Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: gallyangel

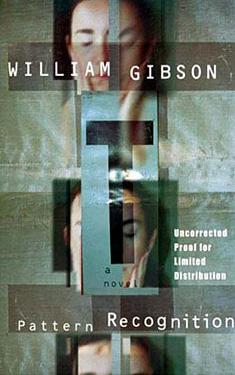

Pattern Recognition

| Author: | William Gibson |

| Publisher: |

G. P. Putnam's Sons, 2003 Viking UK, 2003 |

| Series: | The Blue Ant Trilogy: Book 1 |

|

1. Pattern Recognition |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Cyberpunk Near-Future Hard SF |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Cayce Pollard is an expensive, spookily intuitive market-research consultant. In London on a job, she is offered a secret assignment: to investigate some intriguing snippets of video that have been appearing on the Internet. An entire subculture of people is obsessed with these bits of footage, and anybody who can create that kind of brand loyalty would be a gold mine for Cayce's client. But when her borrowed apartment is burgled and her computer hacked, she realizes there's more to this project than she had expected.

Still, Cayce is her father's daughter, and the danger makes her stubborn. Win Pollard, ex-security expert, probably ex-CIA, took a taxi in the direction of the World Trade Center on September 11 one year ago, and is presumed dead. Win taught Cayce a bit about the way agents work. She is still numb at his loss, and, as much for him as for any other reason, she refuses to give up this newly weird job, which will take her to Tokyo and on to Russia. With help and betrayal from equally unlikely quarters, Cayce will follow the trail of the mysterious film to its source, and in the process will learn something about her father's life and death.

Excerpt

1.

THE WEBSITE OF DREADFUL NIGHT

Five hours' New York jet lag and Cayce Pollard wakes in Camden Town to the dire and ever-circling wolves of disrupted circadian rhythm.

It is that flat and spectral non-hour, awash in limbic tides, brainstem stirring fitfully, flashing inappropriate reptilian demands for sex, food, sedation, all of the above, and none really an option now.

Not even food, as Damien's new kitchen is as devoid of edible content as its designers' display windows in Camden High Street. Very handsome, the upper cabinets faced in canary-yellow laminate, the lower with lacquered, unstained apple-ply. Very clean and almost entirely empty, save for a carton containing two dry pucks of Weetabix and some loose packets of herbal tea. Nothing at all in the German fridge, so new that its interior smells only of cold and long-chain monomers.

She knows, now, absolutely, hearing the white noise that is London, that Damien's theory of jet lag is correct: that her mortal soul is leagues behind her, being reeled in on some ghostly umbilical down the vanished wake of the plane that brought her here, hundreds of thousands of feet above the Atlantic. Souls can't move that quickly, and are left behind, and must be awaited, upon arrival, like lost luggage.

She wonders if this gets gradually worse with age: the nameless hour deeper, more null, its affect at once stranger and less interesting?

Numb here in the semi-dark, in Damien's bedroom, beneath a silvery thing the color of oven mitts, probably never intended by its makers to actually be slept under. She'd been too tired to find a blanket. The sheets between her skin and the weight of this industrial coverlet are silky, some luxurious thread count, and they smell faintly of, she guesses, Damien. Not badly, though. Actually it's not unpleasant; any physical linkage to a fellow mammal seems a plus at this point.

Damien is a friend.

Their boy-girl Lego doesn't click, he would say.

Damien is thirty, Cayce two years older, but there is some carefully insulated module of immaturity in him, some shy and stubborn thing that frightened the money people. Both have been very good at what they've done, neither seeming to have the least idea of why.

Google Damien and you will find a director of music videos and commercials. Google Cayce and you will find "coolhunter," and if you look closely you may see it suggested that she is a "sensitive" of some kind, a dowser in the world of global marketing.

Though the truth, Damien would say, is closer to allergy, a morbid and sometimes violent reactivity to the semiotics of the marketplace.

Damien's in Russia now, avoiding renovation and claiming to be shooting a documentary. Whatever faintly lived-in feel the place now has, Cayce knows, is the work of a production assistant.

