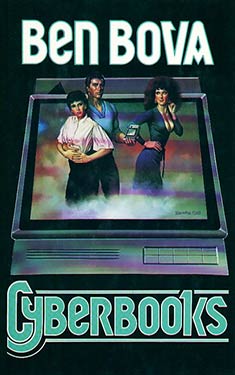

Cyberbooks

| Author: | Ben Bova |

| Publisher: |

Severn House, 1990 Tor, 1989 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Computer genius Carl Lewis has invented the "Cyberbook", an electronic device that instantly and inexpensively brings the written word to the masses. But not everyone warms to Carl's ideas. Add corporate spies, authors threatening to strike, and a wave of mysterious murders, and you have Ben Bova at his best.

Excerpt

MURDER ONE

The first murder took place in a driving April rainstorm, at the corner of Twenty-first Street and Gramercy Park West.

Mrs. Agatha Marple, eighty-three years of age, came tottering uncertainly down the brownstone steps of her town house, the wind tugging at her ancient red umbrella. She had telephoned for a taxi to take her downtown to meet her nephew for lunch, as she had every Monday afternoon for the past fourteen years.

The Yellow Cab was waiting at the curb, its driver imperturbably watching the old lady struggle with the wind and her umbrella from the dry comfort of his armored seat behind the bulletproof partition that separated him from the potential homicidal maniacs who were his customers. The meter was humming to itself, a sound that counterbalanced nicely the drumming of rain on the cab's roof; the fare was already well past ten dollars. He had punched the destination into the cab's guidance computer: Webb Press, just off Washington Square. A lousy five-minute drive; the computer, estimating the traffic at this time of day and the weather conditions, predicted the fare would be no more than forty-nine fifty.

Briefly he thought about taking the old bat for the scenic tour along the river; plenty of traffic there to slow them down and run up the meter. Manny at the garage had bypassed the automated alarm systems in all the cab's meters, so the fares never knew when the drivers deviated from the computer's optimum guidance calculations. But this old bitch was too smart for that; she would refuse to pay and insist on complaining to the hack bureau on the two-way. He had driven her before, and she was no fool, despite her age. She was a lousy tipper, too.

She finally got to the cab and tried to close the umbrella and open the door at the same time. The driver grinned to himself. One of his little revenges on the human race: keep the doors locked until after they try to get in. They break their fingernails, at least. One guy sprained his wrist so bad he had to go to the hospital.

Finally the cabbie pecked the touchpad that unlocked the right rear door. It flew open and nearly knocked the old broad on her backside. A gust of wet wind flapped her gray old raincoat.

"Hey, c'mon, you're gettin' rain inside my cab," the driver hollered into his intercom microphone.

Before the old lady could reply, a man in a dark blue trenchcoat and matching fedora pulled down low over his face splashed through the curbside puddles and grabbed for the door.

"I'm in a hurry," he muttered, trying to push the old woman out of the taxi's doorway.

"How dare you!" cried Mrs. Marple, with righteous anger.

"Go find a garbage can to pick in," snarled the man, and he twisted Mrs. Marple's hand off the door handle.

She yelped with pain, then swatted at the man with her umbrella, ineffectually. The man blocked her feeble swing, yanked the umbrella out of her grasp, and knocked her to the pavement. She lay there in a puddle, rain pelting her, gasping for breath.

The man raised her red umbrella high over his head, grasping it in both his gloved hands. The old woman's eyes went wide, her mouth opened to scream but no sound came out. Then the man drove the umbrella smashingly into her chest like someone would pound a stake through a vampire's heart.

The old lady twitched once and then lay still, the umbrella sticking out of her withered chest like a sword. The man looked down at her, nodded once as if satisfied with his work, and then stalked away into the gray windswept rain.

True to the finest traditions of New York's hack drivers, the cabbie put his taxi in gear and drove away, leaving the old woman dead on the sidewalk. He never said a word about the incident to anyone.

ONE

It was a Hemingway kind of day: clean and bright and fine, sky achingly blue, sun warm enough to make a man sweat. A good day for facing the bulls or hunting rhino.

