Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: christopherw277

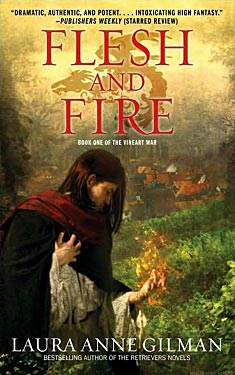

Flesh and Fire

| Author: | Laura Anne Gilman |

| Publisher: |

Pocket Books, 2009 |

| Series: | The Vineart War: Book 1 |

|

1. Flesh and Fire |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Mythic Fiction (Fantasy) |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: | |

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Once, all power in the Vin Lands was held by the prince-mages, who alone could craft spellwines, and selfishly used them to increase their own wealth and influence. But their abuse of power caused a demigod to break the Vine, shattering the power of the mages. Now, fourteen centuries later, it is the humble Vinearts who hold the secret of crafting spells from wines, the source of magic, and they are prohibited from holding power.

But now rumors come of a new darkness rising in the vineyards. Strange, terrifying creatures, sudden plagues, and mysterious disappearances threaten the land. Only one Vineart senses the danger, and he has only one weapon to use against it: a young slave. His name is Jerzy, and his origins are unknown, even to him. Yet his uncanny sense of the Vinearts' craft offers a hint of greater magics within -- magics that his Master, the Vineart Malech, must cultivate and grow. But time is running out. If Malech cannot teach his new apprentice the secrets of the spellwines, and if Jerzy cannot master his own untapped powers, the Vin Lands shall surely be destroyed.

In Flesh and Fire, first in a spellbinding new trilogy, Laura Anne Gilman conjures a story as powerful as magic itself, as intoxicating as the finest of wines, and as timeless as the greatest legends ever told.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

House of Malech: Harvest

The boy focused on what he was doing, but not so much that he failed to sense someone pause behind him, too close for comfort. He managed not to flinch as the older slave bent down to whisper. "Nice job you pulled, Fox-fur. Who'd you sweetmouth for it?"

The boy grunted, not wanting to talk, even to defend himself. Talk got you noticed. Notice was bad. Keep your face down, your hands busy, and your mouth shut, and survive. Those were the unspoken rules everyone knew.

After a minute the other slave shrugged and moved on with his own assignment. Left alone, the boy looked up into the sky, his eyes squinting as he searched the pale blue distance. He hadn't sweet-mouthed anyone. Luck of the pick, was all. He wasn't going to question it. He didn't question anything; he just did as he was told.

The brightness of the open sky made his eyes water. There was a bird -- a tarn, from the banding -- flying overhead in search of a careless or greedy rabbit. Every year they cut back the brush to the ancient grove of trees that marked the end of the vineyard, trying to keep the rabbits and foxes from the vines. They had built stone fences and decanted spells to keep humans away, but animals were harder to convince.

This field, and the rest of it, was part of the Valle of Ivy. The valley was cut into a chessboard of fields, half green with crops, the others brown and fallow, interspersed with the occasional gnarled fruit tree, and dotted with low stone buildings. In the distance a river cut through the fields -- the Ivy. The chessboard and the buildings belonged to the House of Malech, one of four Vinearts established within The Berengia, and the only one currently ranked Master. His master. The slave knew nothing of the other Vinearts or The Berengia, or what lay beyond her borders. To imagine anything beyond the vineyard and the sleep house was as impossible as flying with the tarn overhead.

At the far edge of the fields where the boy was stationed, a pair of trees -- not quite so ancient, but still wider around than a man could reach -- created a shelter for two low structures built of pale gray stone: the slaves' sleep house and vineyard's storehouse, where the plows and tools were kept. Those, and the open form of the vintnery behind him, made of the same stone as the enclosure's walls, were the boundaries of his world. The other buildings behind the vintnery, across a wide cobbled road, might as well have been on the other side of the Ivy, for all he knew of them.

The boy looked away from the sky and downward. Every slave in the House of Malech was working today. Summer had been warm and rainy, but those days had given way to cooler, drier mornings, and the grapes had ripened on schedule, green leaves turning a dark red at the edges, the grapes darker red yet, their skin tight over plump, juicy flesh. He could practically feel the ripeness in the air, waiting. He had learned the hard way not to mention that to anyone, the way the ripening grapes made a noise in his head, inside his bones. The one time he had asked another slave about it, he'd got beaten until his skull had bled, and the overseer had kept him out of the yards for the day.

The tarn had disappeared while he'd looked away. Now not even a cloud marred the expanse of blue, the sun already high overhead and surprisingly strong for the season. A faint breeze came down off the ridge, carrying a salty hint that cooled the sweat on his skin just enough to make it noticeable. The boy shifted, making himself as comfortable as he could, glad at least to be out of the direct sunlight, out of the fields. In the distance, past the vintner's shed, beyond the dark gray bulk of the sleep house, two score of slaves, stripped down to their loose-woven pants, worked their way up and down the groupings of waist-high vines, carefully stripping the ripe bunches from each plant one handful at a time, bending and rising in tune to some unheard rhythm.

