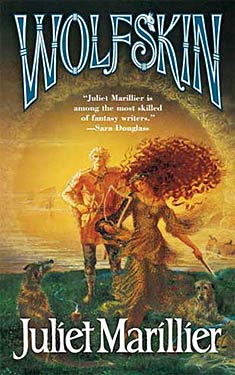

Wolfskin

| Author: | Juliet Marillier |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2003 Pan Macmillan, 2002 |

| Series: | Children of the Light Isles: Book 1 |

|

1. Wolfskin |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

All young Eyvind ever wanted was to become a great Viking warrior--a Wolfskin--and perform honorable deeds out in the name of his War fathergod, Thor. He can think of no future more glorious. And the chance to make it happen is his when his older brother Ulf is brought the tale of a magical land across the sea, a place where men with courage could go to conquer a land and bring glory to themselves. They set out to find this fabled land and discover a windswept and barren place, but one filled with unexpected beauty and hidden treasures... and a people who are willing to share their bounty.

Ulf's new settlement begins in harmony with the natives of the isles led by the gentle king Engus. And Eyvind finds a treasure of his own in the young Nessa, niece of the king, seer, and princess. His life will change forever as she claims his heart for her own.

But someone has come along to this new land who is not what he seems. Eyvind's heartfriend, Somerled, the strange and lonely boy Eyvind befriended so long ago has a secret--and his own plans for the future. The blood oath that they swore in childhood binds them in lifelong loyalty, and Somerled is calling in the debt of honor. What he asks might just doom Evyind to kill the only thing that he has ever truly loved.

Will the price of honor create the destruction of all that Eyvind holds dear?

Critically acclaimed fantasist Juliet Marillier returns with the start of a new fantasy saga, a wonderful love story set amidst high adventure. Wolfskin is a lush tale of the clash between the warlike Norsemen and the mysterious and magical people who live at the top of the world in the land that will become Scotland--and it is the story of the man and woman who forge a bond that will remake their world.

Excerpt

ONE

Winter bites hard in Rogaland. Sodden thatch shudders under its blanket of snow. Within the earthen barns sheep shiver and huddle, their breath small clouds. A man can lose himself in the drifts between byre and longhouse, and not be found again until the spring thaw. The pristine shroud that covers him is deep, but his long sleep is deeper still. In such a season the ice forms black and hard on lake and stream. For some, it is a good time: merchants whip their horses fast along the gleaming surface of the waterways, sledges piled high with pelts of squirrel and winter hare, with sealskins and oil and walrus tusks, with salt fish and fine embroidery. Boys dart across the river on their bone skates, quick as swallows, voices echoing away to lose themselves among the pale twigs of the winter birches.

It was Yuletide, and today there was no skating. The wind screamed around the temple, demanding entry through any chink or cranny its piercing fingers might discover. The timbers creaked and groaned in response, but held firm. So far, the roof had not leaked. Just as well he'd climbed up and shifted some of the weight off the shingles, Eyvind thought. The place would be full to bursting for the midwinter sacrifice.

Folk were already streaming into the valley, coming by sledge and on foot, on skis or skates, old men carried on their sons' backs, old women pulled on hurdles by red-faced children or panting dogs. The wind died down, as if holding its breath in honor of the occasion, but a new storm was coming. Dark clouds built in the west.

Eyvind had been working hard. The temple was on his mother's land, though shared by all in the surrounding district, so the burden of preparation fell squarely on the household at Hammarsby. He'd spent the morning chopping wood, stacking the pungent-smelling logs by the central hearth, making and banking the fire. It was nearly time for the ceremony; he should stir the coals now and put on more fuel. The white goat could be heard outside, bleating, plaintively. His sisters had swept the stone floor clean and stripped the cobwebs from the rooftrees, while his mother, Ingi, polished the bronze surfaces of ritual knives and bowls to a bright, sunny sheen. These now lay ready on the altar at the temple's northern end. Cold light pierced the shingled roof above the hearth. From the altar, Thor's image stared down at Eyvind. Bushy browed, full-bearded, the god's wooden features held an expression of ferocious challenge. In his iron-gloved right hand he gripped the war hammer, Mjollnir; his left was held across his chest, to signify the making of some vow. Eyvind stared back, meeting Thor's gaze without blinking, and his own hand moved to his breast as if returning a pledge of allegiance. Till death, he thought Thor was saying, and he whispered his answer, "Till death and beyond."

The air was crisp and chill, the sacred space clean and quiet in the cold winter light. Later there would be a press of bodies in the temple, and it would be all too warm. As Eyvind used the iron poker to stir the embers to life, there was a sound from the entry behind him. He turned to see a tall, broad figure striding toward him, hair and beard touched to dark gold by the glow of the rekindled fire.

"Well, well, little brother! I swear you've doubled in size since the harvest!"

Eyvind felt a huge grin spreading across his face. "Eirik! You're home! Tell me where you've been, and what you've been doing! I want to hear everything!"

His brother seized him in a brief, hard embrace, then stretched out his hands to warm them before the flames.

"Later, later," he laughed. "Time enough for all that after the sacrifice. We'll have many tales, for I do not come alone."

"Hakon is here too?" Eyvind asked eagerly. He admired Hakon almost as much as he did Eirik himself, for his brother's friend had earned his wolfskin at not quite sixteen, which was generally thought to be some sort of record.

"Hakon, and others," Eirik said, suddenly serious. "The Jarl's kinsman, Ulf, is with us; a fine man, and a friend of ours. He's brought his young brother and several of his household. They're on their way to Jarl Magnus's court. Ulf has a wish for some delicate silverwork, I think to impress a lady. I made it known to him that our sister's husband is skilled in this craft. They will spend some nights here, in any event; the storm looks likely to prevent further travel for a little. The Jarl himself was urgent for home. He has a new son, bred when we came back from the spring viking; he is gone ahead, but we have time before we must join him. He will not set out again before spring's seeding is attended to." He glanced at his brother, and his tone changed. "Eyvind? I've a favor to ask you."

"What?"

There were new sounds from outside now, the rapid approach of many folk, voices raised in greeting.

"Later," Eirik said.

Eyvind asked him no further questions, though it was hard to wait. Eirik was his hero. Eirik was a Wolfskin. That was the most glorious calling in the whole world, for surely nothing could surpass the moment when you heard Thor's call to battle ringing in your ears, pulsing in your blood, filling every corner of your being with a red rage that shut out any thought of fear. To charge forward in pure courage, inspired by the god himself--that bold vision tugged at Eyvind's thoughts by day and filled his dreams by night. What matter if a Wolfskin's life were short? Such a warrior, once fallen, would be carried straight to Thor's right hand. One day he himself would pass the test, and become one of that band to which Eirik and Hakon belonged, as had many of Eyvind's kin in times past. The men of Hammarsby had a noble tradition in the Warfather's service. So Eyvind practiced with the bow and with the axe. He ran and climbed, he skated and swam. He shoveled snow and hunted and grew strong, awaiting that day. Eirik's tales kept his dreams alive. Later, perhaps his brother would tell of the autumn viking, the riches plundered, the battles won.

The folk of the district crowded into the temple, along with the men of Jarl Magnus's household, warrior and swineherd side by side. The high seat, its wooden pillars carved with many small creatures, was allocated to Ulf, kinsman of the Jarl, and by him stood the two Wolfskins, gold-bearded Eirik and the taller, hawk-featured Hakon. Each wore his short cloak of shaggy fur, fastened on the shoulder with an ornate silver brooch. Both were well armed: Eirik had the lethal skeggox, or hewing axe, on his back, and Hakon bore a fine sword, its hilt plated with copper. The nobleman, Ulf, was young: not so much older than Eirik himself, Eyvind thought. He had many folk with him, probably housecarls called into service for the autumn viking, with a few richly dressed men who might be part of Jarl Magnus's household elite, or Ulf's own retainers.

Eyvind's eldest brother, Karl, began the ceremony, his solemn features glowing warm in the fire's light. Eyvind was pleased with that fire; the smoke was rising cleanly through the roof opening to disperse in the cold air outside. Karl was no warrior. His choice had been to stay at home and husband the land, his brothers' portions as well as his own. It was a decision that, in hindsight, had been both wise and prudent, for their father, Hallvard Karlsson, had died in his prime, falling nobly in the service of the old Jarl, and leaving Ingi a widow. A young man with a young family of his own, Karl had simply stepped into his father's shoes. Now he and his mother controlled a wide sweep from hilltop to fjord, and commanded great respect in the district. All the same, Eyvind had never understood how his brother could prefer that existence over a life as Thor's warrior. Yet Karl seemed content with what he was.

"Master of storm, tamer of waves, iron-fisted one!" Karl now addressed the god in ringing tones. "Hewer of giants, serpent-slayer, worthiest of warriors! In blood, we honor you! In fire, we salute you! In the shadow time, we seek your protection. May your strong arm guard us on land path and sea path. Smite our enemies and smile on our endeavors."

"Hewer of giants, serpent-slayer, worthiest of warriors!" the assembled folk chanted, and their voices rose with the fire's heat to ring out across the snow-blanketed hills and the dark fir trees, straight to the ears of the god himself. Eyvind joined in the response, his gaze on Thor's staring, formidable eyes. Now Ingi walked slowly around the temple, bearing the ritual arm-ring on a small embroidered cushion. Over many hours a fine smith had wrought there an image of the world tree with its attendant creatures: the serpent Nidhogg at its deepest roots, the noble eagle at its tip, the squirrel Ratatosk scampering between. The pattern went right around the ring; a man could never see the whole of it at one time. They held the sacrifice at first frost, at midwinter and in spring; at all other times, this treasure was well locked away from curious eyes. One hand after another reached out to brush reverently against the gleaming gold: girls' hands still soft and milk-pale, men's hands branded by axe shaft and bowstring, gnarled old hands that knew many winters on the land. All moved to pledge allegiance to the warrior, Thor, and to Odin, who had hung on that selfsame tree in search of wisdom. Even the thralls, clustered like a body of shadows at the far end near the door, stretched out tentative fingers as Ingi passed.

Karl lifted one of the ritual knives from the altar. The goat was struggling, afraid of the crowd and the fire. It seemed to Eyvind that the boy who clutched its neck rope could not hold the creature much longer. If he let go of the rope, the goat would free itself and bolt across the crowded temple in a chaos of hooves and horns. One could not offend the god thus. Eyvind got up and moved forward, relieving the red-faced lad of his charge, soothing the animal with soft words and a careful hand.

"Go on, then," he muttered. Karl raised the sacrificial knife; the firelight shone bright from its bronze blade. Eyvind tightened his grip, forcing the white goat's head back, exposing pink, naked skin where the hair on the throat grew more sparsely. Perhaps sensing the inevitable, the creature made one last desperate surge for freedom. But Eyvind's hands were strong. "Hurry up!" he hissed.

The knife came down, swept across. It should have been easy. Karl was a farmer; slaughtering stock was a routine task for him. But at the vital moment, a bird shrieked harshly above the smoke hole, and somehow the knife slipped sideways, so the blood did not spurt free and scarlet, but only seeped dark against the pure white hair. The goat screamed, and went on screaming. The god was displeased. Karl stood frozen, knowing the omen was bad for them. Thor's eyes were fierce and angry on his back.

"Here," said Eyvind. He took the knife from his brother's fingers, holding the bleeding goat with one hand, fingers twisted in the rope. His legs were on either side of the creature, forcing its agonized form still. This must be done well, now, or there would be failed crops, and sick beasts, and death and defeat feat on the field of war.

"Iron glove guide my blade," Eyvind said, fixing the god's wooden eyes with his own. "In your name, great battle god!"

There was only one way to do such things: hard and swift, straight across, near severing the neck. Fast, accurate, and merciful. How else could a clean kill be made? The screaming ceased. The white goat went limp. Eyvind's sisters held the bronze bowls to catch the blood. There was no telling what Thor thought of the manner of it, but at least Eyvind had done his best. He turned to face the folk, helping Karl to lift the slaughtered goat high so the blood could flow into the bowls. Drops spattered hands, faces, tunics. The altar bore a pattern of red spots; a bloody tear trickled down the face of the god.

I will kill cleanly for you, Eyvind told Thor, but not aloud. Let me be a Wolfskin, and I will be your bravest warrior. Braver than Hakon; braver even than Eirik. All that I am, I will give you. He looked down the temple toward the great assembly of folk, and straight into a pair of eyes so dark, so piercingly intense that his heart seemed to grow still a moment, then lurch painfully back into life. His mind had been on Thor, and blood, and sacrifice, and for a moment he had thought--but no, this was only a boy, a lad of his own age or maybe younger, who stood among the richly dressed entourage of the nobleman, Ulf. But how he stared. He looked at Eyvind as a starving wolf gazes at a man across the wayside fire, wary, fascinated, dangerous. The boy was pale and thin, his brown hair straggling unplaited, his mouth a line. His features were unremarkable save for those feral eyes. Eyvind blinked and looked away.

The girls bore the brimming bowls down the temple, white fingers dipping the blood twigs in, splashing bright crimson on floor and wall, anointing pillar and hearth and door frame, marking each man and woman with the sacrifice. When the bowls were empty, Karl laid them on the altar beside the knives, and the goat was dragged outside to be gutted and prepared for cooking.

"Warfather, we toast you this day of Yule!" Karl raised his great drinking horn. Ingi had passed between the men, pouring the ale with care: one would not wish to offend Thor by spilling any before the toasts were complete. "All hail, great battle leader!" Karl called. They drank.

"All hail mighty Thor, smiter of serpents!" Ulf cried, rising to his feet and lifting his own horn, a fine piece banded in silver. The men echoed his ringing tones and drank again.

"We salute you, crusher of giants!" Eirik's voice was as fierce as his weathered countenance. So the toasts continued, and as they did the patch of sky darkened above the roof aperture, and the inside of the temple glowed strangely in the fire's light. The boy was still staring; now the flames made twin points of brightness in his night-dark eyes. Thunder cracked in the sky above; sudden lightning speared the sky. The storm was on its way.

"Thor is well satisfied," said Eirik. "He calls his greeting to our small assembly; it is a hearty war song. Come, let us move close to the fire, and pass the day with good drink and feasting and tales. A long season we spent on the whale's way, with the wind biting cold through our tunics and never a drop of ale nor a woman's soft form in our sight. We thank the god for guiding us home safely once more. We thank him for our glorious victories, and for the rich spoils we carry. In the growing season, we shall sail forth again to honor him in deeds of courage, but for now, it is good to be home. Let him look kindly on our celebration."

There were many tales told that day, and the more the ale flowed, the more eloquent the telling. There were tales of Thor's valor and Odin's cunning, tales of dragons and heroes. Eyvind sat close to his brother, Eirik, savoring every moment. Of such stuff are dreams made. He wanted Eirik to tell them about the autumn viking: where they had been, what battles they had fought and what plunder they had brought home. But he did not ask. It was enough, for now, that Eirik was here.

That boy was still watching him. Perhaps he was simple in the head. Eyvind tried staring back; the boy met his gaze without blinking. His expression did not change. Eyvind tried smiling politely, though in fact he found the constant scrutiny unsettling. The boy gave a little nod, no more than a tight jerk of the head. He did not smile.

At length, the fire burned lower. The smell of roasted goat flesh lingered. Bellies were comfortably full of the rich meat, and of Ingi's finest oatcakes. The temple was warm with good fellowship. Thor, it seemed, had overlooked the imperfect manner of the ritual, and chosen to smile on them.

Hakon spoke. "I have a tale," he said, "a tale both sorrowful and inspiring, and well suited for Thor's, ears, since it tells of a loyalty which transcended all. It concerns a man named Niall, who fell among cutthroats one night when traveling home from the drinking hall. Niall had on him a purse of silver, with which he planned to buy a fine horse, and ride away to present himself to the Jarl's court. He was not eager to give up his small hoard and his chance to make something of himself, for Niall, like many another young farmer's son, was not rich in lands or worldly possessions. He had worked hard for his silver. So he fought with hands and feet and the small knife that was the only weapon he bore; he fought with all his strength and all his will, and he called on Thor for help from the bottom of his lungs. It was a one-sided struggle, for there were six attackers armed with clubs and sharpened stakes. Niall felt his ribs crack under boot thrusts and his skull ring with blow on blow; his sight grew dim, he saw the night world through a red haze. It occurred to him, through a rising tide of unconsciousness, that this was not a good way to die, snuffed out by scum for a prize they would squabble over and waste and forget, as he himself would be forgotten soon enough. Still he struggled against them, for the will to live burned in him like a small, bright flame.

"Then, abruptly, the kicking stopped. The hands that had gripped his throat, squeezing without mercy, slackened and dropped away. There was a sound of furious activity around him, grunts and oaths, scuffling and a sudden shriek of pain, then retreating footsteps, and silence.

"An arm lifted him up. Odin's bones, every part of his body ached. But he was alive. After all, the gods had not forgotten him.

"'Slowly, slowly, man,' the voice of his rescuer said. 'Here, lean on me. We'd best make our way back to the drinking hall; you're in no fit state to go farther.'

"The man who had saved Niall's life was young, broad, and big-fisted. Still, there was only one of him.

"'How did you do that?' Niall gasped. 'How did you--'

"The stranger chuckled. 'I'm a warrior, friend, and keep a weapon or two about me. Thor calls; I answer. Just as well he called tonight, or your last breath would be gone from your body by now. My name's Brynjolf. Who are you?'

"Niall told him, and later, when his wounds were dressed and the two men were sharing a jug of good ale by the fire, he explained to Brynjolf his plans to present himself to the Jarl, and seek a place in his household.

"'But my money is gone,' Niall said ruefully. 'My silver, all that I had saved--those ruffians took it. Now I have nothing.'

"'You have a friend,' Brynjolf grinned. 'And--let me see--perhaps not all is lost.' He made a play of hunting here and there, in his pockets, in his small knapsack, in the folds of his cloak, until at length, 'Ah' he exclaimed, and drew out the goatskin pouch that held Niall's carefully hoarded silver. Brynjolf shook it, and it jingled. 'This is yours, I think'

"Niall took the pouch wordlessly. He did not look inside, or count the money.

"'You wonder why I did not simply keep this?' Brynjolf queried. 'When I said you had a friend, I spoke the truth. Let us travel on together. I will teach you trick or two, for a man with such scant resources will not get far beyond the safe boundaries of the home farm, unless he learns to defend himself.'

"So Niall and Brynjolf became the best of comrades, and on the way to the Jarl's court they shared may adventures. And they swore an oath, an oath deep and solemn, for each scored his arm with a knife until the blood ran forth, dripping on the earth, and they set their forearms together and swore on their mingled blood that they would be as brothers from that day on. They vowed they would put this bond before all other loyalties, to support one another, to stand against the other's enemies even until death. This oath they swore in Thor's name, and the god smiled on them.

"The years passed. Brynjolf joined the Jarl's personal guard, and acquitted himself with great valor. Niall learned to use the sword and the axe, but he was not cut out to be a warrior. In time, he discovered he had a talent for making verses, and this pleased the Jarl mightily, for men of power love to hear the tales of their own great deeds told in fine, clever words. So, remarkably, Niall became a skald, and told his tales at gatherings of influential men, while his friend journeyed forth with the Jarl's fleet in spring and in autumn, to raid along the coast of Fries-land and Saxony. When Brynjolf returned, they would drink together, and laugh, and tell their tales, and they would pledge their brotherhood anew, this time in strong ale.

"One summer Brynjolf came home with shadowed eyes and gaunt features. Late one night he told Niall a terrible story. While Bryjolf had been away, his family had perished in a hall-buring: father, mother, sister and young brothers. A dispute had festered over boundaries; this had grown to skirmishes, and then to killing. Late one night, when all the household slept, the neighbor's men had surrounded the longhouse of Brynjolf's father, and torched it. In the morning, walking among the blackened ruins of the place, folk swore they could still hear screaming, though all were dead, even the babies. All this, while Brynjolf himself was far away on the sea, not knowing. When he set foot on shore, they told him, and saw his amiable face become a mask of hate.

"Niall could think of nothing to say.

"'I will find the man who did this,' Brynjolf muttered, cold-eyed, 'and he will pay in kind. Such an evil deed invites no less. He is far north in Frosta, and I am bound southward this summer, but he and his are marked for death at my hand'

"Niall nodded and said nothing, and before seven days had passed, his friend was off again on the Jarl's business. Niall put the terrible tale in the back of his mind.

"It was a mild summer and the earth wore her loveliest gown. Flowers filled the meadows with soft color and sweet perfume, crops grew thick and healthy, fruit ripened on the bushes. And Niall fell in love. There were many visitors to the court: noblemen, dignitaries, emissaries from far countries, landowners seeking favors. There was a man called Hrolf, who had come there to speak of trading matters, bringing his daughter. Every evening, folk gathered in the hall, and in the firelight Niall told his tales and sang his verses. The girl sat among the women of the household, and he thought her a shining pearl among plain stones, a sweet dove among barnyard chickens. Her name was Thora, and Niall's heart was quite lost to her snow-pale skin and flax-gold hair, her demure features and warm, blue eyes. As he sang, he knew she watched him, and once or twice he caught a smile.

"Niall was in luck. He was shy, and Thora was shyer. But the Jarl favored his skald, and spoke to Hrolf on Niall's behalf, and at length, her father agreed to consider the possibility of a marriage in a year or so when the girl was sixteen. For now, it would not hurt the young man to wait They might exchange gifts. Next summer, Niall could visit them in the north. All things in good time.

"The lovers snatched moments together, for all the watchful care of Thora's keepers: kisses in shadowed hallways, one lovely meeting at dusk in the garden, hidden by hedges of flowering thorn. They sang together softly; they taught each other verses of love. Niall told Thora she had a voice like a lark; she giggled and put her arms around him, and he thought he might die of joy and of anticipation. Then summer drew to a close, and Hrolf took his daughter home.

"Brynjolf did not go on the autumn viking that year. He excused himself from court and traveled north, and with him he took his blood brother; Niall the poet. To distant Frosta they journeyed, and by the wayside, they acquired two large silent companions, men with scarred faces, whose empty eyes filled Niall with dread. There was no need for Brynjolf to tell him where they were going, or for what purpose. It was a quest for vengeance, and Niall's oath bound him to it. He fixed his thoughts on the summer, and on his sweet Thora. Life would be good: the comforts of the Jarl's court, the satisfaction of exercising his craft, the joys of marriage. He must simply do what had to be done here, and put it behind him, for there was a rosy future ahead.

"They moved through deep woodlands by night. At the forest fringe, Brynjolf halted them with a hand. Not far below them lay a darkened longhouse, a thread of smoke still rising from the chimney. The folk were abed; a half moon touched the roof thatch with silver and glinted on bucket set neatly by but well.

"'Draw your swords,' whispered Brynjolf. 'Not one must escape: not man, woman nor child. Go in quickly. There may be dogs.'

"Then they lit torched from the one Brynjolf had carried, and with naked sword in hand, each ran to a different side of the building. Niall's was the north. He saw the flare of dry wattles catching to east and west; so far, the dogs were silent. But it seemed not all there slept. From within the darkened house, close to the place where he stood frozen, clutching his flaming brand, came the sound of a girl singing. She sang very softly, in a voice like a lark's, a little song know only to a pair of lovers who had crafted it one summer's eve in a sheltered garden."

As Hakon recounted his tale, there was a deathly silence in the temple. Some of his audience had seen this coming, knowing the way of such tales, yet still the horror of it gripped them.

"What could he do?" asked Hakon. "Thora was there, in the house, and already flames rose on three sides of the building, hungry for wattles and timber and human flesh. She was the daughter of Brynjolf's enemy, the man who had cruelly slaughtered his friend's entire family. Niall loved her. And he had sworn a blood oath to the man who had saved his life. 'Let me die this day for what I do,' muttered Niall. 'Let my eyes be blind and my ears deaf. Let my heart break now, and my body be consumed in this conflagration.' And he reached out with his flaming torch, and set fire to the wattles on the northern side.

"It was a vengeance full and complete. The flames consumed all; there was no need for swords. When it was over, Brynjolf paid off the hired men, and he and Niall went homeward. Brynjolf thought Niall a little silent, a little withdrawn. Still, reasoned the warrior, the skald led a protected life. He was not accustomed to acts of violence, to the daily witnessing of sudden death. Indeed, if it had not been for Brynjolf's own intervention, Niall would not have survived to journey forth from the home farm and become a man of wealth and status.

"They returned to the Jarl's court. For a long time, Niall made no more poems. He pleaded illness; the Jarl allowed him time. Brynjolf was somewhat concerned. Once or twice he asked Niall what was wrong, and Niall replied, nothing. Brynjolf concluded there was a girl in it somewhere. Folk had suggested that Niall had a sweetheart, and had planned to marry, but now there was no talk of that. Perhaps she had rejected him. That would explain his pallor, and his silence.

"Winter passed. Brynjolf went away on the spring viking, and Niall made verses again. Over the years, and he had a very long life, he made many verses. He never married; they said he was wed to his craft. But after that summer, his poems changed. There was a darkness in them, a deep sorrow that shadowed even the boldest and most heroic tale of war, that lingered in the heartiest tale of good fellowship. Niall's stories made folk shiver; they made folk weep.

"A young skald asked him once why he told always of sadness, of terrible choices, of errors and waste. And Niall replied, 'A lifetime is not sufficient to sing a man's greif. You will learn that, before you are old.' Yet, when Niall died as a bearded ancient, Thor had him carried straight to Valholl, as if he were a dauntless warrior. The god honors the faithful. And who is more true than a man who keeps his oath, though it breaks his heart?"

After Hakon had finished speaking, nobody said anything for a long while. Then one of the older warriors spoke quietly.

"You tell this story well, Wolfskin. And it is indeed apt: a tale well suited for this ritual day. Which of us, I wonder, would have the strength to act as this man did? And yet, undoubtedly, he did as Thor would wish. There is no bond that can transcend an oath between men, sworn in blood, save a vow to the god himself."

There was a general murmur of agreement. Glancing at his mother, Eyvind thought she was about to speak, but she closed her mouth again without uttering a word.

"It is fine and sobering tale," Karl said, "and reminds us that an oath must not be sworn lightly. Such a tale sets a tear in the eye of a strong man. My friends, the light will be fading soon, and some have far to travel."

"Indeed," said Eirik, rising to his feet. "It grows late and we must depart. I and my companions have journeyed far this day; we return now to my mother's home, to rest there awhile. You'd best be on your way while it is still light, for the storm is close at hand. There will be fresh snow by morning."