She rolls over, abandoning this pointless parody of sleep. Gropes for her clothes. A small boy's black Fruit Of The Loom T-shirt, thoroughly shrunken, a thin gray V-necked pullover purchased by the half-dozen from a supplier to New England prep schools, and a new and oversized pair of black 501's, every trademark carefully removed. Even the buttons on these have been ground flat, featureless, by a puzzled Korean locksmith, in the Village, a week ago.

The switch on Damien's Italian floor lamp feels alien: a different click, designed to hold back a different voltage, foreign British electricity.

Standing now, stepping into her jeans, she straightens, shivering.

Mirror-world. The plugs on appliances are huge, triple-pronged, for a species of current that only powers electric chairs, in America. Cars are reversed, left to right, inside; telephone handsets have a different weight, a different balance; the covers of paperbacks look like Australian money.

Pupils contracted painfully against sun-bright halogen, she squints into an actual mirror, canted against a gray wall, awaiting hanging, wherein she sees a black-legged, disjointed puppet, sleep-hair poking up like a toilet brush. She grimaces at it, thinking for some reason of a boyfriend who'd insisted on comparing her to Helmut Newton's nude portrait of Jane Birkin.

In the kitchen she runs tap water through a German filter, into an Italian electric kettle. Fiddles with switches, one on the kettle, one on the plug, one on the socket. Blankly surveys the canary expanse of laminated cabinetry while it boils. Bag of some imported Californian tea substitute in a large white mug. Pouring boiling water.

In the flat's main room, she finds that Damien's faithful Cube is on, but sleeping, the night-light glow of its static switches pulsing gently. Damien's ambivalence toward design showing here: He won't allow decorators through the door unless they basically agree to not do that which they do, yet he holds on to this Mac for the way you can turn it upside down and remove its innards with a magic little aluminum handle. Like the sex of one of the robot girls in his video, now that she thinks of it.

She seats herself in his high-backed workstation chair and clicks the transparent mouse. Stutter of infrared on the pale wood of the long trestle table. The browser comes up. She types Fetish:Footage:Forum, which Damien, determined to avoid contamination, will never bookmark.

The front page opens, familiar as a friend's living room. A frame-grab from #48 serves as backdrop, dim and almost monochrome, no characters in view. This is one of the sequences that generate comparisons with Tarkovsky. She only knows Tarkovsky from stills, really, though she did once fall asleep during a screening of The Stalker, going under on an endless pan, the camera aimed straight down, in close-up, at a puddle on a ruined mosaic floor. But she is not one of those who think that much will be gained by analysis of the maker's imagined influences. The cult of the footage is rife with subcults, claiming every possible influence. Truffaut, Peckinpah - The Peckinpah people, among the least likely, are still waiting for the guns to be drawn.

She enters the forum itself now, automatically scanning titles of the posts and names of posters in the newer threads, looking for friends, enemies, news. One thing is clear, though; no new footage has surfaced. Nothing since that beach pan, and she does not subscribe to the theory that it is Cannes in winter. French footageheads have been unable to match it, in spite of countless hours recording pans across approximately similar scenery.

She also sees that her friend Parkaboy is back in Chicago, home from an Amtrak vacation, California, but when she opens his post she sees that he's only saying hello, literally.

She clicks Respond, declares herself CayceP.

Hi Parkaboy. Nt

When she returns to the forum page, her post is there.

It is a way now, approximately, of being at home. The forum has become one of the most consistent places in her life, like a familiar café that exists somehow outside of geography and beyond time zones.

There are perhaps twenty regular posters on F:F:F, and some much larger and uncounted number of lurkers. And right now there are three people in Chat, but there's no way of knowing exactly who until you are in there, and the chat room she finds not so comforting. It's strange even with friends, like sitting in a pitch-dark cellar conversing with people at a distance of about fifteen feet. The hectic speed, and the brevity of the lines in the thread, plus the feeling that everyone is talking at once, at counter-purposes, deter her.

The Cube sighs softly and makes subliminal sounds with its drive, like a vintage sports car downshifting on a distant freeway. She tries a sip of tea substitute, but it's still too hot. A gray and indeterminate light is starting to suffuse the room in which she sits, revealing such Damieniana as has survived the recent remake.

