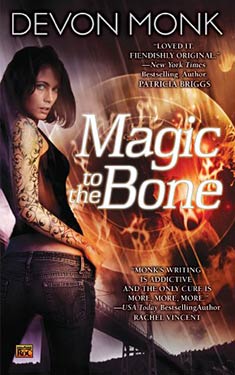

Magic to the Bone

| Author: | Devon Monk |

| Publisher: |

Penguin Books, 2011 Roc, 2008 |

| Series: | Allie Beckstrom: Book 1 |

|

1. Magic to the Bone |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Devon Monk is casting a spell on the fantasy world...

Using magic means it uses you back, and every spell exacts a price from its user. But some people get out of it by Offloading the cost of magic onto an innocent. Then it's Allison Beckstrom's job to identify the spell-caster. Allie would rather live a hand-to-mouth existence than accept the family fortune--and the strings that come with it. But when she finds a boy dying from a magical Offload that has her father's signature all over it, Allie is thrown back into his world of black magic. And the forces she calls on in her quest for the truth will make her capable of things that some will do anything to control...

Excerpt

It was the morning of my twenty fifth birthday, and all I wanted was a decent cup of coffee, a hot breakfast, and a couple hours away from the stink of used magic that seeped through the walls of my apartment building every time it rained.

My current fortune of ten bucks wasn't going to get me that hot breakfast, but it was going to buy a good dark Kenya roast and maybe a muffin down at Get Mugged. What more could a girl ask for?

I took a quick shower, pulled on jeans, a black tank top, and boots. I brushed my dark hair back and tucked it behind my ears, hoping for the short, wet, sexy look. I didn't bother with makeup. Being six foot tall and the daughter of one of the most notorious businessmen in town got me enough attention. So did my pale green eyes, athletic build, and the family knack for coercion.

I pulled on my jacket, careful not to jostle my left shoulder too much. The scars across my deltoid still hurt, even though it had been three months since the creep with the knife had jumped me. I had known the scars might be permanent, but I didn't know they would hurt so much every time it rained. Blood magic, when improperly wielded by an uneducated street hustler, was a pain that just kept on giving. Lucky me.

One of these days, when my student loans were paid off and I'd dug my credit rating out of the toilet, I'd be able to turn down cheap Hounding jobs that involved back-alley drug deals and black-market revenge spells. Hell, maybe I'd even have enough money to afford a cell phone again.

I patted my pocket to make sure the small, leather-bound book and pen were there. I didn't go anywhere without those two things. I couldn't. Not if I wanted to remember who I was when things went bad. And things seemed to be going bad a lot lately.

I made it as far as the door. The phone rang. I paused, trying to decide if I should answer it. The phone had come with the apartment, and like the apartment it was as low-tech as legally allowed, which meant there was no caller ID.

It could be my dad - or more likely his secretary of the month - delivering the obligatory annual birthday lecture. It could be my friend Nola, if she had left her farm and gone into town to use a pay phone. It could be my landlord asking for the rent I hadn't paid. Or it could be a Hounding job.

I let go of the doorknob and walked over to the phone. Let the happy news begin.

"Hello?"

"Allie, girl?" It was Mama Rossitto, from the worst part of North Portland. Her voice sounded flat and fuzzy, broken up by the cheap landline. Ever since I did a couple Hounding jobs for Mama a few months ago, she treated me like I was the only person in the city who could trace lines of magic back its user and abuser.

"Yes, Mama, it's me."

"You fix. You fix for us."

"Can it wait? I was headed to breakfast."

"You come now. Right now." Mama's voice had a pitch in it that had nothing to do with

the bad connection. She sounded panicked. Angry. "Boy is hurt. Come now."

The phone clacked down, but must not have hit the cradle. I heard the clash of dishes

pushed into the sink, the sputter of a burner snapping to life, then Mama's voice, farther off, shouting to one of her many sons - half of whom were runaways she'd taken in - all of whom answered to the name Boy.

I heard something else too, a high, light whistle like a string buzzing in the wind, softer than a wheezy newborn. I'd heard that sound before. I tried to place it, and found holes where my memory should be.

Great.