* * *

It was as well the longhouse at Hammarsby was spacious and comfortably appointed. A large party made its way there, arriving just before the wind began to howl in earnest, and the first swirling eddies of snow to descend. The nobleman Ulf and his richly dressed companions, the two Wolfskins and a number of other folk of the Jarl's household gathered at Ingi's home. The wind chased Eyvind in the small back doorway; he had arrived somewhat later than the others, after staying behind to make sure the fire was safely quenched and the temple shuttered against the storm. The instant he came inside he saw the boy standing in the shadows by the wall, arms folded around himself. There was nobody else in sight; they would all be gathered close to the hearth's warmth. Eyvind spoke politely, since he could hardly pretend the strange lad was not there.

"Thor's hammer, what a wind! My name's Eyvind. You're welcome here."

The boy gave a stiff nod.

Eyvind tried again. "Looks like you'll be staying with us a few days. There'll be heavy snow tonight; you'd never get out, even on skis."

There was a short pause. Then the boy said, "Why did it scream?"

Now it was Eyvind's turn to stare. "What?" he asked after a moment.

"The goat. Why did it scream?"

What sort of question was that? "I--because the sacrifice wasn't done properly," Eyvind said. "It screamed because the knife slipped. It was hurt and frightened."

The boy nodded gravely. "I see," he said.

Eyvind drew a deep breath. "Come on," he said, "it's warmer by the fire, and the others, my brother and Hakon, and the guests. My brother is Eirik. He's a Wolfskin." There was a satisfaction in telling people this.

"I know," said the boy. "Eirik Hallvardsson. And there's another brother, Karl, who is not a Wolfskin. Your mother is Ingi, a window. Your father died in battle."

Eyvind looked at him. "How do you know that?" he asked.

"If I'm to stay here until the summer, I must be well prepared," the boy said flatly. "It's foolish not to find out all you can."

Eyvind was mute.

"Your brother didn't tell you," said the boy. "I see that. I have a brother too, one who has an inclination to build ships and sail off to islands full of savages. He doesn't want me, I'm to stay here and learn what other boys do with their time. You're supposed to teach me."

Eyvind gaped. If this was the favor his brother had spoken of, it was pretty one-sided. The boy was pale and scrawny; he looked as if he'd never held a sword or a bow in his life, he spoke so strangely you could hardly understand what he meant, and he stared all the time. What was Eirik thinking?

"I'm not going to say sorry." The boy was looking at the floor now, his voice a little uneven. "It wasn't my idea."

There was a brief silence. "It's all right," Eyvind said with an effort. "It's rather a surprise, that's all. Do you know how to fight?"

The boy shook his head. "Now the sort of fight you mean, with knives or fists."

"What other kind is there?" Eyvind asked, puzzled.

There was the faintest trace of a smile on the boy's thin lips. "Maybe that's what I'm supposed to teach you," he said.

False courage, though Eyvind. It must be very hard, frightening even, if you were a weakling and a bit simple in the head, and had no sort of skills at all, to be dumped in a strange household with the kinsfolk of a Wolfskin. No wonder the lad pretended to some sort of secret knowledge; no wonder he tried to look superior.

"Don't worry," Eyvind said magnanimously. "I'll look after you. Don't worry about anything." He put out a hand, and the boy clasped it for an instant and let go. He wasn't smiling, not exactly, but at least that blank stare was gone. His hand was cold as a frozen fish.

"Come on," Eyvind urged. "I'm for a warm fire and a drink of ale." He led the way past the sleeping quarters, which opened to left and right of the central passageway. Though it was growing dark, none of the household was yet abed. The days were short, the time after sundown spent in tales by the hearth, and in what crafts could be plied indoors by the light of seal-oil lamps. Ingi and her daughters were noted for their embroidery; Karl carved goblets and candleholders and cunning small creatures from pale soapstone. Solveig's husband Bjarni was scratching away on his pattern board, making designs which by daylight he would transform into clasps and rings and brooches of intricate silverwork. Helga's husband was away, for the hard winter meant a swift passage by ice roads to the great trading fairs in Kaupang and far-off Birka. In summer, he would take ship for ports still more distant, traveling far east. At Novgorod you could get spices and silks from the hot southern lands, fine honey, Arab silver, and slaves. Ingi herself had a thrall-woman with jutting cheekbones and dark, slanting eyes, who shivered through the winter, wrapped in heavy shawls. This exotic slave had two small children; curiously, neither resembled Oksana herself. Indeed, with their wide blue eyes and golden hair, these infants could have been part of Ingi's own family.

Faces turned toward the boys as they emerged from the hallway, Eyvind leading, the other behind like a smaller shadow.

"Ah," said Eirik with a look in his eyes that mingled relief and apology, "You found Somerled, then."

Eyvind nodded, and went to sit on the worn sheepskins that covered the floor by the hearth. The boy hovered, hesitant. Somerled. So that was his name. Eyvind glanced up, jerked his head a little. Noiselessly, the boy moved to settle cross-legged at his side.

"Good," whispered Eyvind. "There's nothing to be afraid of."

Ulf had told no tales at the feasting. He seemed a cautious sort of man, dark-bearded, neat-featured, and watchful. But in the quite of the home hearth, as the family sat about the fire with ale cups in hand, he seemed to relax, and began to talk. It then became evident that Ulf was a man with a mission. He wanted to build a ship: not an ordinary longship, but a vessel such as no man had seen before in all Norway. And in it he intended to journey where no man of Norway had yet traveled; he would sail to a place that might be real, or that might be no more than fable. With his soft voice and the glow in his dark eyes, he drew them all into his dream.

"There is a land out in the western sea," he told them, "a land my father heard tell of from a man he met the markets in Birka, beyond the eastern mountains in the land of the Svear. This fellow had traveled far, from wild Pictland southward through Britain, by sea to the Frankish realms and north to Saxony. From there he took ship to the Baltic markets with his precious cargo: boards set with jewels and fine enamelwork, which once housed books in a temple of the Christian faith. The books themselves were discarded, but the bindings were indeed things of wonder, and would make this man rich if he were not slaughtered in the darkness first for what he carried. He had made a long journey. Pictland is a bleak territory, inhabited by wild people. But from its northern shores, said this traveler, far out in the trackless ocean, can be reached a place of warm sea currents, of verdant islands and sheltered waterways, a realm of peaceful bays and gentle grazing lands. The crossing is dangerous from those parts in the vessels they use, simple skin curraghs for the most part. It is a longer path from Rogaland, but not so long that it could not be done, if a ship were built strongly enough to withstand the journey. The news of such a place inspired my father. He yearned to travel there. That he was prevented from pursuing it is a lifelong regret for him."

"You plan to undertake an expedition to those parts yourself, my lord?" Karl asked politely.

Ulf gave a rueful smile. "I make it plain enough, I suppose, that I have inherited my father's obsession. Such a venture would be fraught with risk. But one day I will do it."

"You'd need a fine boat," Eyvind said, hoping he did not speak out of turn. "If it's a rough crossing from that southern shore, it could be a rougher one from Rogaland, all the way. It's a brave man who would voyage beyond the skerry-guard, straight out into open seas: into the unknown."

