Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Engelbrecht

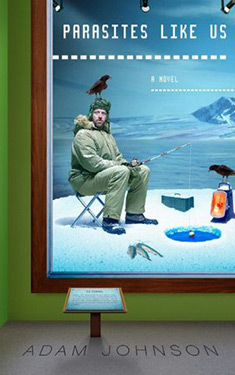

Parasites Like Us

| Author: | Adam Johnson |

| Publisher: |

Penguin Books, 2004 Viking, 2003 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The debut novel by the author of The Orphan Master's Son (winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize) and the story collection Fortune Smiles (winner of the 2015 National Book Award)

Hailed as "remarkable" by the New Yorker, Emporium earned Adam Johnson comparisons to Kurt Vonnegut and T.C. Boyle. In his acclaimed first novel, Parasites Like Us, Johnson takes us on an enthralling journey through memory, time, and the cost of mankind's quest for its own past.

Anthropologist Hank Hannah has just illegally exhumed an ancient American burial site and winds up in jail. But the law will soon be the least of his worries. For, buried beside the bones, a timeless menace awaits that will set the modern world back twelve thousand years and send Hannah on a quest to save that which is dearest to him. A brilliantly evocative apocalyptic adventure told with Adam Johnson's distinctive dark humor, Parasites Like Us is a thrilling tale of mankind on the brink of extinction.

Excerpt

Chapter One

This story begins some years after the turn of the millennium, back when gangs were persecuted, back before we all joined one. In those days, birds and pigs were still our friends, and we held some pretty crazy notions: People said the planet was warming. Wearing fur was a no-no. Dogs could do no wrong. Back then, we'd pretty much agreed that guns were good, that just about everybody needed one. Firearms, we were all to discover, were feeble, finicky things, prone to laughable inaccuracy.

During this brief moment in human evolution, a professor of anthropology might, for the half-year he worked, fish in the morning, lecture midday, and stroll excavation sites until early evening, after which was personal/leisure time. I was a professor of anthropology, one of the very, very few. I owned a bass boat, a classic Corvette, and a custom van, all of which I lost during the period of this story, the brief sentence I served inside the cushiest prison in the Western Hemisphere, the minimum-security federal prison camp at Parkton, South Dakota.

Camp Parkton, we called it. Club Fed.

As an anthropologist, I had the job of telling stories about the past. My area of study was the Clovis people, the first humans to cross the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia about twelve thousand years ago. As you know, the Clovis colonized a hemisphere that had never seen humans before, and their first order of business was to invent a new kind of spear point, which they used to eradicate thirty-five species of large mammals. The stories I told about the Clovis were not new ones: A people developed a technology that allowed them to exploit all their resources. They then created a vast empire. And once they had consumed everything in sight, they disbanded-in the case of the Clovis, into small groups that would form the roughly six hundred Native American tribes that exist today.

I had a '72 Corvette and a custom van!

Dear colleagues of tomorrow, fellow anthropologists of the future, how can I express my joy in knowing there is only one profession in the years to come, that each and every one of you has become a committed anthropologist? The trials of my life seem petty compared with their inevitable reward: that the turbulent story of our species should end with all its members' becoming experts on humanity.

The fate of the culture we called "America" is certainly no mystery to you. Of that tale, countless artifacts stand testament, and who could fail to hear such a song of conclusion, endlessly whistling through the frozen teeth of time? Yet you must have questions. Dig as you might, there must be gaps in the record. Who is buried in the Tomb of the Unknown Indian? you might ask. Was the hog truly smarter than the dreaded dog? Were owls really birds, or some other manner of animal? So, my dedicated peers, I will share with you how the betterment of humanity began, and let no one claim I slandered the past. I am the past.

I'm not sure I can tell you the exact year this story be- gins, but I'll never forget the day. It was the season in South Dakota in which the Missouri River nearly freezes over-day by day, shelves of white extend their reach from the riverbanks, calciumlike, until they enter the central channel, where the current rips great sheets free and sends them hurtling downstream.

From my office on the campus of the University of Southeastern South Dakota, I could hear the frozen river wail and moan before a lurching crack tore loose a limb of ice. When the day was clear, I could even see from my window in the anthropology building scattered stains of red on the ice, where eagles had landed with freshly snatched fish and stripped them on the frozen ledges. An eagle was a kind of bird, quite large, and it was famous for the boldness it displayed when stealing another's prey. Most birds were about the size of rats, though some came as big as jackrabbits. The eagle, however, weighed in closer to a dog. Picture a greyhound, then add ferocity and wings.

It was a gray, brooding day when Eggers, one of my star doctoral students, stuck his head in my office. He was vigorously chewing something, and the odds were it wasn't gum.

Eggers wore goatskin breeches and a giant poncho of dark, matted fur, which he'd fashioned himself from animal hides begged off the Hormel meatpacking plant at the edge of town. I could smell him long before he made his way to the stacks of cardboard boxes that filled my doorway and spilled into the hall.

