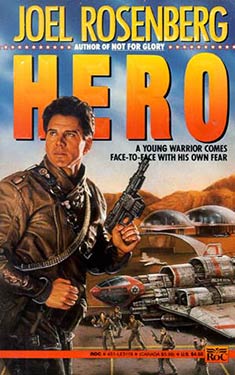

Hero

| Author: | Joel Rosenberg |

| Publisher: |

Roc, 1990 |

| Series: | Metzada Mercenary Corps: Book 4 |

|

1. Ties of Blood and Silver |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Metzada is an inhospitable planet of Epsilon Indi whose inhabitants -- most descendants from refugees forced to leave Israel -- can survive only because its men are highly skilled mercenaries, Metzada's one export that brings in revenue. When young Ari Hanavi freezes in combat twice, he has one last chance to survive and even become a "hero". Scenes of battle, military command and operations are expertly portrayed in this novel about a young man who must overcome his terror while dealing with his fellow soldiers and fighting an enemy force.

Set in the same world as Not for Glroy, which David Drake called "a swift-paced, brutal, excellent political novel about the soldier of the future".

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

Spare Parts

He was a spare part, newly machined and shoved into a place where he didn't quite fit, where he never would fit.

The cargo bay stank of plastics and oil and sweat and his own fear. Ari Hanavi tried to keep his trembling under control as the skipshuttle took another lurch. Gripping the arms of the acceleration frame helped, but only a little. He shifted a centimeter or so to his left, as though huddling up against the smoothly curving wall could offer some protection.

It couldn't. Not to him, and not to more than seven hundred other men crammed into two decks in the cargo bay of the skipshuttle, packed tightly into rows of acceleration frames divided by the same kind of steel that divided the lower deck from the upper, all divided from the screaming air outside by only a few thin layers of titanium aluminide.

Ari couldn't stop thinking about how thin those layers were.

Beyond Benyamin's acc frame, Yitzhak Slepak grumbled something. Ari didn't pay him much attention, although, packed in as tightly as they were, he probably could have made out his words despite the noise. Slepak was only a couple of thousand hours older than Ari, but he tried to act like it was years. He was always grumbling about something, probably trying to sound like a man instead of a virgin.

Some of the men complained a lot. It helped, they said.

It wouldn't have helped Ari any. All it would have done was remind Benyamin and the other three that he wasn't experienced. He wasn't even a PFC. He was just a very green private, a seventeen-year-old virgin, and he didn't fit in, he'd never fit.

There was something that the rest of them didn't know, not yet: Ari Hanavi was a coward.

If they knew, everybody he loved would turn against him.

No, not if. When they knew....

His brothers, both of his mothers, the Sergeant, even Miriam. If they found out. When they found out.

But maybe not yet. Please, not yet.

The whine of the outside air got louder, now easily loud enough to drown out casual conversation. Ari tried to force himself to relax.

The Nueva Terra job was just going to be cadre, he told himself, the regiment configured for training, the platoon Ari was a very junior member of acting as a mainly token security element. It was likely he would spend most of his time standing guard duty at a Casalingpaesan training facility a thousand klicks from the war zone while the regiment turned Casa virgins into soldiers.

At best, he would have some time off on a new world while the senior staff took the trained and tuned Casa division into the field. At worst, the RHQ security platoon would accompany Division HQ into the field, and perhaps Ari would have to help his brother debrief a returning Casalingpaesan patrol or two. More likely, he would just help teach some Casalinguese to do it.

Easiest thing in the world. No courage needed, no warrior's reflex required.

Please.

Benyamin muttered something; Ari couldn't quite make it out. Ari's fingers were groping at the air under his chin where his mike should have been before he remembered that he wasn't wearing his headset. The captain of the skipshuttle didn't want any RF interference--much less the seemingly random spurts of packed and coded packets--from inside the skip-shuttle: all their comm gear was stowed away in their chestpacks.

"Say again?"

"Relax," Benyamin said. "It'll be okay."

That was what his big brother was always saying, and when he wasn't saying it, he was making it so.

It wasn't just that Benyamin was fifteen years older than Ari, although that made a difference. It wasn't just his size: Benyamin was actually a centimeter shorter than Ari's 176 and only a bit thicker, massing about ninety-five kilograms to Ari's eighty-five--but Ari always thought of him as a giant of a man, even when he stood next to Dov.

