Added By: illegible_scribble

Last Updated: Administrator

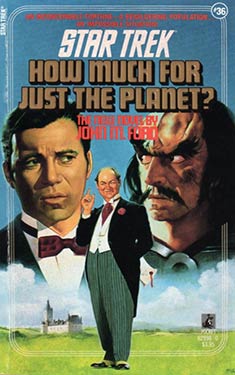

How Much for Just the Planet?

Synopsis

Dilithium: in crystalline form, the most valuable mineral in the galaxy. It powers the Federation's starships... and the Klingon Empire's battlecruisers. Now on a small, out-of-the-way planet named Direidi, the greatest fortune in dilithium crystals ever seen has been found.

Under the terms of the Organian Peace Treaty, the planet will go to the side best able to develop the planet and its resources. Each side will contest the prize with the prime of its fleet: for the Federation -- Captain James T. Kirk and the Starship Enterprise; for the Klingons -- Captain Kaden vestai-Oparai and the Fire Blossom.

Except the Direidians are writing their own script for this contest -- a script that propels the crew of the Starship Enterprise into their strangest adventure yet.

Excerpt

Chapter One: In Space No One Can Fry an Egg

The officers' mess of the starship USS Enterprise was a small, rather cozy room, with comfortable chairs, moderately bright lighting, and a food-service wall with four delivery slots, no waiting. This morning, two officers entered the room, dropped briefing folders marked Top Secret onto the table, and approached the service wall.

"I don't know, Scotty," said Captain James T. Kirk, with an offhand gesture toward the secret documents. "Maybe it's just the idea of an inflatable rubber starship that bothers me." Kirk turned to face the messroom wall. "Two eggs, sunny side up," he told it, "bacon crisp, wheat toast, and a large orange juice." The wall went pleep in acknowledgment.

"Oatcakes wi' butter an' syrup," Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott told the wall, "a broiled kipper, an' coffee black." Pleep. "Rubber's hardly the word for the material, Captain. It's a triple-monolayer sandwich: an organic polymer inside to keep th' gas in, metal film on the outside to reflect sensors like real ship's hull, an' a pseudofluid sealant between 'em."

Ploop went the wall. "I do not have that sandwich on today's menu," it said, in a pleasantly maternal voice. "May I suggest the grilled cheese with Canadian bacon?"

Scott gave the wall an amiable kick. "An' each of the prototypes is nae bigger than a desk while it's collapsed, includin' the inflation system. Not that it takes much gas to fill her out, not in hard vacuum; a couple o' lungfuls --"

"Mr. Scott somewhat underestimates the volume of gas required," said a voice from the messroom doorway. "The inflation system holds twenty-seven cubic meters of compressed dry nitrogen. Exhaled breath of course contains moisture and respiratory waste products, which would be quite damaging to the material of the Deployable Practice Target."

"Good morning, Spock," Kirk said patiently.

Science Officer Spock entered the mess, hands folded and eyebrows arched. "It does seem the start of a productive day," he said, as the door hissed shut behind him. "One hundred grams of unsalted soya wafers, with one hundred twenty grams of defatted cream cheese," Spock told the wall, "and two hundred milliliters of unsweetened grapefruit juice." Pleep.

"I admit that the Deployable Target is a very fancy rubber balloon," Kirk said, "not to mention expensive -- "

"Two point eight six three million credits for each of the four prototypes," Spock said.

" -- but it's still shooting rubber fish in a barrel."

Ploop. "Fried fish are available -- "

Kirk ignored the wall and looked past the steep rise of Spock's eyebrow. "Balloons can't maneuver tactically, and yes, I've read the stuff in the Starfleet Institute Proceedings about 'pretending three-hundred-meter starships are Sopwith Camels.'"

Pling went the wall, and a panel slid open to reveal a tray. Two eggs looked sunny side up from the plate above a smile of bacon. Kirk took the tray to the dining table.

The door opened again, and Ship's Surgeon Leonard McCoy came in. Without a word to anyone, he walked crookedly to the wall, leaned heavily against it, and said something that sounded like "Plergb hfarizz ungemby, and coffee."

Bones McCoy was not a morning person.

Pleep, the wall replied, and then pling for the delivery of Scott's breakfast, and pling again for Spock's. They sat down at the table with Kirk.

The captain had broken the yolk on one of his eggs, buttered his toast, and had his glass two-thirds of the way to his mouth before noticing that the liquid in the tumbler was blue.

Not the deep indigo of grape juice, or the soothing azure of Romulan ale, but a luminous, electric blue, a color impossible in nature.

Kirk looked around the table. Scott and Spock were discussing some obscure engineering aspect of the bal -- Deployable Practice Target. There didn't seem to be anything wrong with their breakfasts; Scott's black coffee was black, Spock's juice was pale gold. Dr. McCoy was still waiting for his meal, watching the rest of them like a vulture with a hangover, but his stare had a distinctly unfocused quality. Maybe it was just the early hour, Kirk thought, a trick of the light or something. He looked at his juice again. Still blue.

Starship captains are a special breed of beings who boldly go, et cetera. Kirk took a sip of the blue liquid. It tasted just like orange juice. It even had pulp that got caught in his teeth, just like orange juice.

One more look. Blue.

The wall plinged, and McCoy brought his tray to the table. Kirk looked at the doctor's meal: there was a huge mug of coffee, a slab of Virginia ham, and an enormous heap of something else. The something else was orange, in the same way Kirk's juice had not been orange: it was signal-flare orange, bright as a Christmas necktie. Kirk noticed that Spock and Scotty had stopped talking, and eating, and were looking intently at the orange mound on the doctor's plate.

Oblivious, McCoy buttered the orange heap, sliced the ham, and went at them like a starving man.

After a moment, Spock finished his crackers and cheese, stood up, and slipped his tray into the disposal slot. "Excuse me, Captain, Mr. Scott, Dr. McCoy. I have some preparations to make for the Target tests."

"Aye," Scott said, watching McCoy eat as the syrup congealed around his own oatcakes. Kirk said "Of course, Spock." McCoy said "Gmltfrbl."

Spock looked sidelong at McCoy's plate, turned sharply and went out. Kirk thought he looked rather green, even for a Vulcan.

"I'd better check over the launch tubes," Scott said. "For, uh, th' tests, an' all." He went out.

Kirk watched, fascinated, as Dr. McCoy forked down the orange stuff, interspersed with chunks of ham and gulps of coffee. Finally McCoy drank deep from his mug, sat back in his chair, and let out a long sigh and a short burp.

He looked at Kirk, and frowned. "What's the matter, Jim? Haven't y'ever seen a man eat grits before?"

"I, um..."

"And what in the name of Hygeia are you drinking?"

"Morning, ah, pick-me-up," Kirk said hastily, and emptied the glass to the last blue drop. "'Scuse me, Bones, lots to do today." He stood up and dumped his tray, with one uneaten egg still on it. There was no waste; the food processors would recycle it, Kirk thought, and at once regretted thinking.

It was, the captain thought as he left the puzzled doctor in the messroom, going to be one of those days.

Not far away, silent in silent deep space, Federation resource exploratory vessel Jefferson Randolph Smith cruised at Warp Factor Four, her sensor net spread wide in search of dilithium. Dilithium, that rare and refractory mineral that powers the warp drive, indeed the Federation itself...but more about dilithium a little later. Just now, aboard Smith, the captain was also having one of those days.

But then, thought Captain Tatyana Trofimov, as she sipped her blue orange juice, it always seemed to be one of those days.

The rest of Smith's officers were at the messroom table with Captain Trofimov. The first officer, a Withiki named Tellihu, had his broad, red-feathered wings draped over the back of his chair, he read a freshly printed newsfax with his left hand and ate a mushroom omelet with his right. Tellihu had had eggs for breakfast every morning of Smith's mission, four hundred and sixty-six days so far, and it still seemed to Captain Trofimov vaguely like cannibalism.

Science Officer T'Vau had finished her soya salad and was looking at a chess set. Not playing with it, not touching the pieces, just looking. T'Vau's hair was dangling over one pointed ear, and there were vinegar-and-oil spots on her uniform blouse. For a Vulcan, the Captain thought, T'Vau was really a slob.

The three of them were all the officers aboard Jefferson Randolph Smith, and also all the crew, just as this compartment was not only the messroom but the common room and the recreation room. Smith (NCC-29402, Sulek-class) was a ship of the Resources Division, Exploration Command, designed to seek out -- no, not what you're thinking -- seek out minerals, especially dilithium, at the lowest possible cost.

It was actually not such a small ship, really quite roomy given its crew of three. And Starfleet Psychological Division had been very aware that a crew of only three for a mission of twenty to twenty-eight months must be carefully chosen for compatibility. PsyComm recommended that a special battery of crew-relations tests be designed.

The test designers were hard at work and expected to deliver a preliminary report no later than six months from now. Until then -- well, somebody had to bring in the dilithium.

Captain Trofimov came from Reynaud II, a thinly populated planet on the Cygnus-Carina Fringe, without much space trade. Trofimov had decided very young that she was not only going to enlist in Starfleet and get off Reynaud II, she was going to get every millimeter as far off Reynaud II as Starfleet went. Exploration Command seemed like just the thing. The recruiter showed her trishots of the big mining ships, like Dawson City, and the planetformers, like Robert Moses, vessels bigger than starships, bigger than starbases, and Trofimov knew that her destiny was sealed.

Only too right, she thought.

Tellihu finished his omelet, stood up, and said something to the wall in the whistling Withiki language. Pleep, the wall said, then pling. Tellihu took out what looked to Trofimov like an ice cream cone filled with birdseed and went out of the room nibbling it, dipping his wings to clear the doorway.

He does it deliberately, the captain thought. He'd eat worms if he thought he could get away with it.

She looked at T'Vau. The science officer picked a kelp strand out of her salad bowl and chewed on it idly, still watching the chess set. Finally she reached out, picked up a pawn, turned it over in her fingers, then put it back on its original square.

Trofimov finished her juice without looking at it, and left T'Vau to her, uh, game. As she went into the corridor she thought, I'll bet it's never like this for starship captains....

Not much farther away at all, the Imperial Klingon cruiser Fire Blossom patrolled the Organian Treaty Zone that separated the Empire from the Federation.

Fire Blossom was named for an incident in the youth of its captain, Kaden vestai-Oparai. Kaden had been an ensign, helmsman aboard a B-5 destroyer in one of the Wars of Internal Dissension. A lucky hit had pierced the destroyer's screens and killed most of the bridge crew, including the captain. Kaden had seized command, only to realize that he had a small and damaged ship being hotly pursued by a light attack cruiser.

Kaden broke formation and made for the nearest sun, dodging the cruiser's fire. The deflectors began shining with energy, the hull to heat despite them. The pursuer closed in. There was no practical chance of survival: the cruiser's heavier screens could sustain a much closer approach to the star, almost to the photosphere. It didn't even have to fire weapons. Just a little more pursuit, and Kaden's ship would melt.

At the last possible moment before the B-5 flashed to vapor, Kaden ejected a survival pod on maximum drive and broke away at nearly ninety degrees, calculating that the cruiser's captain would swing behind him, looking suddenly from intolerable light into darkness, and take a moment to line up his final shot. He would pay no attention to the pod; it was doomed to vaporize in an instant.

Kaden's guess was right. And as the cruiser took aim, the pod Kaden had jettisoned struck the star. Its contents, four magnetic bottles of antimatter, collapsed, and even antiplasma reacts violently with normal matter. There was an eruption from the solar surface, a very small prominence by solar standards, but big enough to engulf the cruiser. The light of its shields collapsing was lost in the sun.

That had been many years ago, Kaden thought as he ordered breakfast from the messroom wall. That had been when life was really enjoyable. Now he commanded a D-7c, a heavy-enhanced battlecruiser as much more powerful than that little destroyer as the destroyer outgunned its survival pod. There was not a deck officer in the entire Imperial Klingon Navy who would not have been excited to command a D-7c into battle against any foe of the Empire.

Unfortunately, ever since the business with the Organians, there had been a real shortage of foes of the Empire you could go into battle against. Try anything the least bit violent in one of the Treaty Zones, and everything like a weapon on the ship, from main-battery controls to cutlery, got red-hot, and some disembodied voice lectured you on the Treaty provisions.

Kaden had seen it happen, as an ensign. His squadron had run across a couple of Tellarite freighters, no armament, no escorts, nothing, they were practically towing a sign saying PLEASE HIJACK And practically before the cruisers were in attack formation -- hiss, thunder, you could have fried chops on the Weapons Control board. One of Kaden's bunkmates had been in the portside ratings' head; the Organian lightbulbs, had a pretty strange idea of what constituted a weapon. Then, Organians were some kind of pure energy. They probably didn't need disposal cubicles.

At any rate, thanks to the busybody lightbulbs, Kaden's command was about as thrilling as watching yeast grow. And speaking of yeast...Kaden looked down at his battertoast, hot and crisp from the wall unit. He shook his head. He looked at his glass of sweetened fruit juice: it seemed all right. He took a long gulp. The rapid Klingon metabolism broke simple sugars down almost instantly, producing a thoroughly pleasant buzz. Just the thing to get started in the morning.

There were consolations, Kaden thought. For one thing, his bridge crew did include Arizhel.

Rish came into the messroom precisely then. Kaden just about jumped at the coincidence, then settled back to watch her. She punched buttons on the meal console, then leaned against the wall. Admirable hull design, Kaden thought, splendid computing equipment. And very sophisticated defensive systems, too, which had thus far precluded any direct sensor analysis, never mind tractors and boarding.

Oh, well, Kaden thought, maybe in the Black Fleet...He had a sudden, more immediate thought. "Don't dial up the battertoast."

"What's wrong with the battertoast?" Rish said, as the console bell rang and the tray slid from the slot. She looked down. "Gday't!"

"Well, not literally," Kaden said, and picked up one of the green-coated sticks of toast from his own tray. "They taste all right, if you don't look at them."

Chief Engineer Askade, rather tall and slender for an Imperial-race Klingon, and Security Officer Maglus, built like a stormwalker and just as dangerous, came into the messroom and punched for meals.

Arizhel said, "What do you make of this, Chief Engineer?" She held up one of the green sticks.

Askade took the battertoast, looked at it blearily. "I can't rewire it into a death ray without some extra parts," he said, and took a bite. "Hm. Tastes okay. What's the problem?"

"The color, that's what the problem is."

"Oh?" Askade held the stick close to his eyes, tried to focus on it. "Oh. Hm."

Maglus took his tray from the machine. There was a slab of rare steak and four fried eggs on it, and a liter mug of juice. The eggs had blue yolks. Maglus looked at them for a moment, then shrugged and doused them with hot sauce. He began eating heartily.

Kaden said, "Maybe a couple of feed pipes got crossed, and it's recycling the used laundry instead. This is a sort of undress-tunic green, isn't it?"

"That's most unlikely," Askade said, in an unconvincing tone.

"When I think of what the food synths are supposed to be recycling," Maglus put in between bites, "I'm not sure that old socks would be so much worse."

The intercom whistled, and the voice of Communications Officer Aperokei came on. "Captain Kaden, Commander Arizhel, wanted on the bridge." Aperokei's voice was, as ever, bright and eager enough to put ice in one's blood.

Rish touched the com key. "What is it, Proke?"

"Ship on sensors, Commander. Looks like a Federation vessel."

"Can you identify?" Kaden said.

"It's small, Captain. Not likely to be a warship. She's sublight, in the shallows."

There was a pause. Somewhere or another Aperokei had acquired a fondness for Federation films, and it showed up in his language. "She's what, Lieutenant?" Kaden said patiently.

"Cislunar orbit, I mean, Captain."

Arizhel said, "Sounds like a mapper or surveyor."

"I suppose we should take a look," Kaden said, feeling uneasy already. "Pay our respects, smile at them."

"Carefully," Maglus said.

Askade was idly turning his fork over in his hands. "All we need this morning is a visit from the Org -- " He put the fork down, pushed it away.

"We're coming, Proke," Arizhel told the intercom.

"Aye, Commander. We'll look sharp from the bow."

The officers looked at each other, with expressions from bemused to grim. "That youth was raised wrong," Askade said, and they dumped their trays and headed for the bridge.

Aboard Jefferson Randolph Smith, Captain Trofimov settled into her swivel chair at the center of the bridge. It wasn't a very big bridge, only a room four meters square, and the chair squeaked and its upholstery was patched with plastic tape, but it was Trofimov's bridge, and chair, and command. Content, she switched on the main forward display.

It showed a roomful of people staring at three-dimensional chess sets.

"Computer," Trofimov said, cautiously. A few months back, T'Vau had spilled a milkshake into the computer's main logic bank, and it hadn't been quite the same since.

"Proud to be active and functional, Captain," the computer said.

"Computer, what is on the main display?"

"This is the 68th All-Federation Trimenchess Championship, Captain."

"I see. Why is it on the screen? Did the science officer request it?"

"No, Captain. I simply thought that Lieutenant Commander T'Vau might find it of interest. Considering her interest in the game. And so forth."

"Very well. But please clear -- " Trofimov stopped. The chess players on the screen were all sitting alone at sets; not one had an opponent visible. She mentioned this to the computer.

"That is correct, Captain. All these players are competing against the J-9bis duotronic polyprocessor computer known as Polymorphy. They are all predicted to resign in twenty moves or less."

"Why...I mean, enhance, Computer."

"I am sorry, Captain, but even though as a 1-2 duotronic unit I am directly related to the J-9bis, I lack the capacity to analyze why all these Vulcans might want to play this pointless game."

"I see. And you thought that the science officer might find it... interesting."

"I do my best to anticipate and fulfill the needs of my crew, Captain. Excuse me, your crew."

"Thank you, Computer. Clear the screen, please. Forward camera view."

The screen blanked and the normal starfield appeared.

Trofimov wondered about the computer. T'Vau swore the milkshake hadn't done any real damage. Could computers go stir-crazy like people? Troftmov didn't know. They hadn't had talking computers on Reynaud II. There was a law against it. When she went offworld, Trofimov thought that the law was a typically stupid, backwater, Reynaud II notion. She wasn't so sure anymore.

The milkshake had been some strange Vulcan flavor that smelled like peppermint. There had been a lot of sparks and a really awful smell, like roasted cottage cheese, for weeks. Still, T'Vau knew computers.

"Captain Trofimov?"

"Yes, Computer?"

"We're alone, aren't we? I mean, the science officer isn't on the bridge, is she?"

"No, Computer...Your sensors aren't malfunctioning, are they?" As she considered the possibility, it didn't seem as terrible. If the sensors weren't working, they couldn't find dilithium. If they couldn't find dilithium, there was no point in their being out here. They could go home.

"My sensors are fine, Captain. In fact, my sensors are really great. I can't imagine why you might think there's anything wrong with my sensors, they're just in tip-top shape."

"You asked if T'Vau was on the bridge."

"Oh. Well. I thought she might be...hiding."'

"Hiding?"

"Yes, Captain."

"Why would she be doing that, Computer?"

"Well, Captain...we are alone, aren't we?"

"Completely."

"You see, Captain, I think the science officer is trying to kill me."

"Kill you...Enhance, please."

"Well, you see, she asked me to adjust the log entry about her spilling the, you know, milkshake, so it said 'Science Officer T'Vau inadvertently spilled the milkshake,' and I told her -- of course I told her I couldn't do that, and she said she was going to get me for that, and ever since..."

The door opened and T'Vau came in. There was an ink marker and a soldering pencil pinning her hair up, and a watercress sandwich leaking mayonnaise down her fingers.

The computer voder was whistling "I Got Plenty o' Nothin'."

"Cease this behavior, Computer," T'Vau said.

"Aye aye," the computer said. "At once, Science Officer."

"T'Vau," Trofimov said, "has the computer shown any signs of malfunction? I mean, new malfunction?"

"I see no sip of malfunction at all, Captain," T'Vau said slowly. "To what do you refer?"

"Doesn't its speech pattern strike you as...odd?"

T'Vau looked at the console. "It is illogical and elliptic, but that is hardly odd for a machine programmed by humans." She pulled the soldering pencil from her hair, tapped it on one of the access panels. "I must see if I can find time to study its programming."

"Yes," the captain said absently, "I know how busy we've all been, these last few weeks..."

"Four hundred sixty-five days, nine hours, forty-one minutes. Now, Captain, if I am not required on the bridge, I shall be in my quarters."

"Of course, T'Vau."

The science officer left the bridge.

The computer said "Uh, Captain Trofimov...that stuff I said earlier? About the science officer? Don't pay any attention to it. We're getting along just great. I mean that sincerely. I'm fine, Lieutenant Commander T'Vau's fine, we're all fine."

"That's fi -- wonderful, Computer." Trofimov felt a sudden sharp pain from her hands, looked down. Her fingernails were pressed deeply into her palms.

She faced the main display. It was showing a tape of waves breaking on a seashore, amber-colored waves under double suns, one red, one golden. It was really very restful. She settled back to watch, and soon all sense of time was gone.

"Excuse me, