Added By: valashain

Last Updated: Administrator

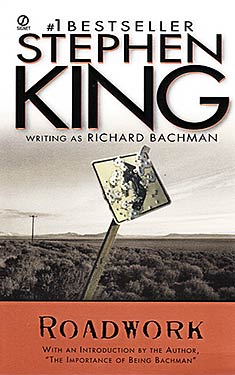

Roadwork

| Author: | Stephen King |

| Publisher: |

Signet, 1981 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Horror |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Psychological |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

What happens when one good-and-angry man fights back is murder--and then some....

Bart Dawes is standing in the way of progress. A new highway extension is being built right over the laundry plant where he works--and right over his home. The house he has lived in for twenty years... where he has made love with his wife...played with his son.... But before the city paves over that part of Dawes' life, he's got one more party to throw--and it'll be a blast....

Excerpt

November 20, 1973

He kept doing things without letting himself think about them. Safer that way. It was like having a circuit breaker in his head, and it thumped into place every time part of him tried to ask: But why are you doing this? Part of his mind would go dark. Hey Georgie, who turned out the lights? Whoops, I did. Something screwy in the wiring, I guess. Just a sec. Reset the switch. The lights go back on. But the thought is gone. Everything is fine. Let us continue, Freddy--where were we?

He was walking to the bus stop when he saw the sign that said:

AMMO HARVEY'S GUN SHOP AMMO

Remington Winchester Colt Smith & Wesson

HUNTERS WELCOME

It was snowing a little out of a gray sky. It was the first snow of the year and it landed on the pavement like white splotches of baking soda, then melted. He saw a little boy in a red knitted cap go by with his mouth open and his tongue out to catch a flake. It's just going to melt, Freddy, he thought at the kid, but the kid went on anyway, with his head cocked back at the sky.

He stopped in front of Harvey's Gun Shop, hesitating. There was a rack of late edition newspapers outside the door, and the headline said:

SHAKY CEASE-FIRE HOLDS

Below that, on the rack, was a smudged white sign that said:

PLEASE PAY FOR YOUR PAPER!

THIS IS AN HONOR RACK, DEALER MUST PAY

FOR ALL PAPERS

It was warm inside. The shop was long but not very wide. There was only a single aisle. Inside the door on the left was a glass case filled with boxes of ammunition. He recognized the .22 cartridges immediately, because he'd had a .22 single-shot rifle as a boy in Connecticut. He had wanted that rifle for three years and when he finally got it he couldn't think of anything to do with it. He shot at cans for a while, then shot a blue jay. The jay hadn't been a clean kill. It sat in the snow surrounded by a pink blood stain, its beak slowly opening and closing. After that he had put the rifle up on hooks and it had stayed there for three years until he sold it to a kid up the street for nine dollars and a carton of funny books.

The other ammunition was less familiar. Thirty-thirty, thirty-ought-six, and some that looked like scale-model howitzer shells. What animals do you kill with those? he wondered. Tigers? Dinosaurs? Still it fascinated him, sitting there inside the glass case like penny candy in a stationery store.

The clerk or proprietor was talking to a fat man in green pants and a green fatigue shirt. The shirt had flap pockets. They were talking about a pistol that was lying on top of another glass case, dismembered. The fat man thumbed back the slide and they both peered into the oiled chamber. The fat man said something and the clerk or proprietor laughed.

"Autos always jam? You got that from your father, Mac. Admit it."

"Harry, you're full of bullshit up to your eyebrows."

You're full of it, Fred, he thought. Right up to your eyebrows. You know it, Fred?

Fred said he knew it.

On the right was a glass case that ran the length of the shop. It was full of rifles on pegs. He was able to pick out the double-barreled shotguns, but everything else was a mystery to him. Yet some people--the two at the far counter, for example--had mastered this world as easily as he had mastered general accounting in college.

He walked further into the store and looked into a case filled with pistols. He saw some air guns, a few .22's, a .38 with a wood-grip handle, .45's, and a gun he recognized as a .44 Magnum, the gun Dirty Harry had carried in that movie. He had heard Ron Stone and Vinnie Mason talking about that movie at the laundry, and Vinnie had said: They'd never let a cop carry a gun like that in the city. You can blow a hole in a man a mile away with one of those.

The fat man, Mac, and the clerk or proprietor, Harry (as in Dirty Harry), had the gun back together.

"You give me a call when you get that Menschler in," Mac said.