Carl Lewis was doing neither. In the air-conditioned comfort of the Amtrak Levitrain, he was fast asleep and dreaming of books that sang to their readers.

The noise of the train plunging into a long, dark tunnel startled him from his drowse. He had begun the ride that morning in Boston feeling excited, eager. But as the train glided almost silently along the New England countryside, levitated on its magnetic guideway, the warm sunshine of May streaming through the coach's window combined with the slight swaying motion almost hypnotically. Carl dozed off, only to be startled awake by the sudden roar of entering the tunnel.

His ears popped. The ride had seemed dreamily slow when it started, but now that he was actually approaching Penn Station it suddenly felt as if things were happening too fast. Carl felt a faint inner unease, a mounting nervousness, butterflies trembling in his middle. He put it down to the excitement of starting a new job, maybe a whole new career.

Now, as the train roared through the dark tunnel and his ears hurt with the change in air pressure, Carl realized that what he felt was not mere excitement. It was apprehension. Anxiety. Damned close to outright fear. He stared at the reflection of his face in the train window: clear of eye, firm of jaw, sandy hair neatly combed, crisp new shirt with its blue MIT necktie painted down its front, proper tweed jacket with the leather elbow patches. He looked exactly as a brilliant young software composer should look. Yet he felt like a scared little kid.

The darkness of the tunnel changed abruptly to the glaring lights of the station. The train glided toward a crowded platform, then screeched horrifyingly down the last few hundred yards of its journey on old-fashioned steel wheels that struck blazing sparks against old-fashioned steel rails. A lurch, a blinking of the light strips along the ceiling, and the train came to a halt.

With the hesitancy known only to New Englanders visiting Manhattan for the first time, Carl Lewis slid his garment bag from the rack over his seat and swung his courier case onto his shoulder. The other passengers pushed past him, muttering and grumbling their way off the train. They shoved Carl this way and that until he felt like a tumbleweed caught in a cattle stampede.

Welcome to New York, he said to himself as the stream of detraining passengers dumped him impersonally, indignantly, demeaningly, on the concrete platform.

The station was so big that Carl felt as if he had shrunk to the size of an insect. People elbowed and stamped their way through the throngs milling around; the huge cavern buzzed like a beehive. Carl felt tension in the air, the supercharged crackling high-stress electricity of the Big Apple. Panhandlers in their traditional grubby rags shambled along, each of them displaying the official city begging permit badge. Grimy bag ladies screamed insults at the empty air. Teenaged thugs in military fatigues eyed the crowds like predators looking for easy prey. Religious zealots in saffron robes, in severe black suits and string ties, even in mock space suits complete with bubble helmets, sought alms and converts. Mostly alms. Police robots stood immobile, like fat little blue fireplugs, while the tides of noisy, smelly, angry, scampering humanity flowed in every direction at once. The noise was a bedlam of a million individual voices acting out their private dramas. The station crackled with fierce, hostile anxiety.

Carl took a deep breath, clutched his garment bag tighter, and clamped his arm closely over the courier case hanging from his shoulder. He avoided other people's eyes almost as well as a native Manhattanite, and threaded his way through the throngs toward the taxi stand outside, successfully evading the evangelists, the beggars, the would-be muggers, and the flowing tide of perfectly ordinary citizens who would knock him down and mash him flat under their scurrying shoes if he so much as missed a single step.

There were no cabs, only a curbside line of complaining jostling men and women waiting for taxis. A robot dispatcher, not unlike the robot cops inside the station, stood impassively at the head of the line. While the police robots were blue, the taxi dispatcher's aluminum skin was anodized yellow, faded and chipped, spattered here and there with mud and other substances Carl preferred not to think about.

Every few minutes a taxi swerved around the corner on two wheels and pulled up to the dispatcher's post with a squeal of brakes. One person would get in and the line would inch forward. Finally Carl was at the head of the line.

"I beg your pardon, sir. Are you going uptown or downtown?" asked the man behind Carl.

"Uh, uptown--no, downtown." Carl had to think about Manhattan's geography.

"Excellent! Would you mind if I shared a cab with you? I'm late for an important appointment. I'll pay the entire fare."

