Added By: charlesdee

Last Updated: charlesdee

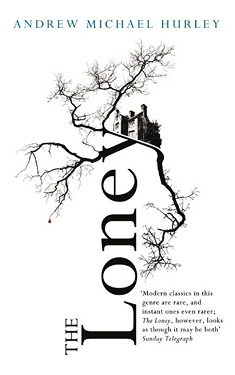

The Loney

| Author: | Andrew Michael Hurley |

| Publisher: |

Houghton Mifflin, 2016 John Murray, 2015 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Horror |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Gothic |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The eerie, suspenseful debut novel -- hailed as "an amazing piece of fiction" by Stephen King -- that is taking the world by storm.

When the remains of a young child are discovered during a winter storm on a stretch of the bleak Lancashire coastline known as the Loney, a man named Smith is forced to confront the terrifying and mysterious events that occurred forty years earlier when he visited the place as a boy. At that time, his devoutly Catholic mother was determined to find healing for Hanny, his disabled older brother. And so the family, along with members of their parish, embarked on an Easter pilgrimage to an ancient shrine.

But not all of the locals were pleased to see visitors in the area. And when the two brothers found their lives entangling with a glamorous couple staying at a nearby house, they became involved in more troubling rites. Smith feels he is the only one to know the truth, and he must bear the burden of his knowledge, no matter what the cost. Proclaimed a "modern classic" by the Sunday Telegraph (UK), The Loney marks the arrival of an important new voice in fiction.

Excerpt

1

It had certainly been a wild end to the autumn. On the Heath a gale stripped the glorious blaze of colour from Kenwood to Parliament Hill in a matter of hours, leaving several old oaks and beeches dead. Mist and silence followed and then, after a few days, there was only the smell of rotting and bonfires.

I spent so long there with my notebook one afternoon noting down all that had fallen that I missed my session with Doctor Baxter. He told me not to worry. About the appointment or the trees. Both he and Nature would recover. Things were never as bad as they seemed.

I suppose he was right in a way. We'd been let off lightly. In the north, train lines had been submerged and whole villages swamped by brown river water. There had been pictures of folk bailing out their living rooms, dead cattle floating down an A road. Then, latterly, the news about the sudden landslide on Coldbarrow, and the baby they'd found tumbled down with the old house at the foot of the cliffs.

Coldbarrow. There was a name I hadn't heard for a long time. Not for thirty years. No one I knew mentioned it any more and I'd tried very hard to forget it myself. But I suppose I always knew that what happened there wouldn't stay hidden forever, no matter how much I wanted it to.

I lay down on my bed and thought about calling Hanny, wondering if he too had seen the news and whether it meant anything to him. I'd never really asked him what he remembered about the place. But what I would say, where I would begin, I didn't know. And in any case he was a difficult man to get hold of. The church kept him so busy that he was always out ministering to the old and infirm or fulfilling his duties to one committee or another. I could hardly leave a message, not about this.

His book was on the shelf with the old paperbacks I'd been meaning to donate to the charity shop for years. I took it down and ran my finger over the embossed lettering of the title and then looked at the back cover. Hanny and Caroline in matching white shirts and the two boys, Michael and Peter, grinning and freckled, enclosed in their parents' arms. The happy family of Pastor Andrew Smith.

The book had been published almost a decade ago now and the boys had grown up -- Michael was starting in the upper sixth at Cardinal Hume and Peter was in his final year at Corpus Christi -- but Hanny and Caroline looked much the same then as they did now. Youthful, settled, in love.

I went to put the book back on the shelf and noticed that there were some newspaper cuttings inside the dust jacket. Hanny visiting a hospice in Guildford. A review of his book in the Evening Standard. The Guardian interview that had really thrust him into the limelight. And the clipping from an American evangelical magazine when he'd gone over to do the Southern university circuit.

The success of My Second Life with God had taken everyone by surprise, not least Hanny himself. It was one of those books that -- how did they put it in the paper? -- captured the imagination, summed up the zeitgeist. That kind of thing. I suppose there must have been something in it that people liked. It had bounced around the top twenty of the bestsellers list for months and made his publisher a small fortune.

Everyone had heard of Pastor Smith even if they hadn't read his book. And now, with the news from Coldbarrow, it seemed likely that they would be hearing of him again unless I got everything down on paper and struck the first blow, so to speak.

2

If it had another name, I never knew, but the locals called it the Loney -- that strange nowhere between the Wyre and the Lune where Hanny and I went every Easter time with Mummer, Farther, Mr and Mrs Belderboss and Father Wilfred, the parish priest. It was our week of penitence and prayer in which we would make our confessions, visit Saint Anne's shrine, and look for God in the emerging springtime, that, when it came, was hardly a spring at all; nothing so vibrant and effusive. It was more the soggy afterbirth of winter.

Dull and featureless it may have looked, but the Loney was a dangerous place. A wild and useless length of English coastline. A dead mouth of a bay that filled and emptied twice a day and made Coldbarrow -- a desolate spit of land a mile off the coast -- into an island. The tides could come in quicker than a horse could run and every year a few people drowned. Unlucky fishermen were blown off course and ran aground. Opportunist cocklepickers, ignorant of what they were dealing with, drove their trucks onto the sands at low tide and washed up weeks later with green faces and skin like lint.

Sometimes these tragedies made the news, but there was such an inevitability about the Loney's cruelty that more often than not these souls went unremembered to join the countless others that had perished there over the centuries in trying to tame the place. The evidence of old industry was everywhere: breakwaters had been mashed to gravel by storms, jetties abandoned in the sludge and all that remained of the old causeway to Coldbarrow was a line of rotten black posts that gradually disappeared under the mud. And there were other, more mysterious structures -- remnants of jerry-built shacks where they had once gutted mackerel for the markets inland, beacons with rusting fire-braces, the stump of a wooden lighthouse on the headland that had guided sailors and shepherds through the fickle shift of the sands.

But it was impossible to truly know the Loney. It changed with each influx and retreat of water and the neap tides would reveal the skeletons of those who thought they had read the place well enough to escape its insidious currents. There were animals, people sometimes, the remains of both once -- a drover and his sheep cut off and drowned on the old crossing from Cumbria. And now, since their death, for a century or more, the Loney had been pushing their bones back inland, as if it were proving a point.

No one with any knowledge of the place ever went near the water. No one apart from us and Billy Tapper that is.

Billy was a local drunk. Everyone knew him. His fall from grace to failure was fixed like the weather into the mythology of the place, and he was nothing short of a gift to people like Mummer and Father Wilfred who used him as shorthand for what drink could do to a man. Billy Tapper wasn't a person, but a punishment.

Legend had it that he had been a music teacher at a boys' grammar school, or the head of a girls' school in Scotland, or down south, or in Hull, somewhere, anywhere. His history varied from person to person, but that the drink had sent him mad was universally accepted and there were any number of stories about his eccentricities. He lived in a cave. He had killed someone in Whitehaven with a hammer. He had a daughter somewhere. He thought that collecting certain combinations of stones and shells made him invisible and would often stagger into the Bell and Anchor in Little Hagby, his pockets chinking with shingle, and try to drink from other people's glasses, thinking that they couldn't see him. Hence the dented nose.

I wasn't sure how much of it was true, but it didn't matter. Once you'd seen Billy Tapper, anything they said about him seemed possible.

Copyright © 2015 by Andrew Michael Hurley

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details