"I will... but your prejudice against autos is irrational," Harry said. (He decided Harry must be the proprietor--a clerk would never call a customer irrational.) "Have you got to have the Cobra next week?"

"I'd like it," Mac said.

"I don't promise."

"You never do... but you're the best goddam gunsmith in the city, and you know it."

"Of course I do."

Mac patted the gun on top of the glass case and turned to go. Mac bumped into him--Watch it, Mac. Smile when you do that--and then went on to the door. The paper was tucked under Mac's arm, and he could read:

SHAKY CEA

Harry turned to him, still smiling and shaking his head. "Can I help you?"

"I hope so. But I warn you in advance, I know nothing about guns."

Harry shrugged. "There's a law you should? Is it for someone else? For Christmas?"

"Yes, that's just right," he said, seizing on it. "I've got this cousin--Nick, his name is. Nick Adams. He lives in Michigan and he's got yea guns. You know. Loves to hunt, but it's more than that. It's sort of a, well, a--"

"Hobby?" Harry asked, smiling.

"Yes, that's it." He had been about to say fetish. His eyes dropped to the cash register, where an aged bumper sticker was pasted on. The bumper sticker said:

IF GUNS ARE OUTLAWED, ONLY OUTLAWS

WILL HAVE GUNS

He smiled at Harry and said, "That's very true, you know."

"Sure it is," Harry said. "This cousin of yours..."

"Well, it's kind of a one-upmanship type of thing. He knows how much I like boating and I'll be damned if he didn't up and give me an Evinrude sixty-horsepower motor last Christmas. He sent it by REA express. I gave him a hunting jacket. I felt sort of like a horse's ass."

Harry nodded sympathetically.

"Well, I got a letter from him about six weeks ago, and he sounds just like a kid with a free pass to the circus. It seems that he and about six buddies chipped in together and bought themselves a trip to this place in Mexico, sort of like a free-fire zone--"

"A no-limit hunting preserve?"

"Yeah, that's it." He chuckled a little. "You shoot as much as you want. They stock it, you know. Deer, antelope, bear, bison. Everything."

"Was it Boca Rio?"

"I really don't remember. I think the name was longer than that."

Harry's eyes had gone slightly dreamy. "That guy that just left and myself and two others went to Boca Rio in 1965. I shot a zebra. A goddam zebra! I got it mounted in my game room at home. That was the best time I ever had in my life, bar none. I envy your cousin."

"Well, I talked it over with my wife," he said, "and she said go ahead. We had a very good year at the laundry. I work at the Blue Ribbon Laundry over in Western."

"Yes, I know where that is."

He felt that he could go on talking to Harry all day, for the rest of the year, embroidering the truth and the lies into a beautiful, gleaming tapestry. Let the world go by. Fuck the gas shortage and the high price of beef and the shaky cease-fire. Let there be talk of cousins that never were, right, Fred? Right on, Georgie.

"We got the Central Hospital account this year, as well as the mental institution, and also three new motels."

"Is the Quality Motor Court on Franklin Avenue one of yours?"

"Yes, it is."

"I've stayed there a couple of times," Harry said. "The sheets were always very clean. Funny, you never think about who washes the sheets when you stay at a motel."

"Well, we had a good year. And so I thought, maybe I can get Nick a rifle and a pistol. I know he's always wanted a .44 Magnum, I've heard him mention that one--"

Harry brought the Magnum up and laid it carefully on top of the glass case. He picked it up. He liked the heft of it. It felt like business.

He put it back down on the glass case.

"The chambering on that--" Harry began.

He laughed and held up a hand. "Don't sell me. I'm sold. An ignoramus always sells himself. How much ammunition should I get with that?"

Harry shrugged. "Get him ten boxes, why don't you? He can always get more. The price on that gun is two-eighty-nine plus tax, but I'm going to give it to you for two-eighty, ammo thrown in. How's that?"

"Super," he said, meaning it. And then, because something more seemed required, he added: "It's a handsome piece."

"If it's Boca Rio, he'll put it to good use."

"Now the rifle--"

"What does he have?"

He shrugged and spread his hands. "I'm sorry. I really don't know. Two or three shotguns, and something he calls an auto-loader--"

"Remington?" Harry asked him so quickly that he felt afraid; it was as if he had been walking in waist-deep water that had suddenly shelved off.

"I think it was. I could be wrong."

"Remington makes the best," Harry said, and nodded, putting him at ease again. "How high do you want to go?"

