrunks as backup, but privately he doubted they'd hold the beasts if the signal ever failed.

Real split-rail corrals confined the domestic-tharg-and churr they'd bought from the locals, and beyond them were tilled fields; a bustle of construction work was adding to the barns and storage sheds, and he caught a strong whiff from the steeping vats where mammal and dinosaur hide tanned. They could have bought everything from the Kartahownians, of course, but sacred Policy said otherwise.

OK, it's a fairly-smart-policy,-he thought. Relations with Kartahown's kings were good, but with the city as a whole were at best... 'Fraught' was the word he'd heard General Clarke use.-I'd be less grudging if it all didn't take up so much research time.

He turned draught-beast and howdah over to the staff, and slung his rifle across his back, and walked over to the slaughterhouse that also served as a processing point for specimens. It was cool inside, cool enough to dry his sweat and even raise a few goosebumps, courtesy of a wind-vent system. It didn't even smell too bad, since the blood-beetles took care of scraps--and of the meat, unless you took elaborate precautions. Dr. Samuel Feldman--doctor of paleontology and ethnology--was watching while a crew disassembled the hung-up carcasses of six-tharg-Marc and the other Rangers had shot for tonight's welcome-to-Venus barbeque, the giant wild variety that could weigh in at a ton and a half.

Feldman looked as much like a rumpled, absent-minded professor as it was possible for anyone who made the Jamestown selection to do. Mostly that meant he forgot to shave sometimes and never quite got around to growing a beard. His pants and pocketed shirt-jacket were the same as nearly everyone else and he had twenty-thirty vision, but somehow the lab coat and glasses were there as an intangible spiritual essence; for the rest he was a short, fairly stocky thirty-something man with dark curling hair and brown eyes and a round big-nosed face, and the body of a wickedly effective soccer goalie, which was exactly what he was in his off-hours.

"You know, dis ting is-definitely-a bovine," he said in purest Brooklyn--his first degree had been from NYU, followed by time at Stanford.

"Certainly tastes like beef. But come on, Doc. Billions of years of separate evolutions, here!"

It wasn't the first time they'd had this discussion; tharg was the commonest type of meat in the local diet after pork. Feldman prodded a finger towards the big animal whose flayed body hung head-down from a wooden hook over a big tub of oat-hulls.

"The anatomy is just too damned similar for a doubt."

"Mais, I think it looks a lot like a buffalo, me. Call it a bovinoid?"

"Or a tall, mean wisent," Feldman said, smiling. "But no, it's not 'Bovinoid'. Clade-bovidae, genus-bos. This thing is descended from the same ancestors as the ones we make brisket out of back home. It's even kosher--it divideth its hooves and cheweth the fucking cud!"

"It's a buffalo that can fly interplanetary distances? I know they're pretty flatulent when they've been eating those breadnut things, but not to escape velocity, I think."

Feldman's smile turned into a grin, then died. "Dammit, Marc, this is driving me nuts. What we need is a way to directly compare DNA... they're working on it, but it's going to be a while. Maybe we shouldn't have put all our R&D money into rocket science for the past thirty years. The serum immunology reactions, though... Dammit..."

Marc nodded; he didn't have the older man's terrier obsession, but it-was-something to worry at, and they'd come here for knowledge--officially.

And to make sure the EastBloc don't snaffle off a whole planet, and to taunt the Euros once again for following de Gaulle into a blind alley. I personally came because it was just so cool I couldn't bear to do anything else,-he acknowledged.-Still and all, the knowledge is cool too.

Everyone had expected wonders on Mars and Venus. Nobody had expected what they found. He ventured:

"Panspermia? Microbes on meteors?"