Partially disassembled robots are propped against one wall, two of them, torsos and heads, like elfin, decidedly female crash-test dummies. These are effects units from one of Damien's videos, and she wonders, given her mood, why she finds them so comforting. Probably because they are genuinely beautiful, she decides. Optimistic expressions of the feminine. No sci-fi kitsch for Damien. Dreamlike things in the dawn half-light, their small breasts gleaming, white plastic shining faint as old marble. Personally fetishistic, though; she knows he'd had them molded from a body cast of his last girlfriend, minus two.

Hotmail downloads four messages, none of which she feels like opening. Her mother, three spam. The penis enlarger is still after her, twice, and Increase Your Breast Size Dramatically.

Deletes spam. Sips the tea substitute. Watches the gray light becoming more like day.

Eventually she goes into Damien's newly renovated bathroom. Feels she could shower down in it prior to visiting a sterile NASA probe, or step out of some Chernobyl scenario to have her lead suit removed by rubber-gowned Soviet technicians, who'd then scrub her with long-handled brushes. The fixtures in the shower can be adjusted with elbows, preserving the sterility of scrubbed hands.

She pulls off her sweater and T-shirt and, using hands, not elbows, starts the shower and adjusts the temperature.

FOUR hours later she's on a reformer in a Pilates studio in an upscale alley called Neal's Yard, the car and driver from Blue Ant waiting out on whatever street it is. The reformer is a very long, very low, vaguely ominous and Weimar-looking piece of spring-loaded furniture. On which she now reclines, doing v-position against the foot rail at the end. The padded platform she rests on wheels back and forth along tracks of angle-iron within the frame, springs twanging softly. Ten of these, ten toes, ten from the heels. In New York she does this at a fitness center frequented by dance professionals, but here in Neal's Yard, this morning, she seems to be the sole client. The place is only recently opened, apparently, and perhaps this sort of thing is not yet so popular here. There is that mirror-world ingestion of archaic substances, she thinks: People smoke, and drink as though it were good for you, and seem to still be in some sort of honeymoon phase with cocaine. Heroin, she's read, is cheaper here than it's ever been, the market still glutted by the initial dumping of Afghani opium supplies.

Done with her toes, she changes to heels, craning her neck to be certain her feet are correctly aligned. She likes Pilates because it isn't, in the way she thinks of yoga, meditative. You have to keep your eyes open, here, and pay attention.

That concentration counters the anxiety she feels now, the pre-job jitters she hasn't experienced in a while.

She's here on Blue Ant's ticket. Relatively tiny in terms of permanent staff, globally distributed, more post-geographic than multinational, the agency has from the beginning billed itself as a high-speed, low-drag life-form in an advertising ecology of lumbering herbivores. Or perhaps as some non-carbon-based life-form, entirely sprung from the smooth and ironic brow of its founder, Hubertus Bigend, a nominal Belgian who looks like Tom Cruise on a diet of virgins' blood and truffled chocolates.

The only thing Cayce enjoys about Bigend is that he seems to have no sense at all that his name might seem ridiculous to anyone, ever. Otherwise, she would find him even more unbearable than she already does.

It's entirely personal, though at one remove.

Still doing heels, she checks her watch, a Korean clone of an old-school Casio G-Shock, its plastic case sanded free of logos with a scrap of Japanese micro-abrasive. She is due in Blue Ant's Soho offices in fifty minutes.

She drapes a pair of limp green foam pads over the foot rail, carefully positions her feet, lifts them on invisible stiletto heels, and begins her ten prehensile.

2.

BITCH

CPUs for the meeting, reflected in the window of a Soho specialist in mod paraphernalia, are a fresh Fruit T-shirt, her black Buzz Rickson's MA-1, anonymous black skirt from a Tulsa thrift, the black leggings she'd worn for Pilates, black Harajuku schoolgirl shoes. Her purse-analog is an envelope of black East German laminate, purchased on eBay-if not actual Stasi-issue then well in the ballpark.

She sees her own gray eyes, pale in the glass, and beyond them Ben Sherman shirts and fishtail parkas, cufflinks in the form of the RAF roundel that marked the wings of Spitfires.

CPUs. Cayce Pollard Units. That's what Damien calls the clothing she wears. CPUs are either black, white, or gray, and ideally seem to have come into this world without human intervention.