"Well, I'll be honest with you. The motor probably cost him four hundred. I'd like to go at least five. Six hundred tops."

"You and this cousin really get along, don't you?"

"We grew up together," he said sincerely. "I think I'd give my right arm to Nick, if he wanted it."

"Well, let me show you something," Harry said. He picked a key out of the bundle on his ring and went to one of the glass cabinets. He opened it, climbed up on a stool, and brought down a long, heavy rifle with an inlaid stock. "This may be a little higher than you want to go, but it's a beautiful gun." Harry handed it to him.

"What is it?"

"That's a four-sixty Weatherbee. Shoots heavier ammunition than I've got here in the place right now. I'd have to order however many rounds you wanted from Chicago. Take about a week. It's a perfectly weighted gun. The muzzle energy on that baby is over eight thousand pounds... like hitting something with an airport limousine. If you hit a buck in the head with it, you'd have to take the tail for a trophy."

"I don't know," he said, sounding dubious even though he had decided he wanted the rifle. "I know Nick wants trophies. That's part of--"

"Sure it is," Harry said, taking the Weatherbee and chambering it. The hole looked big enough to put a carrier pigeon in. "Nobody goes to Boca Rio for meat. So your cousin gut-shoots. With this piece, you don't have to worry about tracking the goddam animal for twelve miles through the high country, the animal suffering the whole time, not to mention you missing dinner. This baby will spread his insides over twenty feet."

"How much?"

"Well, I'll tell you. I can't move it in town. Who wants a freaking anti-tank gun when there's nothing to go after anymore but pheasant? And if you put them on the table, it tastes like you're eating exhaust fumes. It retails for nine-fifty, wholesales for six-thirty. I'd let you have it for seven hundred."

"That comes to... almost a thousand bucks."

"We give a ten percent discount on orders over three hundred dollars. That brings it back to nine." He shrugged. "You give that gun to your cousin, I guarantee he hasn't got one. If he does, I'll buy it back for seven-fifty. I'll put that in writing, that's how sure I am."

"No kidding?"

"Absolutely. Absolutely. Of course, if it's too steep, it's too steep. We can look at some other guns. But if he's a real nut on the subject, I don't have anything else he might not have two of."

"I see." He put a thoughtful expression on his face. "Have you got a telephone?"

"Sure, in the back. Want to call your wife and talk it over?"

"I think I better."

"Sure. Come on."

Harry led him into a cluttered back room. There was a bench and a scarred wooden table littered with gun guts, springs, cleaning fluid, pamphlets, and labeled bottles with lead slugs in them.

"There's the phone," Harry said.

He sat down, picked up the phone, and dialed while Harry went back to get the Magnum and put it in the box.

"Thank you for calling the WDST Weatherphone," the bright, recorded voice said. "This afternoon, snow flurries developing into light snow late this evening--"

"Hi, Mary?" he said. "Listen, I'm in this place called Harvey's Gun Shop. Yeah, about Nicky. I got the pistol we talked about, no problem. There was one right in the showcase. Then the guy showed me this rifle--"

"--clearing by tomorrow afternoon. Lows tonight will be in the thirties, tomorrow in the mid to upper forties. Chance of precipitation tonight--"

"--so what do you think I should do?" Harry was standing in the doorway behind him; he could see the shadow.

"Yeah," he said. "I know that."

"Thank you for dialing the WDST Weatherphone, and be sure to watch Newsplus-Sixty with Bob Reynolds each weekday evening at six o'clock for a weather update. Good-bye."

"You're not kidding, I know it's a lot."

"Thank you for calling the WDST Weatherphone. This afternoon, snow flurries developing into--"

"You sure, honey?"

"Chance of precipitation tonight eighty percent, tomorrow--"

"Well, okay." He turned on the bench, grinned at Harry, and made a circle with his right thumb and forefinger. "He's a nice guy. Said he'd guarantee me Nick didn't have one."

"--by tomorrow afternoon. Lows tonight--"

"I love you too, Mare. Bye." He hung up. Jesus, Freddy, that was neat. It was, George. It was.

He got up. "She says go if I say okay. I do."

Harry smiled. "What are you going to do if he sends you a Thunderbird?"

He smiled back. "Return it unopened."

As they walked back out Harry asked, "Check or charge?"

"American Express, if it's okay."

"Good as gold."

He got his card out. On the back, written on the special strip, it said:

BARTON GEORGE DAWES

"You're sure the shells will come in time for me to ship everything to Fred?"

