Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

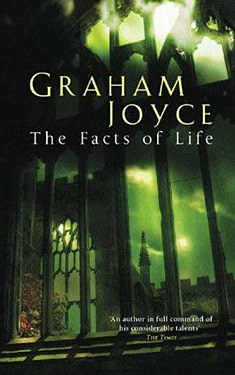

The Facts of Life

| Author: | Graham Joyce |

| Publisher: |

Gollancz, 2003 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Historical Fantasy |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Winner of the 2003 World Fantasy Award Graham Joyce chronicles a haunting, war-torn terrain in this heartrending novel of one family's quest to begin again -- without forgetting the lives they left behind.

The Facts of Life

Set in Coventry, England, during and immediately after World War II, The Facts of Life revolves around the early years of Frank Arthur Vine, the illegitimate son of young, free-spirited Cassie and an American GI. Because Cassie is too unreliable and unstable to act as his proper guardian -- and is prone to "blue" periods in which she wanders off without warning or recollection -- Frank is brought up in the care of his strong-willed, stout-drinking grandmother, Martha Vine, who has, among other homemaking talents, the untoward ability to communicate with the dead.

So begins the first decade of Frank's life, one in which ghosts have a place at the table and divine order dictates the outcome of his days. Along the way there are brief stays with each of his six eccentric aunts, visits to the local mortuary, and voices inside of his own head that suggest that he, too, has the gift of supernatural intuition. An affecting tale of family and history, war and peace, love and madness, The Facts of Life will leave readers spellbound with its resounding expression of magic realism.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

If she's not here, thinks Cassie, if she's not coming. If she's not here, then what? Then what?

Cassie Vine, just turned twenty-one but dry-eyed, holds the unnamed baby inside her coat and squints into the wind. It is twelve noon, three weeks after Victory in Europe day, and she stands on the white stone steps under the portico of the National Provincial Bank waiting to make the handover. Before her groans the blitzed and broken city of Coventry. Opposite, the hollowed shell of the Owen & Owen department store; to the right the burned-out medieval cathedral, its shattered gothic arches and spire like the ribs and neck of a colossal excavated creature; in between, the flattened, scooped-out wastelands and the fractured department stores awaiting demolition. Cassie hugs her baby.

She's done this before. Four years ago, on these same steps, under the same neoclassical roof, but before the rubble and the twisted metal tramlines were cleared, while broken water pipes still gurgled and fizzed under the toppled bricks. Before this line of inadequate, temporary shops was erected along Broadgate. That time a girl. This time a boy. And if she doesn't come, thinks Cassie, then what?

I'll damn and bloody well keep it, that's what. They can say what they like. They can bloody damned well bugger off. She opens her coat and parts the blanket from the sleeping baby's face, and her heart squeezes. Because she knows it should be different. Because after the last time her girlish heart felt like a bombed-out cathedral, smoking ash, twisted altar, smashed stained glass, father forgive. Five past twelve and still no sign. I'll give her until a quarter past thinks Cassie. That's all. Until a quarter past.

She can't be trusted, you see, Cassie can't be trusted. What kind of a mother would Cassie make? So her sisters said, so they whispered in beseeching, kindly voices, but with a hardness of heart underneath all their good intentions; no Cassie, it's not right. You know you can't manage. What are you going to do when you have one of your episodes, Cassie, what will you do? Think of the mite. Poor little thing, think about him. Give him a straight chance, Cassie, where there's a need and there's one calling for him.

Beatie it was, her sister, punching rivets into the fuselage of Lancaster bombers, who'd found one willing. Just like the last time. Seems with the shortage of men these days there is always one woman willing. She'll be there at twelve o'clock sharp, Cassie, mind you're not late. You don't want to be seen hanging around, and neither does she. And last time that's how it was, the clean handover at twelve noon, with no words said, not a syllable and not a breath. No questions, no name, no pack-drill, the handover made and the girl gone. But this time, late.

Ten past twelve and still not come. Cassie rocks her weight from foot to foot, staring every approaching woman in the eye, freezing them in the crosshair of her gaze, but none come to claim the bundle of boy. The child she hasn't yet named. No, don't name him, Cassie, that will only make it harder when the time comes. A name will make him real to you. As if this parcel of gurgles and wails and vomit and infinite fleshy sweetness were not already real, as if it were not part of her, as if her liver or gut were not part of her, as if she could give it up without the sound of skin ripping and the sensation of bone cracking.

