Added By: illegible_scribble

Last Updated: SSSimon

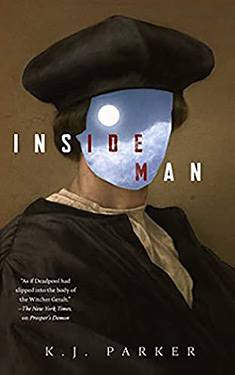

Inside Man

| Author: | K. J. Parker |

| Publisher: |

Tor.com Publishing, 2021 |

| Series: | The Empire: Prosper's Demon: Book 2 |

|

1. Prosper's Demon |

|

| Book Type: | Novella |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Alternate History (Fantasy) Historical Fantasy |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

An anonymous representative of the Devil, once a high-ranking Duke of Hell and now a committed underachiever, has spent the last forever of an eternity leading a perfectly tedious existence distracting monks from their liturgical devotions. It's interminable, but he prefers it that way, now that he's been officially designated by Downstairs as "fragile." No, he won't elaborate.

All that changes when he finds himself ensnared, along with a sadistic exorcist, in a labyrinthine plot to subvert the very nature of Good and Evil. In such a circumstance, sympathy for the Devil is practically inevitable.

Excerpt

Better the devil you know, so allow me to introduce myself: I'm the Devil. Or at least, I'm his duly accredited proxy and representative, part of his organization, part of him in a deeply spiritual sense, flesh of his incorporeal flesh, spirit of his profoundly antisocial spirit. I do little jobs for him (actually, properly speaking, for them; he's a body corporate, like a swarm of flies--see under "My name is Legion: for we are many"), such as occasional tempting, a bit of general legwork, but mostly bread-and-butter demonic possession. In that capacity, I'm your worst nightmare, the most horrible thing that can possibly happen to you in this world or the next. You couldn't bear to look me in the face, something the sun and I have in common, but let's not go there quite yet. You really don't want me inside your head; trust me on this if on nothing else. It may therefore come as a bit of a surprise to you to learn that I'm basically on your side, or at least that we're ultimately singing from the same hymn sheet, you and I.

Suppose the hand dislikes the ear, and the ankle despises the shoulder blade, and the appendix thinks the colon is full of it. Would it matter, so long as they all obey the brain and believe in what it's trying to do? Maybe the rain hates the sea--I don't know. They all have something in common. We all do, even you and me. I like to think that what we have in common is what's right.

Other people, however, don't necessarily share our view.

***

My current assignment is about as far down the prestige list as you can get without dropping off the bottom of the page, but it suits me just fine. Actually, it's difficult, demanding work, calling for intelligence, patience, resourcefulness, and--how shall I put it?--a certain refinement and sensitivity that many of my colleagues, admirable officers in so many respects, lack.

I do liturgical compliance at the Third Horn monastery. Nice place; I like it there. I particularly love the west cloister. It's got an exquisite herb garden in the middle, with a small fountain that catches the midday sun. The chapel, which is bigger than most cathedrals, is early Reformed Mannerist, with a stunning rose window as you come in the south door and a forest of dead straight red marble pillars shooting up fifty feet and then blossoming into the most amazing traceries, like fingers spread to support a gossamer sky. Maybe the Brothers were a bit too lavish with the goldleaf here and there--in ecclesiastical interior design, there's a wafer-thin no-man's-land between pious zeal and vulgarity, but they neglected to tell the Mannerists that; the overall effect is nevertheless pleasing to the metaphorical eye and soothing to the nerves. In the Third Horn chapel, I feel at home. I feel safe.

Liturgical compliance monitoring--LitComMon as they call it at Divisional HQ, though I really wish they wouldn't--is more of an art than a skill, if you ask me. A thousand years ago, the Third Horn was endowed by Duke Sighvat III to sing masses for his soul in perpetuity, in shifts, round the clock; the idea being that if you can afford to pay Holy Mother Church a very large sum of money, then once you're dead, a continuous, unbroken chorus of prayer will rise up from the exceptionally pious monks of the Third Horn, imploring divine mercy for your soul for ever and ever. The logic is irresistible. No matter that when you were alive, you were as evil as a barrel full of rats and that you died in your sins, entirely unrepentant. The Third Horn monks, the very best saints that money can buy, are men of such irreproachable sanctity that He can deny them nothing; therefore, you are forgiven for their sakes, not your own. It's a sweet deal at a sensible price. Say I sent you.