The man was tiny, much shorter than Carl, and quite slim. He was the kind of delicate middle-aged man for whom the word dapper had been coined. He wore a conservative silver-gray business suit; the tie painted down the front of his shirt looked hand done and expensive. He was carrying a blue trenchcoat over one arm despite the gloriously sunny spring morning. Silver-gray hair clipped short, a toothy smile that seemed a bit forced on his round, wrinkled face. Prominent ears, watery brownish eyes. He appeared harmless enough.

The big brown eyes were pleading silently. Carl did not know how to refuse. "Uh, yeah, sure, okay."

"Oh, thank you! I'm late already." The man glanced at his wristwatch, then stared down the street as if he could make a cab appear by sheer willpower.

A taxi finally did come, and they both got into it.

"Bunker Books," said Carl.

The taxi driver said something that sounded like Chinese. Or maybe Sanskrit.

"Fifth Avenue and Eighth Street," said Carl's companion, very slowly and loudly. "The Synthoil Tower."

The cabbie muttered to himself and punched the address into his dashboard computer. The electronic map on the taxi's control board showed a route in bright green that seemed direct enough. Carl sat back and tried to relax.

But that was impossible. He was sitting in a Manhattan taxicab with a total stranger who obviously knew the city well. Carl looked out the window on his side of the cab. The sheer emotional energy level out there in the streets was incredible. Manhattan vibrated. It hummed and crackled with tension and excitement. It made Boston seem like a placid country retreat. Hordes of people swarmed along the sidewalks and streamed across every intersection. Taxis by the hundreds weaved through the traffic like an endless yellow snake, writhing and coiling around the big blue steam buses that huffed and chuffed along the broad avenue.

The women walking along the sidewalks were very different from Boston women. Their clothes were the absolutely latest style, tiny hip-hugging skirts and high leather boots, leather motorcycle jackets heavy with chains and lovingly contrived sweat stains. Most of the women wore their biker helmets with the visor down, a protection against mugging and smog as well as the latest fashion. The helmets had radios built into them, Carl guessed, from the small whip antennas bobbing up from them. A few women went boldly bareheaded, exposing their long hair and lovely faces to Carl's rapt gaze.

The cab stopped for a red light and a swarm of earnest-looking men and women boiled out of the crowd on the sidewalk to begin washing the windshield, polishing the grillwork, waxing the fenders. Strangely, they wore well-pressed business suits and starched formal shirts with corporate logos on their painted ties. The taxi driver screamed at them through his closed windows, but they ignored his Asian imprecations and, just as the light turned green again, affixed a green sticker to the lower left-hand corner of the windshield.

"Unemployed executives," explained Carl's companion, "thrown out of work by automation in their offices."

"Washing cars at street corners?" Carl marveled.

"It's a form of unemployment benefit. The city allows them to earn money this way, rather than paying them a dole. They each get a franchise at a specific street corner, and the cabbie must pay their charge or lose his license."

Carl shook his head in wonderment. In Boston you just stood in line all day for a welfare check.

"Bunker Books," mused his companion. "What a coincidence."

Carl turned his attention to the gray-haired man sitting beside him.

"Imagine the statistical chance that two people standing next to one another in line waiting for a taxi would have the same destination," the dapper older man said.

"You're going to Bunker Books, too?" Carl could not hide his surprise.

"To the same address," said the older man. "My destination is in the same building: the Synthoil Tower." He glanced worriedly at the gleaming gold band of his wristwatch. "And if we don't get through this traffic I am going to be late for a very important appointment."

The taxi driver apparently could hear their every word despite the bulletproof partition between him and the rear seat. He hunched over his wheel, muttering in some foreign language, and lurched the cab across an intersection despite a clearly red traffic light and the shrill whistling of a brown-uniformed auxiliary traffic policewoman. They swerved around an oncoming delivery truck and scattered half a dozen pedestrians scampering across the intersection. Carl and his companion were tossed against one another on the backseat. The man's blue trenchcoat slid to the filthy floor of the cab with an odd thunking sound.

"Who's your appointment with?" Carl asked, inwardly surprised at questioning a total stranger so brazenly--and with poor grammar, at that.