The scientist shook his head. "Not a prayer. OK, say life gets its start from complex molecules from space. We've-found-complex molecules in space that look like amino acids. That could get you something that's-generally-similar, starting with single-celled organisms in primordial oceans. Bugs on rocks, yeah, that would make things a bit-moregenerally similar, say in the structure of genes and chromosomes. But evolution's a chaotic process; you get general similarities, but not identities--hell, even on Earth, dolphins aren't fish and seals aren't dolphins and birds aren't bats. No-way-a couple billion years of random could reproduce, oh--"

He paused and caught a buzzing fly on the wing with the same smooth snap that he used to stop a soccer ball, then held it out in a cage of fingers, reciting in a sing-song tone:

"Two-winged flying insects with distinctive wing venation:-spurious vein-usually present between R and M; cells R5 and M1 closed, resulting in a vein that runs-parallel to posterior-margin of the wing; anal cell closed near wing margin. Hoverflies, to you. The only difference between this and Syrphid hoverflies on Earth is that it's as big as your little finger--and-that's-because the air here has a higher partial pressure of oxygen. You could get bugs here the size of Chihuahuas and I suspect in the warmer areas you do."

He released the insect and stopped the butchering of the tharg for a second to pry things open.

"Look at-that-and-that. Look at the structure of the shoulder joint! And the digestive tract's not just-grossly-similar, it's similar in-detail. It's not a different structure developed to do roughly the same thing, it's the same structure doing exactly the same thing, with only very minor differences. It's no more different from a Jersey cow than the cow is from a water-buffalo. It's a-ruminant, fer Chrissakes!"

"There's grass here too," Marc pointed out.

Feldman began to run his hands through his hair, then noticed the blood on them and poured a dipperful of water, wiping down on a coarse burlap sack hanging from a peg.

"Yeah. And that's way too similar to our grass."

"Mais, then the evidence would suggest that our theories of evolution are wrong," Marc argued. "Maybe separate evolutionary paths-can-reproduce fine details, at least when it gets the same initial conditions. Remember, evidence first, theory second."

Feldman glared at him balefully. "Yeah. But the facts are supposed to make-sense. We've got to get started on a good survey of the geological strata and fossil record for this planet. Bovines date back about twenty million years on Earth. If we could compare the fossils--"

"Collected by all one hundred forty-six of us?" Marc said reasonably, and grinned inwardly as the paleontologist kicked the hanging carcass with concentrated venom. "Of course, maybe the God-did-it crowd are right--"

"Them!"

Feldman started swearing; when he switched to Yiddish Marc had to fight to keep the grin inward.

He's a good boss, him, but sometimes I just can't resist.

@@@

Venus, EastBloc Station Kusnetsov

Low Venus Orbit

The upper stage of the EastBloc shuttle-Riga-was an elongated wedge with two vertical stabilizers at the rear. Its rocket engines were strictly for the ascent to orbit, when its first stage carried it to twenty-five thousand meters and Mach 3; it was designed to dead-stick to a landing, using its belly as the heat-shield and lifting body. Captain-pilot Franziskus Binkis floated in through the docking tunnel that clamped to the lower spindle of the wheel-and-axle configuration of the station and sighed in relief as he deftly dogged the hatch and then pushed himself down to strap into the central pilot's station. There wasn't really any difference in the stale recycled taste of the dry air with its tang of ozone, since the Riga had been docked here for three days, but his lungs and nose insisted it felt more alive.

His eyes skipped over gages and readouts; most were old-fashioned analogue devices, it being resentfully accepted that the-Ami-were ahead in plasma-screen technology, even with the latest Chinese improvements; officially digital readouts and touchscreens were regarded as unnecessary luxuries. Li was ready at the engineer's console, and Nininze in the copilot's seat.

"Glad to get the cargo stowed," the Georgian said. "It must be important, not to be sent down with a cargo pod to Cosmograd. I wonder what it is?"

The pilot grunted. It-was-important, which was exactly why Nininze shouldn't have asked that question. The Georgian was short, dark, lively, and talkative--exactly what a Georgian was supposed to be like. Binkis was an equally archetypical Lithuanian in looks, tall and ash-blond with pale gray eyes, but unlike the stereotype he was also close-mouthed. Li was from Canton, and doll-pretty; she was also even more silent than the pilot, except where her machinery was concerned, and he was fairly sure she reported to Base Security.

"Part of it is computer parts," Binkis said. "Let's get the checklist completed."

Li and Nininze nodded with a chorus of-Yes, Captain.-The-comrade-was best left off these days except on formal occasions; otherwise you were likely to be suspected of left-deviationist hankerings for the old days, which wouldn't do your career any good. A sensible man kept up with the changes.

"Poor Alexi," Nininze said, after they finished the run-through on the maneuvering jets. "Three more weeks up here, and not even any brandy!"

Binkis grinned silently as he watched Li finish the checklist on the navigational computer. He happened to know that a friend on the last visit of the nuclear-boost shipZuhkov-had left several bottles of quite good Stolychina with Alexi in return for a small stuffed pterodactyl, priceless on the black market back home if you could get it past the inspectors, or cut one of them in on the deal. Anyone who thought they could forbid liquor traffic in an organization founded by Russians was crazy. That didn't stop Security from trying, of course, and even trying to prevent people from making their own untaxed hooch down planetside, which showed you how in touch with reality-they-were. Of course, the current Security chief was a German named Bergman, with a spring-steel poker up his arse.

He'd been a compromise, when the Chinese wouldn't accept a Russian and the Russians baulked at having the commandant-and-the police general Chinese.

"Cosmograd Control, this is Riga-alpha, reporting all systems functional for descent," Binkis said.

On the second try the message went through. Venus had a turbulent atmosphere with a great deal of radio noise; it made long-distance communications awkward. He used Russian, which was still the common language of the EastBloc space service.

He'd also meticulously checked everything twice, most particularly the parts that were the Station chief's responsibilities.

Alexi is a good man to have a drink with, but at seventh and last, he is a Russian, and thinks machinery will perform if you give it a good kick. A Russian is a Mongol with blue eyes--halfway to a black-arse.

There was the odd token Tadjik or Uzbeck, but the core of the program was still Slav, with a fair sprinkling of minor Soviet nationalities--Balts like him, people from the Caucasus like Nininze--plus plenty from the other Warsaw Pact countries... and an ever-increasing percentage of Chinese. It was all supposed to show true internationalism at work. He liked the Chinese more than the Russians, on the whole; they were better at detail work, and they took the new regulations on private initiative to heart rather than grumbling at them. Since a couple of them started restaurants in their spare time you could finally get a decent meal in Cosmograd that you didn't cook yourself, and it was also now possible to get a broken light replaced without waiting through three weeks of surly excuses.

The accented voice of the Hungarian duty officer groundside crackled through the speakers: "Cosmograd Control here. You are cleared for landing, Captain Binkis. Transmitting code."

"Spacebo," Binkis said

For a moment he looked at the great mottled disk of Venus through the windows, thick white cloud-masses and thinner upper-level haze and streaks of blue below.-Coming home, Jadviga,-he thought, and punched the-execute-button.

A loud-clunk-sounded from above as the docking collar disengaged. They were already weightless, but there was a peculiar feeling in the inner ear as the big gyroscopes whined and twisted the nose of the-Riga-to the proper alignment.

"Commence--" he began. Then a startled obscenity: "Pisau!"

The ripple of action on the dials showed the firing sequence for the retrorockets! "Li, override that!"

The Chinese woman's hands danced on the flight control consol. "Negative, Captain," she said tonelessly. "The flight computer is not responding."

Binkis slapped the main manual override switch; he couldn't do a reentry burn by hand, but he could stop it until they'd figured out what went wrong. Nothing... and then the huge impalpable hand slamming him back into his seat as the retrorockets blasted, and the view ahead vanished in a haze of burning gas.

Trilinkas sau ant kelio triesk!-he screamed mentally at the useless controls.-Fold yourself in three and shit!

Then with an effort that made sweat break out on his forehead: "Li, see what trajectory this puts us on."

For as the rockets killed some of its orbital velocity, the-Riga-began to fall.

Copyright © 2006 by S. M. Stirling

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details