Which is where I come in; that is, me or someone else pulling light duty on account of fragility, incompetence, or being someone's metaphorical brother-in-law. The monks offer up prayers for the dead twenty-four seven, using precisely calculated forms of liturgy of known and proven effectiveness, the same formulae over and over again, like lawyers conveying a free hold, while unending ages run. My job is to sidle up to a choir monk in full flow; slip in through his ear, eye socket, or open mouth; and distract him, insinuating into his mind an irrelevant, mundane thought, sapping his concentration so that he mumbles, lets the stress fall on the wrong syllable, gets a word wrong or in the wrong order, maybe misses out a whole phrase. That, naturally, invalidates the whole prayer--those who live by the letter of the law die by the letter of the law, and you can't have it both ways--and the soul of some evil rich bastard has a nasty five minutes in the blissful Hereafter, until the next cycle of prayer starts and he's safely enveloped once again in protective intercession.

There's more to it, actually, than meets the metaphorical eye. The Third Horn boys are hardened professionals, carefully selected and highly trained. You can forget trying to interest them in images of naked women and wild debauchery, or anything so crude as that. Your rustic provincial monk can usually be distracted by resentful thoughts about his colleagues--why does he always get to carry the thurible at vespers on the third Tuesday in Annunciation, it's so unfair--but try that on a Third Horner, and he'll laugh in your metaphorical face. The usual approach adopted by my colleagues, and standard operating procedure in the field operations manual, is to seek to undermine the citadel of faith with the saps and petards of doubt--as the Brother repeats the same mantra for the twentieth time that morning, you whisper in his ear, What does this actually mean? Does it mean anything? Come on, admit it--you're wasting your time, and all of this is futile.

We have our established procedures, time-honored and enshrined in the Book of Rules. They don't work, but we have them and we carry on trying them, because our orders tell us to. In my experience, doubt glides off the case-hardened faith of a Third Horn monk like water off oilcloth; one of us is wasting his time in a futile act of faith, but it's not the monk--it's me. So I have my own approach, which from time to time actually works. Normally wild horses wouldn't drag the secret out of me, but what the heck.

The way I do it is this: Forget the naked floozies, the resentful thoughts, the nagging doubts. You're playing to the other guy's strengths, and you'll lose. No, go for him where he's vulnerable. So, when he's locked in prayer, concentrating on his devotions with every fiber of his being, I offer him a fleeting glimpse of the transcendent. I share with him--just for a split second--my own memories of what it was like before the Unfortunate Event. For a fraction of a heartbeat, he stands where I once stood, bathed in the glorious light of the Word, on the right hand of the eternal throne, looking up into the face of the Everlasting and seeing reflected there--

Yes, I know. It's a rotten trick to play on anyone, let alone a holy man, but sometimes it works, and all's fair in good and evil. The better the monk, the more successful it's likely to be, and I maintain that everyone's a winner: he gets a moment of transcendent revelation, I get ten points for distracting his attention, the evil sinner in the Hereafter gets a timely reminder of what he paid all that money for--and what excellent value he usually gets for it, except when I happen to be on the job.

Well, not everyone. I get my ten points, but in order to share the memory, I have to reopen it. That's rather a high price to pay for ten points. So, some of the time I'm a conscientious officer and do my duty to the best of my ability, even though it's agonizingly painful, and some of the time I'm a conscientious officer and do my duty the way I'm supposed to, according to the procedure set out in the field operations manual, even though it doesn't work. I'm only obeying orders, after all.

So there we are, me and Brother Eusebius, who's basically all right in my book. He's seventy-six years old, joined the order as a novice when he was nine; as of compline today, he's recited the mass for the dead 142,773 times. There's a thing called muscle memory. It's how archers and swordsmen and athletes train. You do something often enough, your body can do it perfectly even when your mind is miles away. The muscles that control Brother Eusebius's tongue and larynx run as smoothly and efficiently as the great mechanical clock in the Third Horn bell tower: word perfect, unflappable, automatic. His mind is away with me, gazing into the ineffable light of His presence, but his lips are still shaping the magic words, in exactly the right order, with the stresses in exactly the right places. I enjoy a challenge, but this guy's got me beaten. Ah well. Tomorrow is another day, and tomorrow and tomorrow. No big deal. Light duty.