Harry looked up from the credit blank. "Fred?"

His smile expanded. "Nick is Fred and Fred is Nick," he said. "Nicholas Frederic Adams. It's kind of a joke about the name. From when we were kids."

"Oh." He smiled politely as people do when the joke is in and they are out. "You want to sign here?"

He signed.

Harry took another book out from under the counter, a heavy one with a steel chain punched through the upper left corner, near the binding. "And your name and address here for the federals."

He felt his fingers tighten on the pen. "Sure," he said. "Look at me, I never bought a gun in my life and I'm mad." He wrote his name and address in the book:

Barton George Dawes 1241 Crestallen Street West

"They're into everything," he said.

"This is nothing to what they'd like to do," Harry said.

"I know. You know what I heard on the news the other day? They want a law that says a guy riding on a motorcycle has to wear a mouth protector. A mouth protector, for God's sake. Now is it the government's business if a man wants to chance wrecking his bridgework?"

"Not in my book it isn't," Harry said, putting his book under the counter.

"Or look at that highway extension they're building over in Western. Some snot-nose surveyor says 'It's going through here' and the state sends out a bunch of letters and the letters say, 'Sorry, we're putting the 784 extension through here. You've got a year to find a new house.'?"

"It's a goddam shame."

"Yes, it is. What does 'eminent domain' mean to someone who's lived in the frigging house for twenty years? Made love to their wife there and brought their kid up there and come home to there from trips? That's just something from a law book that they made up so they can crook you better."

Watch it, watch it. But the circuit breaker was a little slow and some of it got through.

"You okay?" Harry asked.

"Yeah. I had one of those submarine sandwiches for lunch, I should know better. They give me gas like hell."

"Try one of these," Harry said, and took a roll of pills from his breast pocket. Written on the outside was:

ROLAIDS

"Thanks," he said. He took one off the top and popped it into his mouth, never minding the bit of lint on it. Look at me, I'm in a TV commercial. Consumes forty-seven times its own weight in excess stomach acid.

"They always do the trick for me," Harry said.

"About the shells--"

"Sure. A week. No more than two. I'll get you seventy rounds."

"Well, why don't you keep these guns right here? Tag them with my name or something. I guess I'm silly, but I really don't want them in the house. That's silly, isn't it?"

"To each his own," Harry said equably.

"Okay. Let me write down my office number. When those bullets come in--"

"Cartridges," Harry interrupted. "Cartridges or shells."

"Cartridges," he said, smiling. "When they come in, give me a ring. I'll pick the guns up and make arrangements about shipping them. REA will ship guns, won't they?"

"Sure. Your cousin will have to sign for them on the other end, that's all."

He wrote his name on one of Harry's business cards. The card said:

Harold Swinnerton

849-6330

HARVEY'S GUN SHOP

Ammunition

Antique Guns

"Say," he said. "If you're Harold, who's Harvey?"

"Harvey was my brother. He died eight years ago."

"I'm sorry."

"We all were. He came down here one day, opened up, cleared the cash register, and then dropped dead of a heart attack. One of the sweetest men you'd ever want to meet. He could bring down a deer at two hundred yards."

He reached over the counter and they shook.

"I'll call," Harry promised.

"Take good care."

He went out into the snow again, past SHAKY CEASE-FIRE HOLDS. It was coming down a little harder now, and his gloves were home.

What were you doing in there, George?

Thump, the circuit breaker.

By the time he got to the bus stop, it might have been an incident he had read about somewhere. No more.

• - •

Crestallen Street West was a long, downward-curving street that had enjoyed a fair view of the park and an excellent view of the river until progress had intervened in the shape of a high-rise housing development. It had gone up on Westfield Avenue two years before and had blocked most of the view.

Number 1241 was a split-level ranch house with a one-car garage beside it. There was a long front yard, now barren and waiting for snow--real snow--to cover it. The driveway was asphalt, freshly hot-topped the previous spring.

He went inside and heard the TV, the new Zenith cabinet model they had gotten in the summer. There was a motorized antenna on the roof which he had put up himself. She had not wanted that, because of what was supposed to happen, but he had insisted. If it could be mounted, he had reasoned, it could be dismounted when they moved. Bart, don't be silly. It's just extra expense... just extra work for you. But he had outlasted her, and finally she said she would "humor" him. That's what she said on the rare occasions when he cared enough about something to force it through the sticky molasses of her arguments. All right, Bart. This time I'll "humor" you.