Using magic meant it used you back. Forget the fairy-tale hocus-pocus, wave a wand and bling-o, sparkles and pixie dust crap. Magic, like booze, sex, and drugs, gave as good as it got. But unlike booze and the rest, magic could do incredible good. In the right hands, used the right way, it could save lives, ease pain, and streamline the complexities of the modern world. Magic was revolutionary, like electricity, penicillin, and plastic, and in the thirty years since it had been discovered and made accessible to the general public, magic had done a lot of good.

At first, everyone wanted a piece of it - magically enhanced food, fashion, entertainment, sex. And then the reality of such use set in. Magic always takes its due from the user, and the price is always pain. It didn't take people long to figure out how to transfer that pain to someone else, though.

Laws were put in place to regulate who could access the magic, and how and why. But there weren't enough police to keep up with stolen cars and murders in the city, much less the misuse of a force no one can see.

Things went downhill fast, and as far as I can tell, they had stayed there.

But while magic made the average Joe pay one painful price each time he used it, sometimes magic double dipped on me. I'd get the expected migraine, flu, roaring fever, or whatever, and then, just for fun, magic would kick a few holes in my memories. It didn't happen every time, and it didn't happen in any pattern or for any reason I could fathom. Just sometimes when I use magic, it makes me pay the price in pain, then takes a few of my memories for good measure.

That's why I carried a little blank book - to record important bits of my life. And it's also why four years at Harvard, pounding tomes for my masters in business magic hadn't worked out quite the way I'd wanted it to. Still, I was a Hound, and I was good at it. Good enough that I could keep food on the table, live in the crappiest part of Old Town, and make the minimum payment on my student loans. And hey, who didn't have a few memories they wouldn't mind getting rid of, right?

The phone clattered and the line went dead.

Happy birthday to me.

If Boy had been hurt by magic, Mama should have called 911 for a doctor who knew how to handle those sorts of things, not a Hound like me. Suspicious and superstitious, Mama always thought her family was under magical attack. Not one of the times I'd Hounded for her, had her problem been a magical hit. Just bad luck, spoiled meat, and, once, cockroaches the size of small dogs (shudder).

But I had done some other jobs since I'd set up shop here in Portland. Every one of those sent me sniffing the illegal magical Offloads back to corporations. And nine times out of nine, even that kind of proof, my testimony on the stand, and a high-profile trial wouldn't get the corporation much more than a cash penalty.

I rolled my good shoulder to try to get the kink out of my neck, but only managed to make my arm hurt more. I didn't want to go. But I couldn't just ignore her call, and there was no other way to get in touch with her. Mama wouldn't answer the phone. She was convinced it was tapped, though I couldn't think of anyone who would be interested in the life of a woman who lived in North Portland, in the broken-down neighborhood of St. Johns, a neglected and mostly forgotten place cut off from the magic that flowed through rest of the city.

I tipped my head back, stared at the ceiling, and exhaled. Okay. I'd go and make sure Boy was all right. I'd try to talk Mama into calling a doctor. I'd check for any magical wrongdoing. I'd look for rats. I'd bill her half price. Then I would go out for a late birthday breakfast.

A girl could hope, anyway.

I walked out the door and locked it. I didn't bother with alarm spells. Most single women in the city thought alarm spells would keep them safe, but I knew firsthand that if someone wanted to break into your apartment badly enough, there wasn't a spell worth paying the price for that could keep them out.

I took the stairs instead of the elevator, because I hate small spaces, and made it to the street in no time. The mid-September morning was gray as a grave and cold enough that my breath came out in plumes of steam. The wind gusted off the Willamette River and rain sliced at my face.

Portland lived up to its name. Even though it was a hundred miles from the Pacific ocean, it had that crumbling-brick-warehouse and industrial feel of the working port it still was, especially where it had built along the banks of the Willamette and Columbia rivers. The Willamette River was practically in my backyard, behind the warehouses and the train and bus stations. Without squinting I could see four of the mismatched bridges that crossed the water, connecting downtown with the east side of the city. Over that river and north, close to where the Willamette and Columbia met, was Mama's neighborhood.

I zipped my coat, pulled up my hood, and wished I'd thought about putting on a sweater before I left.

