Added By: Engelbrecht

Last Updated: illegible_scribble

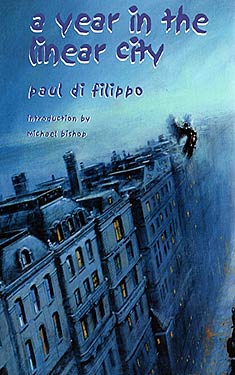

A Year in the Linear City

| Author: | Paul Di Filippo |

| Publisher: |

PS Publishing, 2002 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novella |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Hugo-nominated Novella

A moderately modern city, pulsing with music and commerce, seemingly of infinite length, yet only as broad as a wide avenue, flanked on one side by Heaven, on the other by Hell. Such is the milieu intimately familiar to -- and mostly unquestioned by -- the millions of average humans who inhabit the Linear City. Yet a small band of seekers do indeed ponder their odd lot, the genesis and fate of their strange habitation. Among the speculatively minded are a small group of writers who specialize in what they call "Cosmogonic Fiction." And among these men and women we find Diego Patchen, one of the younger luminaries of his set. A Year in the Linear City is the story of Diego and his friends, their loves and rivalries, their failures and triumphs, during one pivotal year beneath the Seasonsun and Daysun, in forbidding sight of The Other Shore and The Wrong Side of the Tracks. Careers will flourish, comrades will part forever, subterranean adventures will endanger both soul and city, and a fateful expedition to faroff Blocks will bring new and challenging perspectives, leaving no one unchanged.

Excerpt

A Dread of Yardbulls

February, and his father could talk only of his own impending death, swearing wildly that he saw coveys of Yardbulls massing specifically for him, ragged-winged specks afloat like flakes of ash in the warped fulgurant smokes of the northern rim of the world. Cold soul in a chilly Trackside/Trackview flat, the old man raved freely at those odd intervals when Diego Patchen forced a reluctantly filial visit upon him, as if caching all his hourly fears and recriminations until the arrival of his lone child. Much to the son's astonishment, but true to the old man's character, Diego thought to detect in his father's fearful vituperations a note of savage pride, as if the postulated quantity of Yardbulls necessary to drag the antique sinner to his posthumous fate merited some perverse applause.

The Seasonsun gone entirely from the sky that month, slush heaped the gutters of Broadway, as if all the flavored-ice carts of August had spilled their contents, both Trackside and Riverside. (Did the distant, generally imperceptible heat from the Wrong Side of the Tracks possibly melt the slush slightly at the corresponding curbing, while the cooling mists of the Other Shore gelled more firmly the parallel glaciated sluice? Perhaps, but perhaps not. True, in summer residents of Trackside buildings claimed to swelter more than their cross-Broadway neighbors, while heralding a compensatory lowering of the thermostat in winter. And equally true, Riverside dwellers shivered a wee bit more in winter, but boasted of their residential coolth when rat days raged beneath the ascendant Seasonsun. But Diego, favoring the rationalism of an ingeniator, was inclined to believe that neither effect from the antipodal regions was real, but only psychosomatic reactions to the respective proximity of Tracks and River.) Going out to visit the old man was an offputting chore in the best of weathers, but particularly tiresome at this time of the year.

Diego lived in the Borough of Gritsavage. Population: 100,000 or so, distributed up and down one hundred Blocks; current Mayor: the loudly opinionated Jobo Copperknob; ambiance: despite the Borough's grim appellation, quite cultured and congenial. Diego's digs: a Streetview apartment on the 10,394,850th Block of Broadway, above a fruit and vegetable store named Gimlett's Produce. (His father dwelled just a few Blocks Downtown.) The bluestone building housing Diego and his immediate neighbors occupied the Riverside of Broadway.

Streetview and Riverside both: sweet. (Not always thus. Diego frequently winced to remember a childhood of grim days and eerie nights spent in the same apartment that now housed the dying Gaddis Patchen. The subliminally whispering distant flames from the Wrong Side of the Tracks cast capering shadows on young Diego's bedroom walls no matter how firmly he tried to paste the lowered green oilcloth rollershade against the window glass before sleep. And the regular roar of Uptown-bound trains rattled those same panes. What Diego enjoyed nowadays, he had earned through his own endeavors, not effortless inheritance.)

This overcast winter morning, Diego, lazing a-bed, found real wakefulness hard to attain. A late night out with friends-involving too many cigarettes, an excess of highflown bloviation and a constant stream of hops-heavy Rude Bravo beer from the neighboring Borough of Shankbush-had taken its predictable toll. Mired in his clammy sheets, Diego's sour mood allowed him to contemplate only the many injustices thrust upon him by existence, rather than any of the compensating glories. Thus the parade of his thoughts featured such performers as these:

His cheap and refractory landlord, Rexall Glyptis, who had for months running now failed to hire even an apprentice ingeniator to repair the radiators in Diego's apartment, a failure made all the more galling by the fact that the heatful steam itself was free, piped beneath every Block as part of the ineffable infrastructure of the Linear City.

His best friend, the impulsive and wily Zohar Kush, who had discovered the saloon in the10,395,001st Block of Broadway named The Lookalike Boys, where Rude Bravo flowed like liquid suicide, and who had insisted on staging a drinking contest with some of the Shankbush locals.

Kush's newest lover, the capricious Milagra Eventyr, who had, by sensually occupying Diego's lap at one point in the boozy, bleary evening, precipitated a fight with Diego's own lover, the formidable Volusia Bittern.