The older man seemed unperturbed by either gaffe as he retrieved his trenchcoat. "Tarantula Enterprises, Limited. Among other things, Tarantula owns Webb Press, a competitor of Bunker's, I should think."

Carl shrugged. "I don't know much about the publishing business...."

"Ahh. You must be a writer."

"Nosir. I'm a software composer."

The rabbity older man made a puzzled frown. "You're in the clothing business?"

"I'm a computer engineer. I design software programs."

"Computers! That is interesting. Is Bunker revamping its inventory control system? Or its royalty accounting system?"

With a shake of his head, Carl replied, "Something completely different."

"Oh?"

In all of Carl's many telephone conversations with his one friend at Bunker Books a single point had been emphasized over and over. Tell no one about this project,the woman had whispered urgently. Whispered, as though they were standing in a crowded room rather than speaking through a scrambled, private, secure fiberoptic link. If word about this gets out to the industry--don't say a word to anybody!

"It's, uh, got to do with the editorial side of the business," he generalized.

"I see," said his companion, smiling toothily. "A computer program to replace editors. Not a very difficult task, I should imagine."

Stung to his professional core, Carl replied before he could think of what he was saying, "Nothing like that! There've been editing programs for twenty years, just about. Using a computer to edit manuscripts is easy. You don't need a human being to edit a manuscript."

"So? And what you are going to do is difficult?"

"Nobody's done it before."

"But you will succeed where others have failed?"

"Nobody's even tried to do this before," Carl said, with some pride.

"I wonder what it could be?"

Carl forced himself to remain silent, despite the voice inside his head urging him to reach into the courier case lying on the seat between them and pull out the marvel that he was bringing to Bunker Books. A slim case of plastic and metal, about the size of a paperback novel. With a display screen on its face that could show any page of any book in the history of printing. The first prototype of the electronic book. Carl's very own invention. His offspring, the pride of his genius.

The taxi lurched around a corner, then stopped so hard that Carl was thrown almost against the heavy steel-and-glass partition. His companion seemed to hold his place better, almost as if he had braced himself in advance. His trenchcoat flopped over Carl's courier bag with a heavy thunking sound that was lost in the squeal of the taxi's brakes.

"Synthoil Tower," announced the cab driver. "That's eighty-two even, with th' tip."

True to his word, the dapper gray-haired man slid his credit card into the slot in the bulletproof partition, patted Carl's arm briefly by way of farewell, then scampered to the imposing glass-and-bronze doors of the Synthoil building. It took a few moments for Carl to gather his two bags and extricate himself from the backseat of the taxi. The cabbie drummed his fingers on his steering wheel impatiently. As soon as Carl was clear of the cab, the driver pulled away from the curb, the rear door swinging shut with a heavy slam.

Carl gaped at the rapidly disappearing taxi. For a wild instant a flash of panic surged through him. Clutching at his courier case, though, he felt the comforting solidity of his prototype. It was still there, safely inside his case.

So he thought.

Reader's Report

Title: The Terror from Beyond Hell

Author: Sheldon Stoker

Category: Blockbuster horror

Reader: Priscilla Alice Symmonds

Synopsis: What's to synopsize? Still yet another trashy piece of horror that will sell a million copies hardcover. Stoker is awful, but he sells books.

Recommendation: Hold our noses and buy it.

TWO

Lori Tashkajian's almond-shaped eyes were filled with tears. She was sitting at her desk in the cubbyhole that passed for an editor's office at Bunker Books, staring out the half window at the slowly disappearing view of the stately Chrysler Building.

Her tiny office was awash with paper. Manuscripts lay everywhere, some of them stacked in professional gray cartons with the printed labels of literary agents affixed to them, others in battered cardboard boxes that had once contained shoes or typing paper or even children's toys. Still others sat unboxed, thick wads of paper bound by sturdy elastic bands. Everywhere. On Lori's desk, stuffing the bookshelves along the cheap plastic partition that divided the window and separated her cubicle from the next, strewn across the floor between the partition and gray metal desk, piled high along the window ledge.