A bus wouldn't get me to Mama's fast enough. However, the good thing about being a d six-foot-tall woman, was that cabs, few and far between though they may be, stopped when you whistled. It didn't hurt that I had my dad's good looks, either. When I was in the mood to smile, I could get almost anyone to see things my way, even without using magic. True to the Beckstrom blood, I also had a gift for magic-based Influence. But after watching my dad Influence my mother, his lovers, business partners, and even me to get his way, I'd sworn off using it.

It wasn't like I had wanted to go to Harvard. I had Juilliard in mind: art, not business; music, not magic. But my dad had severe ideas about what constituted a useful education.

I waved down a black-and-white taxi and ducked into the backseat. The driver, a skinny man who smelled like he brushed his hair with bacon drippings, glanced in the rearview. "Where to?"

"St. John's."

His eyes narrowed. I watched him consider telling a nice girl like me about a bad side of town like that. But he must have decided a fare's a fare, and a one-way was better than none at all. He pulled into traffic and didn't look back at me again.

In the best light, like maybe a sunny day in July, the north side of Portland looks like a derelict row of crumbling shops and broken-down bars. On a cold, rainy September day like today, it looks like a wet derelict row of crumbling shops and broken-down bars.

Crawling up from the river, the neighborhood had that rotten-tooth brick-and-board architecture that attracted the poor, the addicted, and the desperate. Unlike most of the rest of the Portland, it stood pretty much how it had been built back in the 1800s, except it had one other thing going against it - there was no naturally occurring magic beneath the streets of North Portland. The city had conveniently forgotten to add the fifth quadrant of town into the budget when running the lead and glass networks to make magic available, so now the rest of the city largely ignored the entire area, like a sore beneath the belt everyone knew about, but no one mentioned in polite company.

The driver rolled the cab to a stop just on the other side of the railroad track, and I couldn't help but smile. He must have heard of the neighborhood's rules and rep. Outsiders were tolerated in St. John's most days. Only no one knew which days were most days.

"Want me to wait?" he asked, even though he probably already knew my answer.

"No," I said, "I'll bus home. Will ten cover it?" He nodded, and I pressed the money into his hand. I pushed the door open against the wind and got a face full of rain.

I stepped onto the sidewalk and got moving. Mama's wasn't far. I took a couple deep breaths, smelled rain, diesel and the pungent dead-fish-and-salt stench off the river. When the wind shifted, I got a noseful of the sewage treatment plant. Then I caught a hint of something spicy - peppers and onions and garlic from Mama's restaurant - and grinned.

I didn't know why, but coming to this part of town always put me in a better mood. Maybe it was a sick sort of kinship, knowing that other people were holding together while everything was falling apart too. There was a certain kind of honesty in the people who lived here, an honesty in the place. No magic to keep the storefronts permanently shiny and clean, no magic to whisk away the stink of too many people living too close together, no magic to give the illusion that everyone wore thousand-dollar designer shoes. I liked the honesty of it, even if that honesty wasn't always pretty.

Or maybe it was just that I figured it was the last place my dad, or anyone else who expected me to do better by myself (read: do what they wanted me to do) would ever expect to find me. There was something good about this rotten side of town. Something invisible to the eye, but obvious to the soul.

Except for piles of cardboard and a few rusting shopping carts, the street was empty - a hard rain will do that - so it was easy to spot the motion from the doorway to my left. I didn't even have to turn my head to know it was a man, dark, an inch or two taller than me, wearing a blue ski coat and black ski hat. From the stink of cheap cologne - something with so much pine overtone, I wondered if he had splashed toilet cleaner over his head by mistake - I knew it was Zayvion Jones.

He was new to town, maybe two months or so, and so unpretentiously gorgeous that even the ratty ski coat and knit hat couldn't stop my stomach from flipping every time I saw him. I knew nothing else about him except that he liked to hang around the edges of North Portland, didn't appear to be dealing drugs or magic, or doing much of anything else, really. Since he'd shown me no reason to trust or distrust him yet, out of convenience I distrusted him.

"Morning, Ms. Beckstrom," he said with a voice too soft to belong to a street thug.

"Not yet, it isn't." I glanced at him. He had a good, wide smile and a high arc to his cheeks that made me think he had Asian or Native along with the African in his bloodline.

"Might be better soon," he said. "Buy you breakfast?"

"With what? The fingers in your pocket?"