***

I'm on light duty because I'm officially fragile. That's the new buzzword at Division. It means you had a bad experience at some point that left you no bloody use to anybody. You spend a lot of time sitting in complete darkness, people have to repeat things several times before you reply, and unexpected loud noises or someone asking you to pass the mustard is likely to reduce you to floods of hysterical tears. Not your fault you can't help it, your record shows that you were once a brave and reliable officer with a bright future ahead of you in Applied Evil, but that was then and this is now and we have a department to run. You're still on the books, and something has to be found for you to do. This theoretically counts as work, and if you fuck it up, nobody will know or care. Have at it, therefore. Cry "Havoc!" and let slip the squirrels of war.

Absolutely. I had a bad experience once. I prefer not to talk about it, if you don't mind.

***

Brother Eusebius comes off shift in the early hours of the morning and heads for the refectory, where I'm waiting for him with sesame-seed rolls and mulled wine. They believe in austerity at the Third Horn, in the same way that they believe in the Sashan Empire: it's real and it's in all the books, but nothing to do with us. A quarter to three, and no one in the place but him and me, definitely an opportunity worth following up. Brother Eusebius is a good man, but he has an inquiring mind, and what he's been seeing lately makes him wonder--

He sees me inside a deacon from Odryssa visiting the Third Horn library to consult a commentary on Theodosius. There's always one or two new faces in a big, cosmopolitan monastery like the Third Horn; it's one of the things he and I both like about the place. I happen to know, having been inside his mind earlier, that he's rather fond of sesame-seed rolls,whichiswhyIcreptinto Brother Cellarer's head and planted there the notion of baking them today. Some people might call it demonic possession, but to me, it's just being considerate.

Brother Eusebius nibbles the end off his rolland looks at me over it. "Not bad."

"Personally," I reply, "I could do without the hint of cinnamon."

"Me, too, but nothing's ever perfect. Thank you."

Oh. "What for?"

He smiles at me. "Sometimes, to win us to our harm," he says with his mouth full, "the instruments of darkness bring us buns. Not that I'm complaining, mind you."

I think something uncouth, under my breath. "How did you know?"

"Oh, come on," he says, not unkindly. "I've been a monk here for sixty-seven years. I can spot one of your lot a mile off."

And that's me told. I sigh.

"Don't beat yourself up about it," he says. He's a short man with dark skin, white hair, and pale brown eyes. "Actually, you're not bad--you'd fool most of the pinheads we get in the profession these days." He nibbles a bit more of his bun. "Was that you inside my head earlier?"

I nod. "Sorry about that."

"No, please, don't apologize." He leans forward a little. "I've got to ask. Was that--real?"

"Excuse me?"

"What you showed me." There's a certain urgency in his voice, just a faint pink tinge of blood in the water. "Was that--?"

"My memory," I say. "Yes. Unaltered and unredacted, for what it's worth."

"Really real?"

"Do you honestly think I could make something like that up? Besides, there's rules about that sort of thing."

"Rules? Honestly?"

"A code of conduct. So, yes, that's a genuine memory. From before the--"

"Yes, of course." He's anxious to spare me the embarrassment, bless him. "So there really is a--?"

"Yes."

"Ah." He looks at me, his eyes shining. "And He--?"

"Exists, yes." Pause. "I thought you knew that."

"Believed," he says softly. "As opposed to knowing. There's a difference."

"I suppose so," I say. "Well, then. And now you know."

"As opposed to believing." He frowns slightly. "Rather an extraordinary position to be in, for someone in my line of work. Being sure, I mean."

That makes me smile. "You've always believed, though."

"Oh, definitely." He's telling the truth. "Never a moment's doubt in seventy years."

"Does knowing--spoil it?"

"Not exactly," he says after a moment's thought. "It makes a difference, definitely."

"But in a good way."

"On balance, I think so, yes."

"Glad to have been able to help."

He looks at me. "Are you?"

I shrug. "He exists," I say. "Where I come from, that's not exactly a state secret. It's you people who make everything so complicated."

"Ah. Well, in that case, thank you."

"My pleasure. Sometimes one has to be kind to be cruel, after all." Pause. "I hesitate to mention it, but a small token in return--"

He looks up sharply. "I'm not sure about that."