"Careful of Junior," I said and waved him in. I had just received an exciting new crate of raw ice-core data from Greenland, and Eggers' booties were covered with God-knows-what.

"Life's good, Dr. Hannah," Eggers said, making his way around the boxes. He displayed that impish grin of his. "Life is good," he repeated.

My office in those days was filled with houseplants of every variety, though I found indoor gardening so pointless and sad I could barely stand to look at them. Eggers ducked under the hanging tendrils of plants whose names escaped me, his feet crunching across the layer of flint chips that littered the floor from the hours I whiled away knapping out primitive tools and weapons.

He took a seat, and I was confronted with my daily update on Eggers' dissertation project, which was to exist using nothing but Paleolithic technology for an entire year. More than eleven months into the experiment, some of the results were already clear: the wafting custard of his breath, the thin mistletoe of his beard, the way the oiled gloss of his face had attained the yellowy hue of earwax.

I should have been working on a grant proposal or grading some of the endlessly simple student papers that flowed across my desk. But I couldn't concentrate, because of Glacier Days, a yearly carnival intended to lighten the gloom of winter by celebrating the recession of the glaciers that had carved the Missouri River Valley. They'd set up the midway in the Parkton Square parking lot, catty-corner to campus, and every so often you'd hear the muffled, rising moan and long wail of young people on the thrill rides.

"Okay, Eggers," I said. "Life's grand. We'll go with that hypothesis."

Eggers shrugged, as if everything was self-evident. "Oh, it's not some theory, Dr. Hannah. Life is tiptop," he said, moving aside a dusty stack of my book, The Depletionists, and settling into a high-backed chair. He slumped enough that his hair left a sheeny streak down the leather upholstery. God, his game bag reeked!

I was about to hear one of Eggers' continuing intrigues with a coed, or how he'd won some prestigious new grant. The anthropology journals were already fighting to publish his story. But I couldn't get that "life is good" phrase out of my head. It's what my stepmother, Janis, kept saying at the end, and it became one of my father's refrains after we lost her. I could see behind Eggers, framed in the window, a piece of ice slowly turning down the Missouri River-it drifted in from the future, caught the sun for a moment, and disappeared out into the past. From the Glacier Days carnival, a slow whoop arose from the next generation of South Dakotans as they mocked their deaths on bloodcurdling rides, and my eyes naturally fell to Junior-nineteen thousand notecards and twenty-seven cardboard boxes of research, all yet to be examined, all those stories waiting to be told.

Eggers shifted what he was chewing and went after it with his molars.

"Is this about Trudy?" I asked.

"Trudy? Why bring her up?" he asked. "Are you feeling guilty, Dr. Hannah?"

"What would I have to feel guilty about?"

"Nothing," Eggers said. "Nothing. Except you did file the paperwork to revoke her Peabody Fellowship and give it to me."

"The school's doing that. That's out of my hands. Congrats, by the way."

"You know me, Dr. Hannah. I yawn at money. Money's obsolete to me."

Eggers pulled something out of his mouth, inspected it, and put it back in.

"Don't gloat," I told him. "Everything will be hunky-dory once I explain things to her."

"Trudy's pretty upset. I mean, I was the one who broke it to her."

"This isn't even official yet."

"She needed to hear it from someone who cared," Eggers said.

"Please," I said. "Anyway, that's only half the story. Losing her Peabody is only the bad news of a good-news/bad-news thing. I'll explain it to her."

Eggers swallowed hard enough to make his eyes water, and then he opened the flap of his game bag. I could see a fuzzy tail sticking out of it, and it hadn't escaped the notice of the school paper that all the squirrels on campus had disappeared during the time that Eggers, an adult omnivore, had taken up residence in the middle of the quad.

"I wouldn't worry about Trudy," Eggers said. "Trudy can take care of herself. She'll bounce back." He removed another sinewy morsel and slid it into his mouth. Though grayish-brown, it crunched like celery. He chewed it contemplatively. "I've got my own good and bad news," he added.

I removed my glasses, folded them, rubbed the bridge of my nose.

"Just the good," I said. "Only tell me the good."

"I found something."

Eggers was always finding things. He was the only person in town who walked everywhere, and over eleven months, his travels on foot had netted him countless arrow points, bison skulls, mastodon teeth, and a brass bell that may or may not have belonged to Meriwether Lewis. Sleeping in the same stretch of sand in South Dakota, you were likely to find a buffalo soldier's pistol, a conquistador's breastplate, the hooves of rhino-pigs from the early Eocene, T-rex teeth, and maybe even a Cambrian trilobite, frozen mid-wriggle at the dawn of time.

"Is it a spear point?" I asked.

"It's a point, all right," Eggers said.

"A Clovis point?"

Eggers shrugged, but in a way that said, You can bet the farm.

I threw a foot up on my desk to lace ...

Copyright © 2003 by Adam Johnson

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details