He had done that, for three Harvests before this one, once he was old enough to be trusted. Your hands cramped after a while, and every finger cracked and bled, but not a single fruit was damaged if you could help it; each straw basket on their backs, once filled, was worth more than the slave carrying it. That was the first thing learned the very first day a slave was brought into the vineyard. You learned, and you survived, and, if your master was kind, you might even make it out of the yards, out of the sun and the rain, and away from walking stooped all your waking hours until you slept that way, too.

His master was not kind, but neither was he particularly cruel, and the boy had made it out of the yard. Barely.

Barely was enough. He could sit, and his back did not hurt, and his skin was not blistered by the sun. The Washer who traveled their road would say it was because he let the world move him rather than trying to move it. He didn't see how he could do otherwise. But there was much the Washers preached that he didn't understand.

A harvest-hire guard stood on the top of a slight rise at the edge of the field, watching the activity. A stiffened lash in his left hand tapped an irregular rhythm against his thigh as his gaze skimmed over the area being harvested. He was there more for tradition than need. It was death to steal a clutch of grapes. Death to taste one. Death to waste one. Nobles could afford spellwine, and free men might drink of vin ordinaire: slaves could not even dream of either.

The boy shifted, feeling warning prickles in his bare feet that told him he had been still too long. He looked away from the guard, letting his gaze rest on nothing in particular, waiting. That was best, to simply wait, and not draw attention.

When a basket was filled to near overflowing with fruit, the slave carrying it would place it to one side of the trellis-lane. A younger slave, not yet trusted with the picking, would come down to fetch it, leaving an empty basket in its place to be filled in turn. That slave would bring the full basket down, away from the vineyard itself to the crusher, a great wooden monster construct twice as high as a grown man and four times the length.

That was where the boy waited. His responsibility was to monitor the fill level of the wooden crusher, making sure that the right amount of fruit was added, no more and no less.

The other slave had been right; it was a good job. It was also an important job, a sign that the overseer was not displeased with him, and he felt the responsibility keenly. But the truth was that it was boring, and his legs kept falling asleep.

An old slave, his wizened limbs useless for anything else, watched from the other side, sitting in a raised wooden chair to make sure that every fruit was placed into the great wooden monster and that no slave sneaked even one fruit into his mouth. He was also there to ensure that no fingers or clothes were trapped in the process. Every year at least one slave was maimed or killed that way, the weights and beams catching the unwary or the careless. The boy had worked six Harvests since the Master bought him and seen the results: slaves missing fingers and, in one case, an entire arm, crushed to uselessness and cut off before it could turn black and stink.

Two baskets were emptied into the maw of the monster, then a third. The old slave nodded at the boy, licking his cracked, dry lips in a way that reminded the boy of the lizards that sunned themselves on the low stone walls between the vineyards. The boy looked away again, focusing all of his attention on the crusher, as though that would make the old man go away. Harvest stories weren't the only ones told in the sleep house. The younger slaves knew to stay away from that one's hands in the darkness, or when they used the shit pits at night.

The slavers had men like that, too. He had been younger then, too young, and not as careful. But the slavers were past, done with him now that he belonged to another.

The other slaves might fumble under blankets or up against shadowed walls, willingly or not. Here the boy learned how to say no without saying anything at all, to evade reaching hands without giving offense, and even as those his own age began to look around with an interested eye, he felt no desire at all, not even to use his own hand, as the others did. Fortunately, hard work and a sudden growth over the winter had finally turned his rounded limbs into harder muscle, so a slave grabbed at him at his own risk now, and the overseer had shown no interest in flesh, save that it did the work assigned to it.

That thought in mind, when the fourth basket was emptied into the belly of the crusher, he darted forward and looked inside. A dark line, the stain of years of pressings, marked the three-quarter point. The boy waved his hand in a circular motion, and one more basket was dumped in, then the heavy door was slid shut. The boy stepped back, out of harm's way, as the crusher was turned upside down with a creaking, moaning noise, like a giant moaning in his sleep. Pressure in the form of giant bladders was applied, another slave working the bellows to fill the bladders until given the command to stop, and then deflating it again. Once, he had been told, slaves did this work with their feet. Too many grapes were lost that way, the process too slow. He wondered about the feel of grapes under the soles of his feet and between his toes, tread upon like dirt, and could not imagine it.

"A good harvest, this year."

The boy tensed, his shoulders hunching up around his ears even more than usual. He had been so preoccupied with his boredom and his prickling legs, he hadn't noticed the overseer leaving his usual post and coming to stand behind him.

Stupid, stupid, he thought, trying to become invisible. The overseer had never hurt him, but you never knew what might catch his attention, and unlike the other slaves, you could not ignore him, or make him go away. The overseer was all-powerful. Even the season-hire guards were scared of the overseer.

"We shall see."

The other voice was deeper, dryer, unfam...

Copyright © 2009 by Laura Anne Gilman

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details