At the moment she was watching Merv Griffin chat with a celebrity. The celebrity was Lorne Greene, who was talking about his new police series, Griff. Lorne was telling Merv how much he loved doing the show. Soon a black singer (a negress songstress, he thought) who no one had ever heard of would come on and sing a song. "I Left My Heart in San Francisco," perhaps.

"Hi, Mary," he called.

"Hi, Bart."

Mail on the table. He flipped through it. A letter to Mary from her slightly psycho sister in Baltimore. A Gulf credit card bill--thirty-eight dollars. A checking account statement: 49 debits, 9 credits, $954.47 balance. A good thing he had used American Express at the gun shop.

"The coffee's hot," Mary called. "Or did you want a drink?"

"Drink," he said. "I'll get it."

Three other pieces of mail: An overdue notice from the library. Facing the Lions, by Tom Wicker. Wicker had spoken to a Rotary luncheon a month ago, and he was the best speaker they'd had in years.

A personal note from Stephan Ordner, one of the managerial bigwigs in Amroco, the corporation that now owned the Blue Ribbon almost outright. Ordner wanted him to drop by and discuss the Waterford deal--would Friday be okay, or was he planning to be away for Thanksgiving? If so, give a call. If not, bring Mary. Carla always enjoyed the chance to see Mary and blah-blah and bullshit-bullshit, etc., et al.

And another letter from the highway department.

He stood looking down at it for a long time in the gray afternoon light that fell through the windows, and then put all the mail on the sideboard. He made himself a scotch-rocks and took it into the living room.

Merv was still chatting with Lorne. The color on the new Zenith was more than good; it was nearly occult. He thought, if our ICBM's are as good as our color TV, there's going to be a hell of a big bang someday. Lorne's hair was silver, the most impossible shade of silver conceivable. Boy, I'll snatch you bald-headed, he thought, and chuckled. It had been one of his mother's favorite sayings. He could not say why the image of Lorne Greene bald-headed was so amusing. A light attack of belated hysteria over the gun shop episode, maybe.

Mary looked up, a smile on her lips. "A funny?"

"Nothing," he said. "Just my thinks."

He sat down beside her and pecked her cheek. She was a tall woman, thirty-eight now, and at that crisis of looks where early prettiness is deciding what to be in middle age. Her skin was very good, her breasts small and not apt to sag much. She ate a lot, but her conveyor-belt metabolism kept her slim. She would not be apt to tremble at the thought of wearing a bathing suit on a public beach ten years from now, no matter how the gods decided to dispose of the rest of her case. It made him conscious of his own slight bay window. Hell, Freddy, every executive has a bay window. It's a success symbol, like a Delta 88. That's right, George. Watch the old ticker and the cancer-sticks and you'll see eighty yet.

"How did it go today?" she asked.

"Good."

"Did you get out to the new plant in Waterford?"

"Not today."

He hadn't been out to Waterford since late October. Ordner knew it--a little bird must have told him--and hence the note. The site of the new plant was a vacated textile mill, and the smart mick realtor handling the deal kept calling him. We have to close this thing out, the smart mick realtor kept telling him. You people aren't the only ones over in Westside with your fingers in the crack. I'm going as fast as I can, he told the smart mick realtor. You'll have to be patient.

"What about the place in Crescent?" she asked him. "The brick house."

"It's out of our reach," he said. "They're asking forty-eight thousand."

"For that place?" she asked indignantly. "Highway robbery!"

"It sure is." He took a deep swallow of his drink. "What did old Bea from Baltimore have to say?"

"The usual. She's into consciousness-raising group hydrotherapy now. Isn't that a sketch? Bart--"

"It sure is," he said quickly.

"Bart, we've got to get moving on this. January twentieth is coming, and we'll be out in the street."

"I'm going as fast as I can," he said. "We just have to be patient."

"That little Colonial on Union Street--"

"--is sold," he finished, and drained his drink.

"Well, that's what I mean," she said, exasperated. "That would have been perfectly fine for the two of us. With the money the city's allowing us for this house and lot, we could have been ahead."

"I didn't like it."

"You don't seem to like very much these days," she said with surprising bitterness. "He didn't like it," she told the TV. The negress songstress was on now, singing "Alfie."

"Mary, I'm doing all I can."

She turned and looked at him earnestly. "Bart, I know how you feel about this house--"

"No you don't," he said. "Not at all."

Copyright © 1981 by Stephen King

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details