He chuckled. It had a nice sound to it.

My stomach flipped. I ignored it and kept walking.

"Maybe dinner some time?" he asked.

Mama's place was a squat two story restaurant with living space on the top floor and eating space on the bottom. It was just a couple blocks down, a painted brick and wood building hunkered against the broody sky. I stopped and turned toward Zayvion. Now that I looked closer, I realized he had good eyes too, brown and soft, and the kind of wide shoulders that said he could hold his own in a fight. He looked like somebody you could trust, somebody who would tell you the truth no matter what, and hold you if you asked, no explanation needed.

Why he was following me around made me suspicious as hell.

I thought about drawing on magic to find out if he was tied to someone's magical strings. Even though St. John's was a dead zone, Hounding wasn't impossible to do here. It just meant having to stretch out to tap into the city's nearest lead and glass conduits that stored and channeled magic, or maybe reach even deeper than that and access the natural magic that pooled like deep cisterns of water beneath all other parts of Portland.

But I had sworn off using magic unless necessary. Losing bits of one's memory will make those sorts of resolutions stick. I wasn't about to pay the price of Hounding a man who was more annoyance that threat. Still, he deserved a quick, clear signal that he was wasting his time.

"Listen. My social life consists of shredding my junk mail and changing the rat traps in my apartment. It's working for me so far. Why mess with a good thing?"

Those soft brown eyes weren't buying it, but he was nice enough not to say so. "Some other time maybe," he said for me.

"Sure." I started walking again and he came along with me, like I had just told him we were officially long lost best friends.

"Did Mama call you?" he asked.

"Why?"

"I told her Boy needed an ambulance, but she wouldn't listen to me."

I didn't bother asking why again. I jogged the last bit to the restaurant and took the three wooden steps up to the door. Inside was darker than outside, but it was easy to see the lay of things. To the right, ten small tables lined the wall. To the left, another three. Ahead of me, one of Mama's Boy's - the one in his thirties who spoke in single syllable words - stood behind the bar. The only phone in the place was mounted against the wall next to the kitchen doorway. Boy watched me walk in, looked over my shoulder at Zayvion, and didn't miss a beat letting go of the gun I knew he kept under the bar. He pulled out a cup instead and dried it with a towel.

"Where's Mama?" I asked.

"Sink," Boy said.

I headed to the right, intending to go behind Boy and the bar, and into the kitchen.

I stopped cold as the stench of spent magic, oily as hot tar, triggered every Hound instinct I had. Someone had been doing magic, using magic, casting magic, in a big way, right here on this very unmagical side of town. Or someone somewhere else had invoked a hell of a Disbursement spell to Offload that much magical waste into this room.

I tried breathing through my mouth. That didn't make things better, so I put my hand over my mouth and nose. "Who's been using magic?"

Boy gave me a sideways look, one that flickered with fear.

Mama's voice boomed from the kitchen, "Allie, that you?" and Boy's eyes went dead. He shrugged.

I pulled my hand away from my mouth. "Yes. What happened?"

Mama, five foot two and one-hundred percent street, shouldered through the kitchen doors, holding the limp body of her youngest Boy, who had turned five about a month ago. "This," she said. "This is what happened. He's not sick from fever. He hasn't fallen down. He's a good boy. Goes to school every day. Today, he doesn't wake up. Magic, Allie. Someone hit him. You find out who. You make them pay."

Mama hefted Boy up onto the bar, but didn't let go of him. He'd never been a robust child, but he hadn't ever looked this pale and thin before. I stepped up and put my hand on his chest, felt the fluttering rhythm of his heart, racing fast, too fast beneath his soccer T-shirt. I glanced over at Zayvion, the person I trusted the least in the room. He gave me an innocent look, pulled a dollar out of his pocket and put it on the bar.

What do you know, he did have money.

Boy, the elder, poured him a cup of coffee. I figured Boy could take care of Zayvion if something went wrong.

"Call an ambulance, Mama. He needs a doctor."

"You Hound him first. See who does this to him," she said. "Then I call a doctor."

"Doctor first. Hounding won't do you or him any good if he's dead."

She scowled. I was not the kind of girl who panicked easily, and Mama knew it. And she also knew I had college learning behind me - or what I could remember of it, anyway.