One of management's strict edicts at Bunker Books was that editors were not allowed to read on the job. "Reading is done by readers," said the faded memo tacked to the wall above Lori's desk. "Readers are paid to read. Editors are paid to package books that readers have read. If an editor finds it necessary to read a manuscript, it is the editor's responsibility to do the reading on her or his own time. Office hours are much too valuable to be wasted in reading manuscripts."

Not that she had time for reading, anyway. Lori ignored all the piled-up manuscripts and, sighing, watched the construction crew weld another I-beam into the steel skeleton that was growing like Jack's beanstalk between her window and her view of the distinctive art-deco spike of the Chrysler Building. In another week they would blot out the view altogether. The one beautiful thing in her daily grind was being taken away from her, inches at a time, erased from her sight even while she watched. Coming to New York had been a mistake. Her glamorous life in the publishing industry was a dead end; there were no men she would consider dating more than once; and now they were even taking the Chrysler Building away from her.

She was a strikingly comely young woman, with the finely chiseled aquiline nose, the flaring cheekbones, the full lips, the dark almond eyes and lustrous black hair of distant romantic desert lands. Her figure was a trifle lush for modern New York tastes, a touch too much bosom and hips for the vassals of Seventh Avenue and their cadaverous models. Her life was a constant struggle against junk food. Instead of this week's fashionable biker image, which would have made her look even more padded than she was naturally, Lori wore a simple sweater and denim skirt.

She sighed again, deeply. There was nothing left except the novel, and no one would publish it. Unless...

The novel. It was a work of pure art, and therefore would be totally rejected by the editorial board. Unless she could gain a position of power for herself. If only Carl...

The desk phone chimed. Lori blinked away her tears and said softly, "Answer answer." The command to the phone had to be given twice, as a precaution against setting off its voice-actuated computer during the course of a normal conversation.

"A Mr. Lewis to see you," said the phone. "He claims he has an appointment." Whoever had programmed the communications computer had built in the hard-nosed suspicion of the true New Yorker. Even its voice sounded nasty and nasal.

"Show him in," commanded Lori. Softly. On second thought she added, "No, wait. I'll come out and get him."

Carl could be the answer to all her problems. He was brilliant. His invention could propel Bunker Books to the top of the industry. And, having dated him more than once in Boston, Lori was willing to try for more. But Carl would never find his way through this rabbit warren of offices and corridors, Lori told herself as she made the three steps it took to get through the only clear path between her desk and her door. Carl could design electronic software that made MIT professors blink with pleasured surprise, but he got lost trying to cross the street. She hurried down the narrow corridor toward the reception area.

Sure enough, Carl stood blinking uncertainly at the first cross-hallway, trying to figure out the computer display screen on the wall that supposedly showed even the most obtuse visitor the precise directions to the office he or she was seeking. True to his engineering nature, Carl was peering at the wall fixture with its complex code of colored paths rather than asking any of the people scurrying along the corridors.

He looked exactly as she remembered him: tall, trim, handsome in a boyish sort of way. He carried a garment bag and a smaller one both slung over the same shoulder, rumpling his tweed jacket unmercifully and making him look like an ill-clothed hunchback.

"Carl! Hi!"

He looked up toward Lori, blinked, and his smile of recognition sent a thrill through her.

"Hi yourself," he replied, just as he had in the old days when they had both been students: he at MIT and she at Boston University.

Carl put out his right hand toward her, and Lori took it in hers. Instead of a businesslike handshake she stepped close enough to peck at his cheek in the traditional gushy, phony manner of the publishing industry. But the heavy bags started to slip off Carl's shoulder and somehow wrapped themselves around her. Lori found herself pressed against Carl, and the traditional peck became a full, warm-blooded kiss on his lips. Definitely not phony, at least on her part.

Somebody snickered. She heard a wolf whistle from down the hall. As they untangled, she saw that Carl's face was red as a May Day banner. She felt flustered herself.

"I... I'm sorry," Carl stammered, trying to straighten out the twisted shoulder straps of his bags.

Lori smiled and said nothing. She took him by the free arm and led him back toward her office.