Benyamin wasn't just his big brother, he was the big brother, forty days older than Kiyoshi had been. They all said that Ari looked like a younger version of Benyamin, but that was nonsense. There was a lot of nonsense that was passed around the family. Like the way that the other boys called Ari "the General," as if he'd be an officer some day.

It was all stupid. Ari didn't look anything like his big brother. Benyamin's jaw was firm, his head covered with tight curls of brown hair, his gaze level and even. Ari shook all the time. While Ari couldn't even move the tight grimace that his face had become, the smile that covered Benyamin's pleasantly ugly face was warm, even in the harsh green light of the overhead glows.

As Tetsuo always said, Benyamin's smile didn't have anything to do with "an emotion; that smile was a report. It said: I'll handle it, I'll take care of it. I've got it all under control, don't worry for a moment.

How can you take care of your little brother being a gutless coward?

There was no way out.

Ari shifted fractionally in his acc frame, held there more by the straps than by what little weight there was. He couldn't do more than twitch: there was no real back to what would have been a couch or chair in a civvy skipshuttle. What would have been the frame for a seat cushion was built differently, to hold his loosened buttpack; another steel frame, replacing the back of the seat, supported his backpack.

All of them were like that, held into their little niches like a set of specialized tools in a preformed case. Which was, in a sense, what they were.

Lots of them were spare parts, sometimes new, sometimes cannibalized from other units. Benyamin, Alon, Laskov, Lavon, Lavinsky had all been in the old Fifth Regiment, under Becker. The regiment had been cut to pieces on Kinshasakisasa, then cut to pieces after Kinshasakisasa, its colors retired, the survivors shuffled into other sections, platoons, companies, battalions and regiments.

The skipshuttle screamed as they descended, 750 men and virgins packed into a crowded, smelly space that would have been tight for half that many.

Some were taking the ride a lot more casually than Ari was; the soldier in the acc frame directly above him was patiently drumming his bootheels against the footrests. By the TO, it should have been Pinhas Gevat, Kelev One Two Four Five, Ari's equivalent in Section Two and one of the other five Kelev virgins--but half the time you didn't get the right spot. Ari's fireteam had been split up; he and Benyamin were two rows away from Laskov, Lavon and Lavinsky.

He pumped first his right leg, then his left, trying to keep from getting cramps. Ari had good Metzadan circulation, but his blood tended to pool in his chest and head in zero gee. Like the low-gee acne speckling his face, the cramps were a common complaint. He had learned in school and in training that both would go away after he was down--the cramps within a day or two; the acne within a week or so.

He rubbed at his face. Nothing to be done about the acne. A brisk sprint on a running ring would prevent the cramps--that was what he had done on the troopship--but there wasn't room in the skipshuttle even to swing a knife.

His rifle was clamped across his lap, holding it and him in place. His hands fell to the clamps, fingers resting lightly on the cold aluminum. It would only take two quick pulls to release it, and he had never liked being held down. Back when he was a boy, wrestling with his brothers, that had been the way they could always make him furious: just pin him down and hold him. If he didn't concentrate he would panic, he would lose control and--

No. Stop it. He forced himself to breathe slower, to at least simulate relaxing. There was nowhere to go. What could he do? Rattle around between Benyamin and the wall, or bounce up and down between his acc frame and the one above him?

His right hand, as though of its own volition, came up to his backpack's release, right over the sternum, just under the swell of his chestpack, while his left fell to the release of his buttpack. Two quick pulls and he would be free.

It would be good to be free.

Benyamin caught the movement and his smile broadened. "Really," he shouted over the almost deafening roar. "Everything will be fine."

He was right, of course. If anything went wrong, there was nothing they could do. Which was why they were all clamped in tight and were supposed to just sit still. It only stood to reason.

If only his palms would listen to reason; the grips of his acc frame were sweat-slick.

"Hey, come on." Benyamin smiled. "Would you rather be here in the first shuttle, or waiting up in zero gee with the other two loads?"

Ari shrugged. He really didn't mind zero gee.