The Jarl's Kinsman looked at him with sudden interest. "I'll build a boat, lad," he said quietly. "She'll be a queen among vessels, sleek, graceful, the equal of any of our shore-raiding ships for speed and maneuverability, but strong enough for a long voyage in open water. I'll gather the best shipwrights in all Norway to work for me, and when the boat is ready, the finest warriors in all Norway will travel with me. I'll see that land while I'm still young, and if it pleases me, I'll take a piece of it in my father's name."

The eyes of every man in the hall had kindled with enthusiasm, for when Ulf spoke of this dream there was something in his face, his voice, his bearing that seized the spirit and quickened the heart. It was plain this soft-spoken, reserved man was that rare phenomenon: a true leader.

"It'd cost you an arm and a leg," Eirik observed. "Ships, crew, supplies."

"You doubt my ability to carry this out?" Ulf's expression was suddenly grim.

"Indeed no," Eirik said calmly. "I do not. But even a Wolfskin likes to know what he's getting into."

Ulf smiled. "Ah," he said, "I have one taker, then."

"Two." Hakon spoke from his place on the nobleman's other side. "You are a man of vision, my lord. A new horizon, an unknown land: what warrior could fail to be drawn by that? I will go, if you'll have me."

Ulf nodded. "I hope Magnus may be prepared to support us, and to release you both. It won't be tomorrow, my friends, or next season. As you say, there must be resources for such an undertaking. I need time. Still, I see the great ship in my mind, her sails full-bellied in the east wind, her prow dragon-crested; I taste the salt air of that place even now."

"The expedition is a fine prospect and stirring to the spirit," Eirik said. "Good farming land is scarce enough here; a man with many sons leaves scant portions. There's more than one likely lad who would jump at the chance to settle in such a place, if it's indeed as verdant and sheltered as you say. You'll find plenty of takers before you go, I think."

"As to that," said Ulf, "I winnow my wheat once, twice, three times before I make my bread, for I am slow to trust. I will not sink all my resources in such a venture to have it end with a knife in the back."

"Wisely spoken." To everyone's surprise, it was the boy Somerled who spoke. "My brother is a man with a curse on him; he needs to be rather more cautious than most."

Ulf was regarding his brother with a look of distaste. "Enough, Somerled," he said. "We will not speak of that here at this peaceful hearth."

"It's a good curse." The boy went on as if Ulf had not spoken. "A kind of riddle. I like riddles. It goes like this:

* * *

"Pinioned in flowers pf straw

cloaked in a mackerel's shroud

His dirge a seabird's cry

Neither on land or water does he perish

Ulf, far-seeker, dreamer of dreams

Yet tastes the salt sea, watches the wild sky

By neither friend nor foe

Slain with his hope before his eyes."

* * *

There was silence. It was plain to all that Ulf had not wanted this spoken aloud.

"A strange verse indeed," Karl said after a little. "What does it mean?"

"As to that," Ulf said soberly, rising to his feet, "it seems nonsense. If a man is neither on land nor water, where can he be? Flying like an albatross? An old woman spoke such a verse over me when I was in the cradle, that is all. Folk make much of it, but it seems to me a man must live his life without always looking over his shoulder. If some strange fate overtakes me and proves these words true, so be it. I will not live in fear of them. Indeed, I would prefer to forget them." He frowned at Somerled.

After that, the talk turned to safer matters, and soon enough it was bedtime. Because Somerled was a nobleman's brother, and a visitor, the two lads who shared Eyvind's small sleeping area had to move, and Somerled was given their space. It meant there was more room, which Eyvind appreciated. He was growing taller; his toes were making holes in his boots and his wrists stuck out of his shirtsleeves. Somerled was small, and slept neatly, rolled tight in a blanket, still as if dead. On the other hand, he had a gift for banishing other people's sleep. That first night, just as Eyvind, comfortably tired from the long day's work and warmed by the strong ale, hovered on the verge of slumber, Somerled asked another question.

"Do you think she screamed?" he inquired.

Eyvind's eyes snapped open. "What Who?" he asked testily.

"You know. That girl, Thora. Do you think she screamed, when she started to burn?"

"Leave it, will you?" growled Eyvind, too annoyed to think of good manners. He had almost managed to forget the story of Niall and Brynjolf in the warmth and fellowship of the longhouse. Now it came back to him in all its painful and confusing detail.

"I should think she did," Somerled said tranquilly, answering his own question. "I wonder what Niall felt when he heard the singing change. I wonder how it takes you, that moment when everything turns to shadows."

Eyvind pulled his blanket over his head and stuck his fingers in his ears. But Somerled was finished; before you could count to fifty he was snoring peacefully. It was Eyvind who tossed and turned, his mind flooded with dark images.

* * *

Eirik did offer his brother a kind of apology before he left, and an explanation. Ulf had been concerned about Somerled, Eirik said. The boy had never been quite the same since he witnessed his own mother's death. His father was old and bitter and had not been kind to this young son, and the household had taken its lead from the master. Ulf had been away a long time, and had returned to a home on the brink of self-destruction. Powerful chieftains gathered close, hovering as scavengers do, awaiting the moment of death. There was a need to take control quickly, to undo the ill his father's mismanagement had created before lands and status were quite lost. But Ulf wanted his half-brother-Somerled was the child of a second marriage--out of the place first. The boy had seen too much already, and was behaving very strangely. He spent all his time alone, he didn't seem to trust anyone, and he never wanted to play games, or ride, or wrestle, as a boy should. Indeed, Ulf scarcely knew what to do with him, and Somerled had made it no easier by refusing to talk. The boy was as tightly closed as a limpet.

So Ulf had brought Somerled back to the south, and sought out his friend, Eirik the Wolfskin, a man known to have a great deal of common sense. Eirik heard Ulf's tale and made an offer. He had a brother of about Somerled's age. He thought his mother would not object to another lad around the house. Why didn't Ulf leave the boy with them, at least until the summer?

"I must confess," Eirik told Eyvind with a half-smile, "I welcomed the chance this gave me to return here for a little. And Ulf thought it an excellent idea. Somerled has not had the company of other children, and it shows in his demeanor. He seems unnaturally shy; I've hardly heard him utter word."

Eyvind grimaced. "He talks to me," he said.

"Good," said Eirik. "That's a start. I've a great deal of respect for Ulf; he's a man of vision and balance. I was glad to be able to help him."

"Eirik?"

"What?"

"When can I do the trial? How much longer? I'm nearly twelve now, and I've been practicing hard. I can take a hare neatly at two hundred paces, and swim across the Serpent's Neck underwater without coming up for air. How long must I wait?"

"A while yet," said Eirik. "Four more summers at least, I think"

Eyvind's heart plummeted. He would not speak his disappointment, for Thor did not look favorably on such signs of weakness.