"Boy," Mama yelled. Another of her sons, the one with a tight beard and ponytail, stepped out of the kitchen. "Call the doctor."

Boy picked up the phone and dialed.

"There," Mama said. "Happy? Now Hound him. Find out who wants to hurt him like this. Find out why anyone would hurt my boy."

I glanced at Zayvion again. He leaned against the wall, near the door, drinking his coffee. I didn't like Hounding in front of an audience, especially a stranger, but if this really was a magic hit, and not some sort of freak Disbursement-spell accident, then the user should be held accountable for Boy's doctor bills and recovery.

If he recovered.

I pressed my palm against Boy's chest and whispered a quick mantra. I didn't want to stretch myself to pull magic from outside the neighborhood. So, instead, I drew upon the magic from deep within my bones. My body felt strange and tight, like a muscle that hadn't been used in a while, but it didn't hurt to draw the magic forward. Four years in college had taught me that magic was best accessed when the user was close to a naturally occurring resource, like the natural cisterns beneath the west, east and south side of the city, or at an iron-and-glass-caged harvesting station or through the citywide pipelines.

What Harvard hadn't taught me was that I could, with practice, hold a small amount of magic in my body, and that other people could not. People who had tried to use their own bodies to contain magic ended up in the hospital with gangrenous wounds and organ failure.

But to me, holding a little magic of my own felt natural, normal. I couldn't remember a time when I didn't have the deep, warm weight of small magic inside me. When I was six I'd asked my mother about it. She told me people couldn't hold magic like that. I believed her. But she was wrong.

I whispered a spell to shape the warm, tingling sense of magic up into my eyes, my ears, my nose, and wove a simple glyph in the air with my fingertips. Like turning on a light in a dark room, the spell enhanced my senses and my awareness of magic.

No wonder the stink of old magic was so heavy in the room. The spell that was wrapped around Boy was violently strong, created to channel an extreme amount of magic. Instead of a common spell glyph that looked like fine lacework, this monster was made out of ropes as thick as my thumb. The magic knotted and twisted around Boy's chest in double-back loops - an Offload pattern. This spell was created to transfer the price of using magic onto an innocent - in this case, a five-year-old innocent. It was the kind of hit that would cause an adult victim's health to falter, or maybe they'd go blind for a couple months until the original caster's use of magic was absolved and the lines of magic faded to dust.

This was no accident.

Someone had purposely tried to kill this kid.

That someone had set an illegal Offloaded bothered me. That they had aimed it at a child made me furious.

The Offload pattern snaked up around Boy's throat like a fancy necklace, with extra chains that slipped down his nostrils. I could hear the rattle of magic in his lungs. No wonder the poor thing's heart was beating so fast.

I leaned in and sniffed at his mouth. The magic was old and fetid and smelled of spoiled flesh. A fresh hit never smelled that bad that fast. Boy hadn't been hit today. He probably hadn't even been hit yesterday. I realized, with a shock, that the little guy had been tagged a week ago, maybe more.

I didn't know how he had hung on so long.

I resisted the urge to lick at the magic, resisted the urge to place my lips briefly against the ropes that covered his mouth. Taste and smell were a Hound's strengths, and I could learn a lot about a hit by using them. But no one wanted to see a grown woman lick someone's wounds - magical or not. I took another deep breath, mouth open, to get the taste of the magic on my pallet and sinuses at the same time. The lines were so old, all I could smell was death. Boy's death.

I muttered another mantra, pulled a little more magic, and traced the cords across his chest with my fingers, memorizing the twists and knots and turns. Some of the smaller ropes lifted like tendrils of smoke - ashes from the Offload glyph's fire.

Every user of magic had their own signature - a style that was as permanent and unique as a fingerprint or DNA sequencing. A good Hand could forge the signature of a caster, but the forgery was never perfect, and rarely good enough to fool a Hound worth their salt.

And I was worth a sea of salt. I retraced the spell, lingered over knots and memorized where ropes crossed and parted and dissolved into one another.

I knew this mark. Knew this signature. Intimately.

I jerked my hand away from Boy, breaking the magical contact with him. No wonder the signature was familiar. It was my father's.

Copyright © 2008 by Devon Monk

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details