What people take for relentless minimalism is a side effect of too much exposure to the reactor-cores of fashion. This has resulted in a remorseless paring-down of what she can and will wear. She is, literally, allergic to fashion. She can only tolerate things that could have been worn, to a general lack of comment, during any year between 1945 and 2000. She's a design-free zone, a one-woman school of anti whose very austerity periodically threatens to spawn its own cult.

Around her the bustle of Soho, a Friday morning building toward boozy lunches and careful chatter in all these restaurants. To one of which, Charlie Don't Surf, she will be going for an obligatory post-meeting meal. But she feels herself tipping back down into a miles-long trough of jet lag, and knows that that is what she must surf now: her lack of serotonin, the delayed arrival of her soul.

She checks her watch and heads down the street, toward Blue Ant, whose premises until recently were those of an older, more linear sort of agency.

The sky is a bright gray bowl, crossed with raveled contrails, and as she presses the button to announce herself at Blue Ant, she wishes she'd brought her sunglasses.

SEATED now, opposite Bernard Stonestreet, familiar from Blue Ant's New York operation, she finds him pale and freckled as ever, with carroty hair upswept in a weird Aubrey Beardsley flame motif that might be the result of his having slept on it that way, but is more likely the work of some exclusive barber. He is wearing what Cayce takes to be a Paul Smith suit, more specifically the 118 jacket and the 11T trouser, cut from something black. In London his look seems to be about wearing many thousand pounds' worth of garments that appear to have never been worn before having been slept in, the night before. In New York he prefers to look as though he's just been detailed by a tight scrum of specialists. Different cultural parameters.

On his left sits Dorotea Benedetti, her hair scraped back from her forehead with a haute nerd intensity that Cayce suspects means business and trouble both. Dorotea, whom Cayce knows glancingly from previous and minor business in New York, is something fairly high up in the graphics design partnership of Heinzi & Pfaff. She has flown in, this morning, from Frankfurt, to present H&P's initial shot at a new logo for one of the world's two largest manufacturers of athletic footwear. Bigend has defined a need for this maker to re-identify, in some profound but so far unspecified way. Sales of athletic shoes, "trainers" in the mirror-world, are tanking bigtime, and the skate shoes that had already started to push them under aren't doing too well either. Cayce herself has been tracking the street-level emergence of what she thinks of as "urban survival" footwear, and though this is so far at the level of consumer re-purposing, she has no doubt that commodification will soon follow identification.

The new logo will be this firm's pivot into the new century, and Cayce, with her marketable allergy, has been brought over to do in person the thing that she does best. That seems odd to her, or if not odd, archaic. Why not teleconference? There may be so much at stake, she supposes, that security is an issue, but it's been a while now since business has required her to leave New York.

Whatever, Dorotea's looking serious about it. Serious as cancer. On the table in front of her, perhaps a millimeter too carefully aligned, is an elegant gray cardboard envelope, fifteen inches on a side, bearing the austere yet whimsical logo of Heinzi & Pfaff. It is closed with one of those expensively archaic fasteners consisting of a length of cord and two small brown cardboard buttons.

Cayce looks away from Dorotea and the envelope, noting that a great many Nineties pounds had once been lavished on this third-floor meeting room, with its convexly curving walls of wood suggesting the first-class lounge of a transatlantic zeppelin. She notices threaded anchors exposed on the pale veneer of the convex wall, where once had been displayed the logo of whichever agency previously occupied the place, and early warning signs of Blue Ant renovation are visible as well: scaffolding erected in a hallway, where someone has been examining ductwork, and rolls of new carpeting stacked like plastic-wrapped logs from a polyester forest.

Dorotea may have attempted to out-minimalize her this morning, Cayce decides. If so, it hasn't worked. Dorotea's black dress, for all its apparent simplicity, is still trying to say several things at once, probably in at least three languages. Cayce has hung her Buzz Rickson's over the back of her chair, and now she catches Dorotea looking at it.

The Rickson's is a fanatical museum-grade replica of a U.S. MA-1 flying jacket, as purely functional and iconic a garment as the previous century produced. Dorotea's slow burn is being accelerated, Cayce suspects, by her perception that Cayce's MA-1 trumps any attempt at minimalism, the Rickson's having been created by Japanese obsessives driven by passions having nothing at all to do with anything remotely like fashion.