"Relax," Benyamin, said. "If something were to happen," he shouted, "at, say, Mach 5--I said, if we take a glancing hit from some local artillery--we'd be dead, spread over the sky, before we even felt it."

That was supposed to reassure Ari. Benyamin was like that. Ari had more than a sneaking suspicion that despite Ari's supposedly better training, Benyamin's six campaigns had taught him that the possibility of sudden death was reassuring. Or maybe it was the series of four puckered scars that ran from his fused right wrist and up that arm, almost to the elbow. Benyamin had never told him how he got those. The only thing he would say was that there was nothing that Ari could learn from it because not being a damn fool is something you had to learn for yourself. He--

The lights went out.

A few rows behind him somebody screamed, and the scream became a chorus of hoarse shouts.

Ari Hanavi clamped his hands around the stock of his Barak assault rifle, shut his eyes tightly and waited to die.

"Tel Aviv Ten. Ease up,all of you." Colonel Peled's crisp, cold voice, broadcast over the wall speaker high above Ari's head, cut through the shouts and the cries. "It's just the fucking lights."

Even in cadre regiments, Metzada generally tries to get the most out of its senior field grade officers, and Shimon Bar-El worked that tradition hard: Peled was the regimental chief of staff and deputy commander, mainly responsible for running the company-sized Support/Transport/Medical Command. He had been with Uncle Shimon even longer than Galil had, although not as long as Dov and Avram.

Nobody had been with Shimon as long as Dov and Avram.

"There's no need to be loud, Mordecai." Shimon Bar-El's voice was dry and distant over the speakers, its lazy calmness reassuring. "After all, there were no shouts just now. I am not going to believe that Metzadan soldiers are afraid of the dark. And the Casas aren't paying us for screams," he said.

"Not ours," Captain Yitzhak Galil said with a boyish laugh. "Shit, if I got paid for every time I screamed, I'd have retired ten years ago."

"Fifteen-year-olds don't retire," Bar-El said.

The other two laughed, joining in on the weak joke. The general, his chief of staff and the commander of the regimental HQ company were a well-polished comedy act, and their routines had been refined by frequent use. Or overuse.

The noisy whine of the outside air intensified even further as their weight started to press them down.

The lights flickered on for a moment, then dimmed.

"Just what we need," Benyamin said. "A funny RHQ company commander."

In front of Ari, Tzvi Hirshfield leaned his head back against the mesh to talk to Benyamin. "Hey, remember the time on Rand? Back when he'd just made sergeant in the Fifth?"

"With the jecty and the goat? Yeah. Asshole."

Hirshfield shrugged. "Well, I thought it was funny."

"You would."

The lights went out again, then came back on. This time there were no shouts, only the scream of the air outside.

Ari leaned toward Benyamin. "I thought you said Galil's good."

"When there're shots going off, he's supposed to be pretty good." His brother shrugged. "But I can get real tired of this shit in garrison."

Which is where they were going to be for the foreseeable future. Cadre work is, by definition and in practice, garrison work.

"Now, martinets aren't too bad," Benyamin went on, warming to the subject. "I can take a martinet; they're predictable and--"

"You can take a martinet? Bullshit." Hirshfield grunted. "Tell that to Simchoni."

"Simchoni? A bit strict, maybe, but I wouldn't call him a martinet."

"Not Ezra. Sol."

"That shithead." Benyamin scowled, then shrugged. "Rest in peace."

A passenger skipshuttle would have had an accelerometer mounted high on the forward bulkhead for the convenience and relief of passengers, so they could see that their weight was only returning, not growing and growing....

Watching the accelerometer was supposed to control the sense of panic you get when your stomach tells you that you're getting more weight than you're supposed to. Then again, a passenger skipshuttle probably wouldn't have hit even two gees for a Nueva Terra landing. Ari was sure they were hitting four--better than three times the grav on Metzada. Like having three of his brothers sitting on his shoulders and chest.

Benyamin's chuckle sounded forced as the lights flickered and then came back on, while their weight began to ease. "Told you it was nothing," he said.

Beyond him, Yitzhak Slepak grunted. "Wonder if that was the pilot having a bit of fun with us," he said. "I might look him up later."

"Shut up," Benyamin said, strangely without heat.

If Ari had mouthed off like that, Benyamin would have been jumping up and down on him, perhaps literally, but ever since the regiment had boarded the skipshuttle on Rand, he had noticed that the men treated Yitzhak and a few other boys more gently than most of the virgins.

Didn't make any sense, but Ari didn't ask about it and they didn't talk about it. One of the first things they taught you was that you'd usually be told what you need to know, and when you needed to know it. Questions weren't really discouraged--but they had better be pertinent.

Benyamin bit his lip, considering, as the roar of the skipshuttle started to lessen. "Final approach; the grav feels about right."

"You sure?"

Benyamin didn't smile. "No. I don't have that kind of feel. Dov would know. Want me to get up and ask him?"

Ari didn't answer. Dov Ginsberg frightened him, a lot, and he was sure he had only heard some of the stories.

"Tel Aviv Ten. We are three minutes from touchdown." Peled's voice, businesslike as always, came over the speaker. Peled couldn't talk over a comm system without coming down hard on at least one word every sentence; Ari could never quite figure which word it would be. "Estimate of fifteen minutes rollout and cooldown before they unlock us--and for those of you who have forgotten, that means the heat shields will still be hot. You section leaders will keep your people the hell away from the skin. Support/ Transport Command will deploy administrative, repeat administrative--and keep cool, people. In case anybody's memory is slipping or their fingers are getting itchy, this is not, repeat not,a hot LZ, and we will not have any accidents."

"Exactly right." Uncle Shimon's voice came on in quiet counterpoint. "Headquarters is administrative; all of Regimental HQ Company is operational--not just Kelev."

Ari didn't understand the reason for that, although he didn't mind. It meant that the headquarters security force, call sign Kelev, would get priority for getting off the bus to Camp Ramorino and would be the last ones on.

"Additionally," Shimon went on, "Heavy Weapons Troop Training Detachment and Sapper TTD deploy operational."

"Tel Aviv Ten." Peled, again, "That means that Nablus and Deir Yasin will monitor the RHQ company freak. What was that? Hang on. Louder, Meir; I can't hear you."

There was a pause.

"It's a fair question," Shimon Bar-El said. "Repeat it."

Ari looked to Benyamin. "Which Meir?"

Benyamin shrugged. "Probably Meir Ben David, Nablus Twenty himself."

"Tel Aviv Ten. Yes, sir. Nablus Twenty wants to know what good it's going to do to put a sapper platoon--"

"Accurately, please," Bar-El said, gently correcting.

"--what fucking good it's going to do to put a fucking sapper platoon and a fucking heavy mortars platoon fucking operational until they've fucking gotten their fucking groceries and fucking tubes. I think I missed a 'fucking' in there."

"From what I hear, that'd be the first time, Mordecai. And it's a fair question," Shimon Bar-El said. "Two answers. First, you're operational because I want you off the buses first when we get there--your equipment should be already at Camp Ramorino, and I want your I&I before we turn in for the night. Secondly, you're operational because the way it works is that I'm the general and I get to decide how we do things."

A laugh echoed in the crowded bay.

"But relax, people. This is the easy part."

The last moments took forever. Automatically, Ari had tapped his right thumbnail against his left when Peled announced the time to touchdown--it was no warrior's reflex, but it was a trained one. His primary noncombatant assignment was as assistant to the RHQ company clerk, and one thing they taught clerks early and well is that timing is everything.

So he knew it was three minutes, but it was a long three minutes until the pilot pulled the nose up and set the craft down gently, like it was a passenger skipshuttle or something. Ari decided that a hard landing would have been as tough on the pilot as on the cargo.

The skipshuttle's wheels screamed. "We're down," Galil said.

"Like we can't hear," Benyamin said. He really didn't like Galil.

"Phones on," Shimon said.

Ari took his helmet off, set it down on his lap, on top of his rifle, and pulled his phone out from his chestpack, slipping the cup over his right ear, tightening the headband with one quick pull, spinning the sound louvers fully open with his right hand as he brought the mike down in front of his lips with his left hand. He gave five quick puffs into the mike to bring it into test mode; it gave a friendly quintuple chirp in his right ear. He slipped his helmet back on, snapped the faceplate down to make sure that it locked into place, then unlocked it and pushed it back up and into the crown of the helmet.