"Oh, go on." My most charming smile. "It's not much to ask. A misplaced pronoun or a slurred consonant, that's all--just enough to make the blessed Sighvat choke on his sherbet. A momentary lapse in concentration, and next time after that, you do it perfectly. It's not going to kill anybody."

"Doing deals with the--"

"It's not a deal," I point out, "since you've already received the benefit, free, gratis, and for nothing. Therefore, there would be no--"

"Collusion?"

"I believe the correct legal jargon is consideration. No bargain. Just a graceful gesture of thanks on your part. Call it a professional courtesy, from one old lag to another."

"I don't know." He looks at me.

I sigh. "It's one of those cases," I say, "where the order of events is of the essence. If I came to you and said, 'Snafu the mass for the dead, and in return I'll show you the face of the living God,' then, yes, that would be actionable and we'd have you for it. But where there's no reciprocity, and no ongoing obligation--"

"Moral obligation."

"Moral obligation to one of our lot? Oh please."

He grins. "It would be a sin."

"True," I say. "But a forgivable one."

"If you do the sin with the intention of repenting later, the repentance doesn't count."

"Tell you what," I say, "I'll pray for you. How would that be?"

"Try one of these rolls," he says. "They're really very good."

If at first you don't succeed--"I met him," I say. "Once."

"Sorry, who?"

"Sighvat the Third," I tell him. "The evil little shit you spend your life praying for."

"Ah. Him."

"Yes. Would you like me to tell you about him? Some of the stuff he did?"

"Not particularly, no."

"I wouldn't say we were exactly close, Sighvat and me," I go on, "but I knew him quite well. Very well. Inside out, you might say."

"Ah."

"I was in his mind," I continue, though I don't like making Brother Eusebius feel uncomfortable. "Deep inside his head."

Eusebius nods slowly. "What was it like?"

"To coin a phrase, furnished accommodation. Everything I could possibly want was right there already, waiting for me."

"I see."

"And that's the man who," I say, "thanks to your ceaseless intercession, reclines at ease in the company of the blessed elect. Actually, I'm surprised he wants to. Fish out of water, if you follow me. He must get dreadfully lonely."

"They do say, hell for company." He frowns. "His money endowed the monastery, which for a thousand years has been feeding and clothing the hungry and homeless, educating the children of the poor, healing the sick, preserving the text of the scriptures--"

"'The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.' Only arse about face, in this instance. Quite. It would only be a very brief interruption. No permanent harm done."

He looks me in the eye. I don't blink. "Not to him."

I sigh. "Fine," I say. "You win. Though in all fairness, I should point out that ingratitude is also a sin."

"Nobody's perfect." He grins. "I'll pray for you if you like."

"Thanks," I say, "but I have an idea I'm a bit above your prayer grade. No offense."

"None taken. And it's the thought that counts."

"No," I tell him. "It isn't."

No rest for the wicked, so I disembody and trudge back to the chapel to try my luck with Brother Hildebrand on the day shift. Hildebrand was a mercenary soldier for twenty-six years before he heard the call--faith like concrete but not the sharpest knife in the drawer, theologically speaking. Unfortunately--

"Hello," says my old comrade in arms. "What are you doing here?"

"Lofty?"

"Keep your voice down," Lofty hisses, loud enough to wake the quick and the dead. "He'll hear you."

Lofty's not his real name, of course. It's just a nickname, something I call him because it annoys him. Why he finds it so annoying, neither of us can remember. He's exactly the same age as me, to the nanosecond, and we've been getting on each other's nerves and under each other's feet for all Time.

"Sorry," I say. "I didn't realize."

"That's perfectly all right," Lofty says. "Not a problem. And if sixteen years of slow, patient work goes gurgling down the pipes just because you happen to come crashing in, shouting the odds at the top of your voice, so fucking what? I can always go back to square one and start over again."

I never liked him much, even before the Fall. I have a shrewd suspicion he doesn't like me either. "Has it really been sixteen years?" I ask him. "Good heavens. Seems like it was only yesterday--"

"Go away."

"My pleasure," I say truthfully.

***

Sixteen years, what we in the trade call a sleeper job. A speciality of mine, as it happens, before I got fragile. Typically, a sleeper is someone identified at a very early stage as being useful to the Plan. He might have certain qualities of mind, soul, or body, or a destiny that'll put him in exactly the right place at the right time.