"Did you bring it?" she asked as they strode down the corridor. It was barely wide enough for the two of them to pass through side by side. Lori had to press close to his tweed-sleeved arm.

He nodded. "It's right here."

"Wonderful."

As she pushed open the door to her cubbyhole, Lori's heart sank. It was such a tiny office, so shabby, so sloppy with all those damned manuscripts all over the place, schedules and cover proofs tacked to the walls. It seemed even smaller with Carl in it; he looked like a giant wading through a sea of paper.

But he said, "Wow, you've got an office all to yourself!"

"It's a little on the small side," she replied.

"I'm still sharing that telephone booth with Thompson and two freshmen."

Lori had not the slightest doubt that Carl was being sincere. There was not a dissembling bone in his body, she knew. That was his strength. And his weakness. She would have to protect him from the sharks and snakes, she knew.

"You can hang your garment bag on the back of the door," Lori told him as she picked a double armload of manuscripts off the only other chair in the office and plopped them onto the window ledge, atop the six dozen already there. What the hell, she thought. I can't see much out of the window now anyway.

"We don't have much time before the meeting starts," she said as she slid behind her desk and sat down.

"Meeting?" Carl felt alarmed. "What meeting? I thought--"

"The editorial board meeting. It's mandatory for all the editors. Every Tuesday and Thursday. Be there on time, or else. One of the silly rules around here."

Carl muttered, "I'm going to have to show this to your entire board of editors?"

Lori moved her shoulders in a semishrug that somehow stirred Carl's blood. He had not seen her in nearly two years; until just now he had not realized how much he had missed her.

"I wanted you to show it to me first," she was saying, "and then we'd go in and show the Boss. But now it's time for the drippy meeting, and I have to attend."

"It's my own fault," said Carl. "The train was late, and it took me longer to get a cab than I thought it would. I should have taken an earlier train."

"Can you show me how it works? Real quick, before the meeting starts?"

"Sure." Carl took the emptied chair and unzipped his courier case. From it he pulled a gray oblong box, about five inches by nine and less than an inch thick. Its front was almost entirely a dark display screen. There was a row of fingertip-sized touchpads beneath the screen.

"This is just the prototype," Carl said almost apologetically. "The production model will be slightly smaller, around four by seven, just about the size of a regular paperback book."

Lori nodded and reached out her hands to take the electronic book from its inventor.

The phone chimed. "Editorial board meeting starts in one minute," said the snappish computer voice. "All editors are required to attend."

With a sigh, Lori said, "Come on, you can show the whole editorial board."

"This'll only take a few seconds."

"I can't be late for the meeting. They count it against you when your next salary review comes up."

"They take attendance and mark you tardy?"

"You bet!"

Stuffing his invention back in the black case and getting to his feet, Carl said, "Sounds like kindergarten."

With a rueful smile, Lori agreed, "What do you mean, 'sounds like'?"

*

Twenty floors higher in the Synthoil Tower sprawled the offices of Webb Press, a wholly owned subsidiary of Tarantula Enterprises (Ltd.). The reception area was larger than the entire set of grubby editorial cubicles down at Bunker Books. Sweeping picture windows looked out on the majestic panorama of lower Manhattan: the financial district, the twin Trade Towers, the magnificent new Disneydome that covered most of what had once been the slums and tenements of the Lower East Side. Farther away stood the Statue of Liberty and the sparkling harbor.

Harold D. Lapin sat patiently on one of the many deep soft leather chairs arranged tastefully across the richly soft silk carpeting of the reception area. His blue trenchcoat lay neatly folded across the chair's gleaming chrome arm. Being the man he was, Lapin's interest was focused not on the stunningly beautiful red-haired receptionist sitting behind her glass desk, microskirted legs demurely crossed, nor even on the splendid view to be seen through the picture windows. Rather, he studied the intricate floral pattern of the heavy drapes that framed the windows, mentally tracing a path from the ceiling to the floor that did not cross a flower, leaf, or stem.

"Mr. Lapin?" came the dulcet tones of the receptionist.

He turned in his chair to look at her, and she smiled a practiced smile that suggested much and revealed nothing.

"Mr. Hawks will see you now."