"Bar-El on All Hands One," Shimon said. "Test mode, all hands." He wasn't the only Bar-El in the Thirtieth Regiment--most of the Thirtieth was of the clan, and maybe five percent was of the family--but his idea of comm discipline, for himself, didn't require him to identify himself properly. It's called a double standard; Shimon Bar-El was a lot like that.

Ari puffed; his phone chirped.

They all started repeating "Testing, testing," a babel of voices in his ears.

"Tel Aviv Ten to all hands." Peled's call sign cut through the sound. "Sound off."

Ari quickly puffed for the fireteam freak.

"Everybody on?" Benyamin asked.

"Kelev One One Two Five," Ari said, blushing when Orde Lavinsky, the team medic, came on with an informal, "Orde here."

"Natan," Lavon said.

"Laskov," David Laskov said.

"Okay; everybody on to Platoon."

Ari puffed for the platoon freak. The first fireteam, Lipschitz's, was sounding off. Ari waited until he heard "Kelev One One One One; team freak nominal."

"Kelev One One Two Five," Ari said. Number five in the second team of the first platoon of the RHQ company, call sign Kelev. The others were supposed to use that, even in private conversation on the team freak.

"Kelev One One Two Four," Orde said, and the call was passed down the line.

Ari took his time puffing back to the company freak in time to hear the TTD commanders sound off.

"Deir Yasin Twenty; we're nominal," said Asher Greenberg, the commander of the heavy mortar training detachment.

"Nablus Twenty," Meir Ben David grunted, for the sappers. "I've got two fucking sets out. I'll have the fucking spares up in five minutes. Otherwise it's fucking nominal."

"I don't understand him." Benyamin bent his head close to Ari's, their helmets almost touching. "The man can set charges to cut a tree--any tree, any world--off at the base, flip it up into the air and set it down across a road, neat as you please, but he can't keep on the air to save his life."

"Kelev One Twenty and Kelev Twenty," Galil said, reporting both as First Platoon's leader, Kelev One Twenty, and as Kelev Twenty, the company commander. For administrative purposes while traveling, the two training detachments were considered part of the security element and configured as grossly oversized platoons under RHQ company. It wouldn't be the way Shimon Bar-El would take them into combat, but it was a handy means of organizing them while they loaded people on and off buses. "Nablus has two sets down," Galil said, reporting. "Otherwise, communications nominal. ET five minutes to nominal."

"Kelev Eleven Thirty-One," a dry voice said. "Hey, Kelev Twenty, that was real interesting and all, but maybe you should try that on a channel where the general is likely to hear it? You just reported that the company's okay on the Company freak. We kind of already knew that, sort of."

"Shit. And blush," Galil said. "I screwed up; I had both freaks open. Sorry, people."

"No problem, Yitzhak."

"That's easy for you to say, David," Galil said. There was a click.

By the time they were done testing, the skipshuttle had rolled to a stop. Distant machinery kachunked against the skin. With a whirr and a hiss and a clank, the forward hatch eased open.

Ari's ears popped. Forward and above his head, sunlight splashed into the dark of the crowded cabin.

"Tel Aviv Ten to all hands," Peled said. "Let's move it, people. By the numbers, we will unload, and smartly. You will use full grips and lanyards; pass the wrenches to the sides."

Unloading a full troop skipshuttle was supposed to take a solid hour--the men were packed in tightly, and after the top tier unloaded themselves it generally took the port loaders too long to unbolt and remove the top tier.

Administrative or operational, Shimon never liked having his people locked in, waiting on the pleasure or in the sights of others. Wrenches, tied to short lanyards, were ritualistically passed down to those of them up against the hull. Benyamin smacked one into the palm of Ari's hand.

Eager to get out, Ari let discipline slip for a moment; he started to rise, but Benyamin shook his head. "No. Tie it down."

He clipped the lanyard to a free ring on the front of his shirt, and waited while the upper tiers cleared themselves out.

"Eighth row, second tier, prepare to unbolt."

The soldiers two rows in front of them started moving. Ari released himself from his seat, passed his rifle over to Benyamin--dropping the wrench in the process; it was just as well it was tied to him or it might have dropped through the mesh and hit somebody on the bottom tier--and tightened the strap of his buttpack as he rose.