I once spent eleven years in the mind of a poor widow who sold cabbages out back of the Poverty & Justice, at the Hippodrome end of Brook Street, just before the war. She was nobody: nobody's wife, nobody's daughter, nobody's mother, nobody's reliable tenant or valued employee. Nobody would ever miss her, take any notice if she started acting funny--or funnier than she usually did, poor addled creature. Even if I got rumbled, nobody would pay good money to have her put right, because that's work for highly trained specialists, and their services are expensive. Seen as too ugly and too dumb to be worth exploiting. (I don't think I'd want to be a human, somehow; you people never seem to have got the knack of looking out for each other.) She wasn't worth anything to anybody, except me.

Eleven years, and she never once suspected I was there. But on a certain day in June AUC 1171, she took a knife, hid it up her sleeve, joined the crowd outside the GoldenSpire temple justas the Grand Duke was coming out after Mass, and stabbed him three times in the neck before anyone could stop her. Which she wouldn't have done if I hadn't been deep in her head all that time, twisting her mind and rubbing memories into her wounds, lovingly nurturing her resentments and warping her perspectives to the point where what she did was simply inevitable. And that, boys and girls, is what caused the First Social War (sixty million dead, if you add in the famine victims), proof if any were needed that sleepers really do work, and I don't give a damn what the bean counters at Division say about inappropriate use of resources.

The only thing I'd be inclined to question was assigning Lofty to sleeper duty. It calls for certain qualities, not least among them patience, resolve, a cool head, the ability to think on your feet--Don't get me wrong, he's a good officer in his way. I know of nobody better at draining every last scrap and scruple of joy out of life, flooding minds with black despair, shattering faith, dispelling hope--good, basic, bread-and-butter stuff like that. But finesse? Do me a favor. The proverbial bull in a china shop. The sort who'd trip over something in the middle of the desert.

"Perfectly true," says Divisional Command when I raise the issue. "He's a clown. Solid marble from the neck up and two left feet. Trouble is, who else have we got right now?" He looks at me.

I look away.

(Did I mention the slight difference of opinion between Area and Division, on the subject of my fragility? Area maintains that I'm a basket case and should never work on anything Grade 3 or above ever again. Division takes the view that I used to be a basket-case but I've had a long time to get better, and they're the ones who have to find the manpower for all the wizard schemes Area comes up with, and the talent pool isn't exactly infinite. I must confess, I'm with Area on this one. Of course, my feelings on the matter count for absolutely nothing at all.)

"Is this something I need to know about?" I ask.

"You? Heavens, no." He looks at me as though he's just bitten into an apple in a garden and found me there."This is big stuff, and everybody knows you don't fancy it anymore."

Nitric acid off a duck's back. "Only," I observe,"Lofty's got a point. I could've ruined everything, blundering in not knowing it was a sleeper operation. If you want me to back off from the Third Horn, just say the word, and I'll go somewhere else."

He's got that harassed look I know so well. "What I want from you," he says, "is to carry on doing the job you were assigned to do and leave the long-term strategic planning to us. Just mind where you're putting your great big feet, that's all."

"Nothing would give me greater pleasure," I say gravely. "But it's no use saying don't go treading on the mines if I haven't got a map of the minefield."

I'm doing it on purpose, and both of us know it. I used to tease him back when he was just a snot-nosed junior executive officer and I was his superior, before I got all fragile and he was promoted into my warm, wet shoes."Stay away from Brother Hildebrand, and you'll be just fine," he tells me. "There's sixteen other monks on his shift, go bother one of them. Talking of which," he adds, giving me what he fondly imagines is an intimidating stare, "what's all this about you handing out beatific visions like sweeties? You know perfectly well--"

I point out that I've already taken up far more of his valuable time than I could possibly deserve, and retire in good order, leaving him sullen and unhappy. Not, I hasten to add, intentionally. Just force of habit, I guess.

***

Something big involving a sleeper, an inside-man job. Ours, needless to say, is not to reason why, but inquiring minds want to know about things, and I have an inquiring mind. It's got me in trouble before now, and almost inevitably will again. Big deal.