Cayce knows, for instance, that the characteristically wrinkled seams down either arm were originally the result of sewing with pre-war industrial machines that rebelled against the slippery new material, nylon. The makers of the Rickson's have exaggerated this, but only very slightly, and done a hundred other things, tiny things, as well, so that their product has become, in some very Japanese way, the result of an act of worship. It is an imitation more real somehow than that which it emulates. It is easily the most expensive garment Cayce owns, and would be virtually impossible to replace.

"You don't mind?" Stonestreet producing a pack of cigarettes called Silk Cut, which Cayce, never a smoker, thinks of as somehow being the British equivalent of the Japanese Mild Seven. Two default brands of creatives.

"No," says Cayce. "Please do."

There is actually an ashtray on the table, a small one, round and perfectly white. As archaic a fixture in America, in the context of a business meeting, as would be one of those flat and filigreed absinthe trowels. (But in London, she knew, you might encounter those as well, though she'd not yet seen one at a meeting.) "Dorotea?" Offering the pack, but not to Cayce. Dorotea declining. Stonestreet puts a filter tip between his tidily mobile lips and takes out a box of matches that Cayce assumes were acquired in some restaurant the night before. The matchbox looks very nearly as expensive as Dorotea's gray envelope. He lights up. "Sorry we had to haul you over for this, Cayce," he says. The spent match makes a tiny ceramic sound when he drops it into the ashtray.

"It's what I do, Bernard," Cayce says.

"You look tired," says Dorotea.

"Four hours difference." Smiling with only the corners of her mouth.

"Have you tried those pills from New Zealand?" Stonestreet asks. Cayce remembers that his American wife, once the ingénue in a short-lived X-Files clone, is the creator of an apparently successful line of vaguely homeopathic beauty products.

"Jacques Cousteau said that jet lag was his favorite drug."

"Well?" Dorotea looks pointedly at the H&P envelope.

Stonestreet blows a stream of smoke. "Well yes, I suppose we should."

They both look at Cayce. Cayce looks Dorotea in the eye. "Ready when you are."

Dorotea unwinds the cord from beneath the cardboard button nearest Cayce. Lifts the flap. Reaches in with thumb and forefinger.

There is a silence.

"Well then," Stonestreet says, and stubs out his Silk Cut.

Dorotea removes an eleven-inch square of art board from the envelope. Holding it at the upper corners, between the tips of perfectly manicured forefingers, she displays it to Cayce.

There is a drawing there, a sort of scribble in thick black Japanese brush, a medium she knows to be the in-house hallmark of Herr Heinzi himself. To Cayce, it most resembles a syncopated sperm, as rendered by the American underground cartoonist Rick Griffin, circa 1967. She knows immediately that it does not, by the opaque standards of her inner radar, work. She has no way of knowing how she knows.

Briefly, though, she imagines the countless Asian workers who might, should she say yes, spend years of their lives applying versions of this symbol to an endless and unyielding flood of footwear. What would it mean to them, this bouncing sperm? Would it work its way into their dreams, eventually? Would their children chalk it in doorways before they knew its meaning as a trademark?

"No," she says.

Stonestreet sighs. Not a deep sigh. Dorotea returns the drawing to its envelope but doesn't bother to reseal it.

Cayce's contract for a consultation of this sort specifies that she absolutely not be asked to critique anything, or provide creative input of any sort. She is only there to serve as a very specialized piece of human litmus paper.

Dorotea takes one of Stonestreet's cigarettes and lights it, dropping the wooden match on the table beside the ashtray. "How was the winter, then, in New York?"

"Cold," Cayce says.

"And sad? It is still sad?"

Cayce says nothing.

"You are available to stay here," Dorotea asks, "while we go back to the drawing board?"

Cayce wonders if Dorotea knows the cliché. "I'm here for two weeks," she says. "Flat-sitting for a friend."

"A vacation, then."

"Not if I'm working on this."

Dorotea says nothing.

"It must be difficult," Stonestreet says, between steepled, freckled fingers, his red thatch rising above them like flames from a burning cathedral, "when you don't like something. Emotionally, I mean."

Cayce watches Dorotea rise and, carrying her Silk Cut, cross to a sideboard, where she pours Perrier into a tumbler.

"It isn't about liking anything, Bernard," Cayce says, turning back to Stonestreet, "it's like that roll of carpet, there; it's either blue or it's not. Whether or not it's blue isn't something I have an emotional investment in."

She feels bad energy brush past her as Dorotea returns to her seat.

Dorotea puts her water down beside the H&P envelope and does a rather inexpert job of stubbing out her cigarette. "I will speak with Heinzi this afternoon. I would call him now but I know that he is in Stockholm, meeting with Volvo."

The air seems very thick with smoke now and Cayce feels like coughing.

"There's no rush, Dorotea," Stonestreet says, and Cayce hopes that this means that there really, really is.

CHARLIE Don't Surf is full, the food California-inflected Vietnamese fusion with more than the usual leavening of colonial Frenchness. The white walls are decorated with enormous prints of close-up black-and-white photographs of 'Nam-era Zippo lighters, engraved with crudely drawn American military symbols, still cruder sexual motifs, and stenciled slogans. These remind Cayce of photographs of tombstones in Confederate graveyards, except for the graphic content and the nature of the slogans, and the 'Nam theme suggests to her that the place has been here for a while.

IF I HAD A FARM IN HELL AND A HOUSE IN VIETNAM I'D SELL THEM BOTH

The lighters in the photographs are so worn, so dented and sweat-corroded, that Cayce may well be the first diner to ever have deciphered these actual texts.

BURY ME FACE DOWN SO THE WORLD CAN KISS MY ASS

"His surname actually is 'Heinzi,' you know," Stonestreet is saying, pouring a second glass of the Californian cabernet that Cayce, though she knows better, is drinking. "It only sounds like a nickname. Any given names, though, have long since gone south."

"Ibiza," Cayce suggests.

"Er?"

"Sorry, Bernard, I'm tired."

"Those pills. From New Zealand."

THERE IS NO GRAVITY THE WORLD SUCKS

"I'll be fine." A sip of wine.

"She's a piece of work, isn't she?"

"Dorotea?"

Stonestreet rolls his eyes, which are a peculiar brown, inflected as with Mercurochrome; something iridescent, greenly copper-tinged.

173 AIRBORNE

She asks after the American wife. Stonestreet dutifully recounts the launch of a cucumber-based mask, the thin end of a fresh wedge of product, touching on the politics involved in retail placement. Lunch arrives. Cayce concentrates on tiny fried spring rolls, setting herself for auto-nod and periodically but sympathetically raised eyebrows, grateful that he's carrying the conversational ball. She's way down deep in that trough now, with the half-glass of cabernet starting to exert its own lateral influence, and she knows that her best course here is to make nice, get some food in her stomach, and be gone.

But the Zippo tombstones, with their existential elegies, tug at her.

PHU CAT

Restaurant art that diners actually notice is a dubious idea, particularly to one with Cayce's peculiar, visceral, but still somewhat undefined sensitivities.

"So when it looked as though Harvey Knickers weren't going to come aboard."

Nod, raise eyebrows, chew spring roll. This is working. She covers her glass when he starts to pour her more wine.

And so she makes it easily enough through lunch with Bernard Stonestreet, blipped occasionally by these emblematic place-names from the Zippo graveyard (CU CHI, QUI NHON ) lining the walls, and at last he has paid and they are standing up to leave.

Reaching for her Rickson's, where she'd hung it on the back of her chair, she sees a round, freshly made hole, left shoulder, rear, the size of the lit tip of a cigarette. Its edges are minutely beaded, brown, with melted nylon. Through this is visible a gray interlining, no doubt to some particular Cold War mil-spec pored over by the jacket's otaku makers.

"Is something wrong?"

"No," Cayce says, "nothing." Putting on her ruined Rickson's.

Near the door, on their way out, she numbly registers a shallow Lucite cabinet displaying an array of those actual Vietnam Zippos, perhaps a dozen of them, and automatically leans closer.

SHIT ON MY DICK OR BLOOD ON MY BLADE

Which is very much her attitude toward Dorotea, right now, though she doubts she'll be able to do anything about it, and will only turn the anger against herself.

Copyright © 2003 by William Gibson

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details