He unbolted the rack. Eager hands above grabbed it and stacked it; he traded the wrench for his rifle.

"Eighth row, go." They scrambled up to the narrow walkway and filed out of the dark.

And then the light hit him.

It hit him hard, like a physical shock. Which was understandable, he decided. He grew up in Metzada's underground corridors, under the glows of home. But Metzada is a dull world, of grays and browns, and the glows are a harsh, actinic light.

The regiment had just come off training exercises on DelAqua's Continent on Rand, but the northern part of DelAqua is a horrible joke on the watery name: it's a desert, and not the gentle rolling sand dunes in the southern part of Eretz Israel, but dry, cracked ground, broken only by squat, jagged mountains. All dark reds and browns and grays, sometimes eerily pretty at dawn or sunset, but mainly ugly under the dirty brown sky.

He had seen the holos in school, of course, but when you're really there, it's different. He knew that an analytical illumeter would say that the hue of the holos isn't an angstrom off that of reality, that the saturation is accurate to a thousandth of a percent, that the luminance doesn't vary by a decilambert, but he didn't care what an instrument said: it looks different when you're there.

Portocielo Grossi was a gray island rising out of a sea of color. Off to the north, the rolling hills were covered with an intricate blanket of luxurious blue-green, interwoven with red and yellow threads and slashed by weaving roads. To the west, a field of golden grain rippled gently, lovingly, in the wind. To the south, a shining lake of an impossibly deep blue beckoned invitingly.

The west wind brought smells of something delicate and floral, mixed with the warm brown smells of grasses baking in the sun, and a hint of a distant, acrid odor that would have been overpowering if it were any stronger.

It was all so beautiful he almost could have cried.

Benyamin touched his arm. "Down the stairs," he said, gruffly. "Something, isn't it?" he added, his voice soft.

"Move it, people, move it," Peled shouted, not bothering to use a mike when his bullhorn voice could serve. "We have ground transportation due here in just one minute. We will not keep them waiting."

They assembled on the concrete below; at a gesture from Galil, RHQ company shuffled off to one side.

"What I want to know," Lavon said, "is how we all can be locked up in the same shuttle for the same time, in the same size seats, and I come out looking and feeling like I've been hung in a meat locker and Galil looks like he just stepped out of a training holo."

Lavinsky chuckled. "You got a point. Complete to the rifle stuck up his ass."

Ari looked over at the captain. Yitzhak Galil stood too stiffly on the tarmac, his face and khakis unwrinkled. His short hair was slicked down and neatly parted, his beard and mustache closely trimmed. The only note out of harmony were his sleeves, rolled up to reveal arms thickly covered with black hair. Even so, the sleeves were rolled up neatly.

"What do you bet he combs his forearms?" Benyamin asked.

"All Kelev units," Galil called out, "check your weapons." He was unslinging his own assault rifle as he spoke.

Benyamin gathered his squad around him. "Lock and load," he said, unfolding his Barak's metal stock.

It was mechanical, something Ari had done a hundred thousand times: flick the selector all the way forward to full automatic with the right thumb, then pull it back through five-shot, three-shot, single-shot to safe; check to see that the rear sight was obscured by the brown shutter that indicated the weapon was on safe; then brace the butt of the weapon against his belly, under his chestpack, while he reached up and took a magazine from his pack--the ammo on his web belt was to be used last, not first; the chestpack could be disposed of when empty--and slammed it into the receiver with a satisfying, rippling click.

His hand fell to the charging bolt, but he caught himself and let the rifle hang from its patrol sling.

"Hey, Orde?" Benyamin raised an eyebrow. "You special?"

Lavinsky, the medic, hadn't unfolded the stock or used his patrol sling; he had loaded his rifle, then hung it on the right side of his H-belt, balancing the load of his medical kit on the left. "It's easier this way," he said.

"Tell you what," Benyamin said. "I'll get you a nice medic's brassard--Christian cross and all--and we can make you a real good target."