Volusia, in turn, came in for her share of mild mental recriminations, as Diego recalled how she had punctuated her jealous accusations with a wild swing at Milagra-a swing which fortunately, given Volusia's physical proportions vis a vis Milagra, had failed to connect, due to a certain boozy skewing of perceptions. The hot temper some devilishly attractive women had!

And then of course one could not omit from the catalog of infamy Yale Drumgoole, Diego's fellow writer. Although neither a proponent nor practitioner of CF and consequently a member of a rival literary camp, Yale had been invited along for the night's spree. But Drumgoole's one accomplishment of the evening had been only to prove his utter inability to process internally more than five pints of Rude Bravo without blithely and crudely propositioning the wife of the brutish bouncer of The Lookalike Boys, thus earning the Patchen party summary ejection into the Shankbush slush, which differed not one whit in its wet chilly properties from the slush one-hundred-and-fifty-one Blocks Downtown.

Memories of the sight of the puffy flesh around Yale's left eye mottling colorfully as they all rode the Subway home cheered Diego up slightly, and he inched several toes out from under the blankets to test the air. Much too frigid. Perhaps there was some veracity after all to the notion that Riverside buildings were prone to effects from the Other Shore....

Music might help. Diego dashed a lean bare arm out to snap on the radio on his bedstand. Once its tubes warmed, brilliant trumpet notes, unmistakably phrased, swelled like a chorus of Fisherwives, and Diego's heart immediately lifted.

Rumbold Prague was a genius, maybe the only genius Diego personally knew. The black musician, his phtisic visage perpetually cool behind his onyx-lensed cheaters, dapper in his trademark gabardine trousers and loose silk shirts, typified for Diego all that art could achieve. Diego's own prose was most accomplished, he knew, wherever he let it be inspired by and emulate the unpredictable fluencies of Prague's lyrical compositions.

The cut ended, and the announcer came on. "That was 'The Road Goes Ever On.' Rumbold Prague, trumpet. Lydia Kinch, sax. Scripps Skagway, piano. Lucerne Canebrake, bass. Reddy Diggins, drums. From the Roughwood shellacker, Burning Fountains, catalog number RLP4039. Next up, Percival Ragland's 'Aeota.' But first, the ten o'clock news."

Diego groaned. Ten o'clock! If he were to cram both a visit to his father and some writing into the hours between this moment and his dinner date with Volusia Bittern, he had not a second to spare. But a dilemma presented itself: the order of his actions. Were he to begin writing immediately, he might labor on in a creative trance, unwitting of the time, and miss any chance to visit Gaddis Patchen. Go first to his father, and Diego would almost certainly emerge from his boyhood home full of strong emotions that would taint that day's writing.

After momentary hesitation, Diego let duty to his blood win out. He was a professional writer, after all. Surely he could put by any distractions to his craft. Did Rumbold Prague let his hypothetically ill-tempered father sour his embouchure? Not likely!

Diego hopped out of bed, clad only in his skivvies. After a hot shower (at least that utility had survived the incompetence of Rexall Glyptis) and the application of his favorite cologne, Meyerbeer's No. 7, to his near-beardless face (curse these boyish looks! thought Diego for the uncounted time), he felt halfway human again. Dressing in his favored winter outfit of tweed trousers, denim shirt, wool vest and baggy black jacket, he acknowledged that his stomach might have forgiven last night's excesses enough to accept a meal. But a quick check of the icebox revealed nothing fit for human consumption, and Diego resolved to pick up something enroute to his father's. He scuffled into his battered brogues and left his apartment with a wistful glance at his disordered writing desk.

Tripping lightly down the single flight of stairs to the street-familiar banister smooth under his touch, metal insets on the wooden risers offering firm purchase, old cooking odors historying the habits of his neighbors-Diego found himself alternately rehearsing the next section of his story in progress and trying to come up with some conversational tactic that might jar his father from his accustomed paranoid rut.

Once on the busy sidewalk, Diego immediately encountered Lyle Gimlett arranging some cold-tolerant produce-potatoes, turnips, apples and the like-in his outdoor stands to attract whatever trade he could from the bustling mass of pedestrians. The burly, slope-browed businessman-as always, a five o'clock shadow lending his face a smudgy look-hailed Diego in a friendly fashion.

"Patchen! In the market for some fresh bananas? The latest Trains have brought some particularly fine ones. Can't say when we'll see their likes again."

"Sure, Lyle. Save me a bunch of green ones, and I'll pick them up later today."

Diego rucked up his jacket collar against the chill and made to move off, but Gimlett stopped him with a hand on Diego's elbow. The grocer leaned in conspiratorially and said, "Any chance you and your pals will be getting more of these soon?"

From beneath the bib of his white stained apron, Gimlett produced an odd locket. Strung on a leather cord threaded through a drilled hole, a thick iridescent reptilian scale big as a fat potato chip shimmered in chromatic uncertainty across most of the spectrum.

Diego flinched from the sight. Bad memories of dire times, when he had been down on his luck and willing to take risks that nowadays appeared unacceptable, tumbled out of the mental attic trunks where he had thought them safely stored.

"I-you need to talk to Zohar Kush about more scales."

"Fine, fine, you both come around some evening after the store's closed. I'll give you a good price for them, since I can sell as many of these as you can get me. People always need a little good luck. Here, take an apple, Diego."

Diego accepted the fruit and hustled off. But once out of sight of Gimlett, he consigned the fruit to the gutter, despite his hunger, where it sat cradled in dirty winter icy suspension like an insouciant autumn orphan.

Copyright © 2002 by Paul Di Filippo

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details