That night, as I tickled the edges of one Brother Florian's consciousness with vague images of unimaginable transcendent wonder, I considered what I knew about various things: the political situation, the antecedents of Brother Hildebrand, the last recorded movements of various key players on both sides, one or two incidents from my own experience. I won't say a pattern started to emerge, but interesting shapes flickered in tantalizing fashion on the meniscus of the void, so much so that when I snapped out of it and looked round, I was alone in the chapel. There's always ten minutes or so between one shift clocking off and the next one filing in. It gives the vergers a chance to refill the lamps and do a spot of dusting.

It's just a job, that's all--a job for which we get no pay, no thanks, and a volcanic bollocking if things don't go exactly according to plan. We do it because that's who we are. You lot got free will; we were assigned our respective functions. We serve; therefore, we are. Furthermore (in theory, at least), every function in the divine service is of equal value, from archangels and cherubim down to night soil operatives and tempters. From each according to his ability, to each... Well, there is no to. We require nothing except work to do, which is provided for us, and we're supposed to be grateful.

Therefore, in the aftermath of the Unfortunate Event, there wasn't any punishment, as such. Perish the thought. Mercy and forgiveness are His middle names. What happened was that some of us who were doing jobs of equal value were reassigned to other jobs, also of equal value, jobs that the ones who chose the right side during the Event weren't awfully keen on doing, for some unfathomable reason. A minor adjustment in the great scheme of things, and the consensus of opinion is that we got off pretty lightly, all things considered.

True, no doubt. Even so.

Even before I was officially fragile, I relished (and still do) the very occasional moment of quiet, stillness, and peace. Not something I tend to encounter in my everyday life. When I'm on the job--was on the job, pre-fragile--it's often quiet, sneaking around on tiptoe so as not to alert the householder to your presence, but the stillness tends to be the pre-storm variety, and you can forget all about peace. When you're deep inside the mind of the sort of people we generally get called on to inhabit--let's say I've been in some pretty grim places in my time, and nearly all of them have had bone walls. It's noisy in there, what with all the sobbing and the yelling and the horrible vivid memories played back at maximum volume, over and over again. One thing you can't do under such conditions is hear yourself think. The Third Horn chapel is, by comparison, an earthly paradise.

The leading feature of the chapel, according to all the books, is the Great Iconostasis. Forty feet high and twenty-three across, with a gold leaf background that turns into a sheet of flame when the late-afternoon sun streams in through the rose window at precisely the first verse of evensong, it depicts the Sorrow of the Mother, which has always struck me as odd and just a smidgen off-color, doctrinally speaking. Brother Eusebius explains it by saying that just as human mortals can't look directly at the sun without damaging their optic nerves, they can't directly address Him face-to-face and person-to-person without risking spiritual damage--

("It makes you go blind, in other words."

He grins at me. "Exactly.")

--so they seek the intercession of an intermediary, in accordance with the properly constituted chain of command: priest to guardian angel to archangel to principality to power to virtue to dominion to throne to cherub to seraph to Holy Mother and eventually to the big boss himself. It's all about proper channels, which proverbially run deep, and doing things the right way, so that everybody knows where they stand, and the file copies end up in the right folders.

Color me unconvinced. I think it's something fundamental, part of your and our shared heritage. Throughout your history, and ours, we don't go to the king or the CEO or the governor of the province, because we're scum and we know it. No, instead we like to have a quiet word in the ear of someone who has the ear of the Big Man. As often as not, our hymn of supplication to the ear-haver has an instrumental accompaniment, the jingle of coins or the crackle of crisp notes, sweet music to charm the savage breast. It's the same rationale that worked so very well for Sighvat III. No point a creep like me asking for anything, but surely He'll listen to his own mother.

A creep like me. I slip unobtrusively into human form (look closely, and you'll see a densely packed swarm of tiny flies; best not to look too closely) and kneel, telling myself it's okay, it's just a picture, a picture of someone who never actually existed, since He never had a mother. I should know, I was there a fraction of a second later, and besides, I'm not praying, perish the thought, just taking the weight off my feet. I'm not praying, because prayer is basically just asking for stuff, and I have no stuff to ask for. But it's nice, once in a while, to stop and have a breather and pretend, just for a fleeting fraction of a moment, that I'm not me.

A shadow falls between me and the shining gold vision. I look over my shoulder. Oh, for crying out loud.

He grins at me. "You're going to be in so much trouble," he says.

Copyright © 2021 by K. J. Parker

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details