Lavinsky laughed as he tugged at his scraggly black beard. "Okay, adoni, okay." He took his Barak from his belt, unfolded the stock and rigged the rifle patrol style, the strap running over one shoulder, across the back of his neck, leaving the rifle hanging in front, just above his waist. "Not to worry, eh?" He bounced experimentally on the balls of his feet. "Feels good to be back, eh?"

Benyamin shrugged. "My first time here. I was in the 101st RCT when the Fifth was on Nueva. The 101st was broken up five years ago, not six."

"Not in '26?"

"Honest. It was in '27. I was there. Trust me."

It was Lavinsky's turn to shrug. "Shit. All blurs together after a while. 'See strange new worlds, experience exciting cultures and meet strange and interesting creatures--'"

"--and kill them,'" Benyamin finished. "That joke was old when I was young."

"Hey, to an old man like me, you're still young." The medic was the oldest member of the squad, well into his forties. Probably getting ready for retirement, Ari decided. For a private soldier--even one with a medic's warrant--it would be either retirement at forty-five or back to school to get a medician's caduceus, or both. Medicians could make a decent living on Metzada, although not as good as combat pay or even cadre pay allowed. But Orde Lavinsky only had one wife, and both of their children were grown; he might not mind moving to a smaller flat.

Ari took a moment to look around the landing field. Civilian, not military: Thousand Worlds Commerce Department type. Facilities above ground, tall buildings of concrete, glass and steel poking hundreds of meters into the sky, protected by evenly spaced skywatches at the perimeter. Laser launcher near the south wall, the twin mushrooms of its power plant sending white puffs of steam into the afternoon air.

A gleaming tractor, looking more like an oversized child's toy than anything else, clanked toward the skipshuttle, dragging a long, thick power cable across the hot tarmac.

"HQ, spread out," Peled said, gesturing them all away. "We're operational, remember?"

"Nah," Shimon Bar-El said. "Bunch up and save them the trouble."

They spread out.

Shimon Bar-El wasn't much to look at, as he stood on the hot tarmac, considering the horizon between puffs on his tabstick. He was a decidedly average-looking man in his late forties, a bit less stocky and broad-shouldered than was usual for somebody raised under Metzada's one point two standard gees, his close-cropped hair more a faded blond than gray, his nicotine-stained stubby fingers always wrapped around a stylo or near the keys of a typer, when they weren't playing with a lit tabstick.

He smiled very rarely and very little.

His rumpled khakis were usually caked white with salt under the sweat-stained armpits, although he wore no field pack, carried no heavy gear at all--just a durlyn briefcase, which he handed to Avram Stein as he turned to confer with Galil.

A holster hung from the web belt pulled tightly around his gut, but it always carried tabsticks, not a pistol. He was famous for being a terrible shot--he was even worse than Ari, and that was pretty bad. Bar-El didn't carry any sidearm except a knife--a line infantryman's utility knife, not a skirmisher's Fairbairn dagger.

Shimon Bar-El dipped two fingers into his holster and pulled out a tabstick, puffing it to life as his eyes took in the field.

His eyes were special. Not just because he had the epicanthic folds that some Metzadans had inherited from the few Nipponese who had been exiled along with the children of Israel. That wasn't uncommon.

The eyes were special because they could see anything.

That's what they all said. Shimon Bar-El's eyes came to rest on Ari's for a moment. Ari was sure that the general could see that he was a coward, that he was going to disgrace his family, his clan, his world, his people.

But then the eyes turned away to two men standing next to him, Avram Stein and Dov Ginsberg, and Shimon's expression softened faintly.

Dov was a head taller than Shimon and almost twice as broad across the shoulders. Dov's hairline came to within a centimeter of his heavy brows as he stood squinting in the bright sunlight. He was an ugly man, but not pleasantly so, like Benyamin; the proportions were all wrong. His arms were too long, as was his torso. His legs would have looked normal on a shorter man, but they looked almost comical on him, although nobody laughed at Dov.

Avram was skinny, too skinny for a Metzadan. And he wasn't Metzadan, not by birth. Neither was Dov; they were both survivors of the Bienfaisant affair, of Shimon's Children's Crusade, halfway around this planet and a quarter of a century ago.

Ari had heard about it, but he wasn't sure he would have believed that it was possible even for Shimon Bar-El to have carved his way through enemy lines with nothing more than a couple hundred child-soldiers... except that there were six survivors--seven, if you included Shimon--who had lived to tell the tale. Not that they talked about it much.

Peled's rifle barrel must have come a degree too close to pointing at Shimon; Dov batted it away with the butt of his shotgun. Peled started to complain, then grimaced and shrugged apologetically.

"Dov, be still," Avram said.

Dov ignored him. He wasn't open to reason about people pointing guns at Shimon.

Dov lightly, reverently, like a rabbi lifting the silver pointer to read a spread Torah scroll, tapped Shimon on the shoulder, then pointed when Shimon looked up.

"Thanks, Dov. Transportation's almost here," Shimon said, raising his voice. "I was wondering if we were going to have to stand in the hot sun until the other groups were down." That would be several hours away, at least; there were two other full shuttles still skyside, in the TW troop transport, and they needed the same window that the first skipshuttle had used to bring down HQ, the Support/Transport/Medical Company, and the Sapper and Heavy Weapons troop training detachments.

Four buses hissed over the tarmac, the blast from their plenum chambers sending sand and grit whipping into the air, then one by one settled down onto their rubberized skirts. They were wide, squat vehicles, windowed all the way along their length, windows covered with a drab green mesh.

A slim man--a Casa light colonel if Ari was correctly reading the broken golden stripes on the collar of his tailored fatigues--got out of the nearest bus and was guided over to Shimon. At Shimon's nod, Avram pointed a microphone at him. When in doubt, fill the troopies in.

Ari puffed for All Hands Two, the selectable all hands channel.

"Tenente Colonello Sergio Chiabrera, senior aide-de-camp to Generale DiCorpo d'Armata Massimo Colletta," the Casa said, drawing himself to attention, and saluting crisply.

Lavon snorted. "He does that real nice."

"Shut up," Benyamin said, without heat.

"Generale Shimon Bar-El? Very good, Excellency. My orders," Chiabrera said, producing a sheaf of flimsies. "We can have your men at camp in about an hour. Generale DiCorpo d'Armata Colletta sends word that he would like the pleasure of your company at table tonight--as soon as your men are settled in, of course. We dine at the twentieth hour, local time."

"I'll be there," Bar-El said. Some of the Metzadans had started to drift over toward the bus. "Mordecai," he said.

"Tel Aviv Ten. As you were, people," Peled snapped out. "Let's pretend we're all soldiers, shall we?"

Shimon jerked his chin toward Galil. "Check it out."

Galil picked out Benyamin and two other fireteam leaders by eye. Ari followed his brother up the ramp and into the darkness of the second bus. It wasn't anything special, he decided; just a converted civvy vehicle, turned into military transportation by the addition of mesh grenade screens to the windows.

Benyamin rapped a ring against the nearest window. "Glass. Shit."

"Kelev One One Two Two," Laskov said. He was all the way in the back. "Somebody's idea of cleaning out this thing was to shove a bunch of old bottles and tools under the back benches."

"We'll clean it out, then move out," Shimon Bar-El's distant voice said.

"My apologies, of course, Generale, but I'm afraid I don't understand the problem."

"No big deal, Colonel," Peled said. "But you have to keep gear stowed away. If the bus hits a mine, the bang turns every loose bottle or piece of metal into shrapnel. Pretty mean shrapnel," he said, idly rubbing the edge of his thumb against an old scar on the bridge of his nose. "Never knew no nice shrapnel, and that's a fact."

"But we are 200 kilometers from the front, and the front is quiet."

"His fucking point pre-fucking-cisely." For a moment, Ari thought that it was one of the soldiers near the colonel who had said that, then he realized it was Meir Ben David, the sapper captain, on All Hands One.

"Shut up, Meir," Shimon Bar-El said quietly. He turned to Peled. "Mordecai, send a detail to police the buses."

"Tel Aviv Ten. Yes, Shimon."

"We have to--" A helo roared by loudly overhead, sending some hands to the grips of their weapons, everybody desisting when Shimon came back on All Hands One. "Easy, people, easy. Few of us are operational, and none of us are engaged."

"Not at the moment we aren't," Benyamin said as they walked out into the daylight. "Not fucking yet."

Copyright © 1990 by Joel Rosenberg

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details