As she spoke, a door to one side of her desk slid open soundlessly and an equally lovely woman appeared there. She nodded slightly. Like the receptionist she was red of hair, gorgeous of face and figure, and dressed in the microskirt and tailored blouse that seemed to be something of a uniform at Webb Press.

Lapin followed the young woman wordlessly along broad quiet corridors lined with exquisite paintings and an occasional fine small bronze on a pedestal. All the doors along the corridor were tightly closed; the brass nameplates on them were small, discreet, tasteful.

Power exuded from those doors. Lapin could feel it. There was money here, much money, and the power to do great things.

At the end of the corridor was a double door of solid oak bearing an equally simple nameplate: P. Curtis Hawks. Idly wondering what the "P." stood for, and why Hawks preferred his second name to his first, Lapin allowed himself to be ushered through the double doors, past a phalanx of desks and secretaries (all red-haired), into an inner anteroom where still another gorgeous red-haired young woman smiled up at him and gestured silently toward the unmarked door beyond her airport-sized desk.

Are they all mute? Lapin wondered. Does Hawks clone them, all these redheads?

The unmarked door opened of itself and Lapin stepped through. The sanctum sanctorum inside was somewhat smaller than he had imagined it would be, merely the size of a bus terminal or a minor cathedral. It was splendidly paneled in teak, however, and its floor-length windows opened onto a handsome terrace that looked out on the East River, the Brooklyn condo complex, and the slender grace of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. A massive teak desk took up one end of the room, its broad clean top supported by four carved elephants with real ivory tusks. The other corners of the huge office contained, respectively, a conference table that could seat twelve, an electronics center that rivaled anything in Cape Canaveral, and a billiard table with an ornate Tiffany lamp hanging above it.

Hawks was standing by the French windows, fists clenched together behind his back, with the morning sun streaming in so boldly that it made Lapin's eyes water to gaze upon the president of Webb Press.

"Well?" Hawks snapped, without turning to face his visitor.

Squinting somewhat painfully, Lapin said, "Mission accomplished, sir." He had been told by the man who had hired him that Hawks preferred military idioms.

Hawks spun around and clapped his hands together with a loud smack. "Good! Let's see what you got."

P. Curtis Hawks was a short, chubby man in his late fifties. His curly red hair was obviously a toupee, to Lapin's refined eye. Hawks's face was round, puffy-cheeked, with eyes so small and set so deep beneath menacing russet brows that Lapin could not tell what color they were. The man had a plastic pacifier clamped between his teeth; it was colored brown and shaped like a cigar butt. He wore a sky-blue suit tailored to suggest a military uniform: epaulets, decorative ribbons over the left breast pocket, trousers creased to a razor's edge. Yet he did not look military; he looked like a beach ball that had been unexpectedly drafted.

Hawks gestured to the electronics center. Lapin placed his trenchcoat neatly on the back of one of the six chrome chairs there, and slid an oblong black box from the coat's inner pocket.

"You know how to work a scanner?" Hawks growled. His voice was like a diesel engine's heavy rumbling, yet there was a trace of a whine in it.

"Yessir, of course," said Lapin. Without sitting, he slid his black box into a slot on the console, then studied the control keyboard for a brief moment.

Hawks paced back and forth and chewed on his pacifier. "Three-D X rays," he muttered. "Do you realize that with this one hologram we'll be able to save the corporation the trouble of buying out those assholes at Bunker Books?"

Tapping commands into the console, Lapin replied absently, "I had no idea so much was at stake." Then he found himself adding, "Sir."

"There's billions involved here. Billions."

The display screen before the two standing men glowed to life, and a three-dimensional picture took form.

"What in hell is that?" Hawks shouted.

Lapin gasped in sudden fear. Hanging in midair before his horrified eyes was a miniature three-dimensional picture of what appeared to be the rear axle of a New York taxicab, overlain with vague blurs of other things.

"You shitfaced asshole!" Hawks screamed. "You used too much power! The X rays went right through his goddamned device and took a picture of the goddamn cab's axle! I'll have you broken for this!"

Copyright © 1989 by Ben Bova

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details