"But maybe not so long," his brother added, smiling. "You are almost a man. What boy has such great hands and feet? And you're nearly as tall as I am, for all I have six years' advantage. Perhaps only three summers."

That was good news and bad news. Eirik thought him nearly grown up; that made his cheeks flush with pride. But three years, three whole years before he got the chance to prove himself? How could he bear to wait so long? How could he endure such an endless time and not go crazy with frustration?

The weather had eased long enough for Ulf and his companions to be away, and both Eirik and Hakon went with them. As if only waiting for their departure, the snow set in again, and Eyvind found his days full of digging, clearing paths to wood store and barn, endlessly shovelling the thick blanket from the thatch. Somerled followed him out, watching gravely as he swung up onto a barrel and clambered to the rooftop. From up there, the boy looked like a little shadow in the white.

"Go back inside!" Eyvind called down to him. "This is not a job for you!"

But Somerled began to climb up, slipped, cursed, climbed again; on tiptoes, balanced precariously on the barrel, he could just reach the eaves with his upstretched arms.

"You can't--" Eyvind began, looking over, and then stopped at the look in Somerled's eyes. He reached down and hauled the other boy up bodily by the arms. "Didn't bring a shovel, did you?" he observed mildly. "Watch me first, then you can take a turn. Next time bring your own; they're in the back near the stock pens. You need to keep moving or you'll freeze up and be no use to anyone."

He didn't expect Somerled to last long. It was bitterly cold, the shovel was large and heavy and the task backbreaking, even when you were as strong as Eyvind was. He worked a while, and then Somerled tried it, sliding about, losing his balance, teetering, and recovering. He managed to clear a small patch. His face grew white with cold, his eyes narrow and fierce.

"All right, my turn," Eyvind told him, finding it hard to stand idle when he knew he could do the job in half the time.

"I haven't d-done my share. I c-can go on."

"Rest first, then have another try," said Eyvind, taking the shovel out of Somerled's hands. "You'll get blisters. If I'm supposed to be teaching you, then you'd better learn to listen."

They did the job in turns. It took a while. He glanced at Somerled from time to time. The lad looked fit to drop, but something in his face suggested it would not be a good idea to tell him to go indoors and let Eyvind finish. So he endured Somerled's assistance, and at length the roof was cleared. When they went back inside, Ingi exclaimed over Somerled's chattering teeth, and his poor hands where lines of livid blisters were forming across the palms, and she chided Eyvind for pushing the boy so. Didn't he know Somerled was not used to such hard work? He should be easier on the lad. Eyvind muttered an apology, glancing sideways at his companion. Somerled shivered, and drank his broth, and said not a word. Maybe both of them were learning.

Several boys lived at Hammarsby. Some were the sons of housecarls, folk who had worked for Ingi so long they were almost family. Somerled did not exactly go out of his way to make friends, and in the confines of the snowbound longhouse it did not take long for others to notice this, and to set him small trials as befitted any newcomer. Someone slipped a dead rat between his blankets, to be discovered suddenly when he went weary to bed in the darkness. The next day, Eyvind spoke to the lads of the household, saying Somerled was not used to such pranks, having grown up without brothers or sisters, and that it was not to happen again. Nobody actually confessed. The morning after that, Ingi inquired what was wrong with the porridge, to make all the boys look so green in the face? Good food should never be wasted, especially in the cold season. But the only two eating were Eyvind and Somerled, and Somerled wore a little smile.

Later, Eyvind discovered the lads' gift had been returned to them in kind. Since there was no knowing who had planted the rat, Somerled had been scrupulously fair, and shared it among them in precisely cut portions. An ear and an eye. A nose with Whiskers. A length of gut. He had, it seemed, his very own way of solving problems.

Eyvind did not ask Somerled about his past. He did wonder, sometimes. There were so many things the boy did not know about, or just could not be. He had surely never looked after animals, for he seemed quite ignorant of how to treat them. He did not understand, until Eyvind explained it to him, that when a dog lowered its head and growled at you with flattened ears, you did not growl back or give it a kick. You must speak to it kindly, Eyvind told Somerled. You should not look it in the eye, just stay close and move slowly. You had to let the dog get used to you, and learn you could be trusted. Somerled had thought about this for a little, and then he had asked, "Why?" So, shaggy-coated Grip continued to growl and snap every time the boy went past, though the old dog let little children climb over his back and tug his rough coat with never a bark from him.

Somerled did not like snow games. Sometimes, when all their tasks were done to Ingi's satisfaction, the boys and girls of the household would venture out onto the hillside to hurtle down the slopes on wooden sleds or pieces or birch bark. There were clear, bright days when the world seemed made anew in winter shades of twig gray and snowdrift white under a sky as blue as a duck egg. Eyvind longed for the freedom of summer, but he loved this time as well. There was no feeling like speeding across the ice with the bone skates strapped to his boots, the sheer thrill of the air whipping by, the pounding of the heart, the fierce joy of pushing himself to the limit and knowing he was invincible. This was what it would be like when he became a Wolfskin and rode the prow of the longship: the same feeling, but a hundred times stronger.

He could not understand why Somerled would not join in these games. The other boys jeered at the newcomer and exchanged theories behind his back. Eyvind had tried to stop this, but he would not report it to Ingi; one did not tattle-tale. Besides, the boys were right. Somerled was a very odd child. What if he did fall off the sled, or land on his bottom on the ice? That had happened to all of them. People might laugh, but it would be a laughter of understanding, not of scorn. Yet Somerled would not even try. He stood in the darkness under the trees and watched them, stone-faced, and if anyone asked him why he did not join in, he would either ignore the question completely, or say he did not see any point in it.

Part of Eyvind wanted to forget that fierce-eyed small presence under the trees. Somerled made his own difficulties; let him deal with the consequences. Part of Eyvind wanted to skate away over the dark mirror of the frozen river, to join the others in wild races down the hillside, to build forts of snow or to venture out into the woods alone, spear in hand, seeking fresh meat for his mother's pot. But he'd promised Eirik. So, with decidedly mixed feelings, Eyvind devoted several lamplit evenings to fashioning a pair of skates from a piece of well-dried oak wood, iron-strong, with thongs of deerhide to fasten them to the boot soles. Somerled watched without comment.

Acting on an instinct he could not have explained, Eyvind got up very early, shrugging on his shirt and trousers, his tunic, his sheepskin coat and hat of felted wool as quickly as he could, for the cold seemed to seep into every corner of the longhouse. The place was quiet, the household still sleeping. He took his own skates and the new pair, and turned to wake Somerled. But, quiet as a shadow, the boy had risen from the wooden shelf where they slept, and was putting on his own clothes, as if he did not need to be told. It seemed Eyvind's instinct had served him well.