This is a place where prostitutes stand of an evening, sister Una had told her, raising a single eyebrow. On the bank steps. Ladies of the night. Trollops. Cheap perfume and American nylons. Why give it away when you can get good money? Cassie wonders if those women stood in the exact spot she now stands. Spraying their scents, like alley cats.

She looks up. The blasted cathedral spire of St. Michael's pricks the blue clouds, and her heart skips, count of one. At the second spire of the Holy Trinity and it skips again, two. And she thinks of the slender tower of St. John's behind her, three. And keeps counting in this city of the three spires: one, two, three. Because on three you jump. And at any moment she feels she might.

Twelve-twelve and Cassie feels a thrill, a flush of possibility in the idea that the woman is not coming. Then, through the crowd she sees an upright figure in a navy-blue coat and black scarf making a direct line toward her, a pinched face and a jaw like cathedral rubble, mouth pursed, brittle eyes. At that moment -- but only for Cassie, who sees what others refuse to see -- a lance of golden light hurtles from each of the three city spires, intersecting at a point of fire in the bundle in her arms. No, thinks Cassie, it's not going to happen this time, and she counts one, two, three and she leaps through the triangle of light into blue space, taking the baby with her and leaving the woman in the navy-blue coat standing on the steps of the bank, arms outstretched, open-mouthed, appalled.

CASSIE IS WAYWARD, Cassie is fey, Cassie is the last girl on earth fit to raise a child. Everyone is agreed. But when Cassie returns to the family home adjacent to the closed sewing-machine shop they see her with the infant bundle and they stop talking.

For they are all there, the sisters. Gathered for support. This is what the Vines do at times of crisis, moments of import. They regroup, circle the wagons, take up position. All six of her sisters, plus mother Martha large in her chair under the loud ticking mahogany wall clock, by the coal fire, smoking her pipe. Martha's yellow teeth clack on the pipe stem in the explosive quiet. It is Martha's hooded eyes Cassie meets first. Then everyone talks at once.

"Her's brought him back, her has," Aida declares, as if what is required at that moment is a brilliant statement of the obvious. "Well, our Cassie!" says Olive. Damp-eyed Beatie asks, "She's not turned up then?" "Don't tell me," goes Ina. "What's a-goin' on?" Una wants to know. "Here's a fine pass," says Evelyn.

And Cassie sighs. She stands and sighs, a lovely rose flush brought to her cheeks by the warmth of the fire in the grate. It's as if she isn't there amid these noisy, questioning, caring sisters; Cassie with her soft, lustrous, gypsy-black curls and candid blue eyes, dreaming, hugging her unraveling bundle while everyone shouts, argues, gesticulates, and wrings their hands.

It is Martha who brings her back and all of the other sisters to order by rapping her walking stick on the side of the coal scuttle. "Hush up! Hush up! Let's have us a bit of peace in the house. Cassie, take off your coat. Olive, give the girl a cup of tea, will you? And Cassie you give me the babby while you sort yourself out. And everyone else just hush up!"

Martha accepts the baby from Cassie and sits back in her chair. Olive pours tea. Una helps Cassie off with her coat, and stands, feet together, with the coat folded over her arm, as if Cassie might at any moment be instructed to put it back on again. Beatie pulls a chair from under the gate-legged table. Cassie sits gratefully. She sips her tea, composing herself while the others wait.

Martha Vine can command any room, always appearing taller and more stout than her slender frame ought to allow. And if she needs further authority it is conferred by a coronet of hair the hue of pewter fenced behind a row of steel hairpins.

"Now, then," Martha says, knocking out her pipe into a bowl on the arm of the chair. "Tell us what's passed."

"Nobody came. That's it. That's all."

"I'm surprised at that," Beatie says. "I'm more than surprised."

"Where have you been all this time?" Martha wants to know. It was gone four in the afternoon. "Not waiting, surely?"

"Wandering."

The sisters exchange looks at this. Looks of confirmation. This, after all, is why Cassie can't be trusted to rear a child. She is given to wandering. Martha turns to quiz Beatie on her contact at the Armstrong-Whitworth bomber factory. "Are you sure it was all aboveboard?"

"Of course, I'm sure. It was Joan Philpot's sister. She can't have children on account she -- "

"On account she hasn't got a husband!" Una puts in.

"She did have one in the navy but he went down with the Hood. But it isn't that. I mean, she could always find another sailor, couldn't she? No, she had her womb took away when she was only twenty. And Joan said she was distracted for it. Painted the room up herself she had. Though she really wanted a girl, she was still mad to have him she was."

"You didn't give her the wrong time?"

"Midday, today, steps of the bank! I'm not bloody stupid. I can't believe she didn't come. How long did you wait, Cassie?"

"I waited plenty."

"How long?"

"I gave her until quarter past the hour."

"Quarter past!" Beatie cries. "She might have been delayed! You could have at least waited the half hour!"

"At the very least!" Olive says.

That gets them all shouting again, discussing how long it is reasonable for a woman to wait before passing on her baby to a stranger. Aida protests that for a thing like that she would see out the hour. Beatie too. Ina says Cassie must have turned around the moment she'd got there. Only Una and Evelyn seem to think a quarter of an hour long enough to wait.

Martha bangs her stick on the coal scuttle again. "We'll have to set up another handover. That's all there is for it."

"No," Cassie says.

"Well, you can't keep it, girl, we've been through all that."

"No."

The sisters remind Cassie of why she can't keep it. There was that time when she had gone missing for a week and no one knew where or why to this day. There was the time the policeman brought her back at three o'clock in the morning when she'd been found wandering the blitzed shell of Owen & Owen. There had been the episode with the American GIs, and look where that had got her. And the time the fire brigade had had to get her down off the roof. And the time she'd drunk that whisky Olive's husband had looted from Watson's cellars. Not to mention the fearful night of the Coventry blitz itself. Not to mention that. And on and on.

What sort of a mother are you going to make, Cassie?

Cassie cries. She puts her head on the table and cries.

"I'll see if I can't set up another handover," Beatie says softly.

Martha holds the baby boy, just seven days old, and regards her own youngest daughter steadily. Tears have no record of working their way with Martha. But to everyone's surprise she says, "No. Maybe the moment has passed."

"What do you mean?" says Evelyn.

"I mean," Martha says, "that sometimes when people are late they are late for a reason. Sometimes things have a way of telling you they're not right."

"But her can't keep him," Aida says. Aida is the eldest daughter, already in her mid-thirties and thereby entitled to front opposition to Martha's will. "It wouldn't be fair to the boy. And you know none of us are in a position to have him. And you're too old, what with your stick and one thing and another."

"I know none of you wants him," Martha agrees. "We've been through all that. And I don't see why any of you should have the burden of the child. She's had the pleasure, and she has to have some of the gall. But listen to this. There's every single one of you feels rotten about how we give the other away. Every single one of you. And I do, too. There isn't a day goes by when it hasn't played on my mind. So maybe we can put it half right."

"How we going to do that?" says Aida. "And here's me with my asthma."

"We'll share him," says Martha. "Turn and turn about."

"Share him?" Olive shrieks. "We can't share him!"

"We can and we will," Martha avows. And she hugs the boy and chucks his chin.

The sisters all start arguing at once. The room is an aviary of voices raised in competition. Cassie looks up as into this pandemonium walks Arthur Vine, Martha's husband, father to all the girls. Cassie was always his favorite, but he can't find a smile for her this time. He nods briefly at her and ignores the others. It is a moment of sanction. Cassie lifts her head and mouths a silent thank you to the old man. But he can't stand the commotion. He waves an arm through the air and leaves the room. It is, after all, a woman's thing.

Martha clacks her stick against the coal scuttle, silencing everyone for a third time. "Hark!" she says. "Hark! Was that someone at the door?"

Martha often "hears" someone at the door. The sisters are accustomed to it. They pretend to listen hard for a moment. "No one there, Mam," says says Beatie. "It's nobody, Mam," Una says. "Nobody."

Martha slumps back in her chair under the ticking clock. For with the arrival of nobody at the door, it seems a decision has been reached.

Copyright © 2003 by Graham Joyce

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details