Ancient as he was, the dog Grip was ever keen to accompany the children on any expedition out of doors, as companion and protector. But today he seemed wary, growling softly as the two of them tiptoed into the hallway and out to the back door. Eyvind gave him a pat and pointed him back inside. Such an old dog was best resting by the embers of last night's fire, for the cold was enough to freeze the bollocks off you. He must be mad, taking Somerled out so early. Still, the boy followed willingly enough, asking not a single question.

Down by the frozen river, in a morning darkness where the snow seemed blue and the sky red, where bushes and trees stretched out twigs like skinny fingers, frost-silvered, into the strange winter light, Somerled strapped on the new skates with no hesitation at all, stood up, slipped on the ice, fell flat on his back, got up again and, arms gripped firmly by Eyvind's powerful hands, began to move forward step by sliding step. That was how simple it was. All that was needed was that nobody else should be there.

That astonished Eyvind. He himself was always first in any endeavor--not reckless exactly, just blithely confident of his own strength. He did get hurt from time to time, but thought little of it. It did not worry him if folk laughed at him, not that they often did, since he tended to get things right the first time. And he was bigger than other people, which did help. He understood danger and guarded against it; he used his skis and his bow and his axe in the right way, cleanly and capably. Somerled's need for privacy confused him. If others' opinions mattered so much, why should Somerled trust him? He was, after all, the brother of a Wolfskin. That might be expected to engender fear rather than trust in a scrap of a boy like this.

As time passed, it became apparent to Eyvind that Somerled was attempting a kind of repayment, in the limited ways available to him. Eyvind would fall into bed exhausted after a long day's work on the farm, and when he got up in the morning his boots would be cleaned of mud, dried, and waiting for him. Ingi would send her son out to the woodshed on a chill afternoon, and he would find Somerled there before him, frowning with effort as he loaded the logs onto the sledge. A choice cut of meat, served to their small visitor, would make its way unobtrusively to Eyvind's own platter. Eyvind learned quickly that one did not thank Somerled for these small kindnesses. Any attempt to do so would be greeted wither by a blank stare, or a furious denial that any favor was intended. So he learned merely to accept, and was rewarded, occasionally, with a tentative halfsmile, so fleeting he wondered, afterward, if he had only imagined it.

Winter slowly mellowed into spring, and Eyvind learned a lesson in patience. Before the ice melted, Somerled could skate; before the snow turned to slush he could move about on skis without falling. He did not play games, but it was apparent that this was through choice rather than lack of ability. The other boys' eyes were more wary than scornful now as they passed over his small, dark figure. He made no new friends.

The milder weather brought fresh pastimes. It was easier to teach Somerled things now, because spring was a time for expeditions, and Eyvind was accustomed to going alone. Now, wherever Eyvind led, Somerled followed, and there were no others to watch and make fun of the boy's errors. Accepting that this season's ventures must be shorter and their pace slower, Eyvind set about ensuring his companion understood the essential rules of safety, and the basic skills of hunting and trapping. Somerled learned to start a fire with no more than a scrap of flint and a handful of dry grass. He learned to build a shelter from fallen branches and strips of bark. He tried spear and bow and struggled with both, for he had little strength in the arms and shoulders, though his eye was keen. Eyvind set easy targets, and praised each small success. They set snares for rabbits and brought home a steady supply. Somerled had a neat hand for gutting and skinning.

Eyvind was uneasy sometimes. He could see Somerled was trying hard, and it was plain to all that the lad was growing stronger and healthier, thanks to fresh air and exercise and good feeding. But he remained very quiet, and had not lost his habit of blurting out strange remarks. Once, by the fire, they had listened to Igni's tale of three brothers going to seek their fortunes, and had spoken of what the future might hold for themselves, and what they aspired to. One lad was eager to be a craftsman; he hoped to persuade Bjarni the silversmith to take him on. Another wanted to voyage far away to the lands in the south, where all the folk had skin as black as night. A third dreamed of catching the biggest fish that ever slipped in through the skerry-guard.

"No need to ask Eyvind what he's going to do," grinned redheaded Sigurd, son of Igni's senior housecarl. "We all know that."

"If Thor accepts me, I'll be the bravest Wolfskin that ever gave service," Eyvind said quietly, his gaze intent on the hearth fire. "First in attack, heedless of peril, fierce and unassailable. That's the only thing I want to do."

There was a little silence. Not one of them doubted that this wish would come true. It seemed to have been understood among them since Eyvind was little more than a baby.

"I'm going to marry Ragna and have ten children," Sigurd joked, and pigtailed Ragna cuffed him, blushing scarlet.

"What about you, Somerled?" Igni asked kindly, perhaps feeling

their young visitor had been overlooked. "What do you think you will become, When are a man?"

Somerled looked up at her, his dark eyes opaque. "A king," he said.

There were snorts of ridicule. The boys rolled their eyes at one another; the girls giggled with embarrassment.

"I don't think you can just be a king," Eyvind said gently. "I; mean, a king is even more important than a Jarl. You'd have to be...well..." He hesitated. It was not possible to say, you'd have to be strong, brave respected--all the things Somerled was not.

"You doubt me?" Somereled snapped. His small face all at once had the appearance of a savage creature at by, the nostrils pinched, the eyes furious.

"Oh, come on, Somerled," said Sigurd. "You know you'll never be a king, that sort of thing' only in stories. It's a stupid thing to say."

Ingi opened her mouth, perhaps to announced that it was bedtime, but Somerled spoke first.

"A man can be anything he wants to be," he said, fixing Sigurd with a withering look. "You have still that lesson to learn But you will not learn it, because you set your sight too low. One day you'll be a bitter old man, looking back on a life wasted. Worse, you won't even have the wit to recognize what you might have been. One day I will be a king, and you will still be a housecarl."

Sigurd muttered something and made a gesture with his fingers. Then Ingi ordered them briskly off to bed, and the strange conversation was over.

Laying awake, Eyvind started up at the thatch, where small creatures stirred with furtive rustling movements. After a while he said, "I didn't mean it to sound like that. As if I thought you were lying. That wasn't What I mean. I was just trying to be..."

"Helpful?" put in Somerled.

"Well, yes. I through maybe you didn't understand how hard it would be to--to do what you said. Almost impossible, I should think."

Somerled sat up, his blankets help around him. "Nothing is impossible, Eyvind," he said in his small, precise voice. "Not if a man wants it enough. How badly do you wish to be a Wolfskin?"

"More than anything in the world," Eyvind said. "You know that; everyone does."

"Exactly," said Somerled. "So, you will be Wolfskin, because you cannot see a future in which that does not occur. It is the same for me. I don't expect to achieve what I want without hard work and careful strategy, of course."

Eyvind was silenced. Somerled sounded extremely sure; so sure there was no challenging him.

"You must not doubt me." There was an intensity in that statement that was almost frightening.

"I don't, Somerled," said Eyvind quietly and, to his own surprised, he found that he meant it.

Copyright © 2002 by Juliet Marillier

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details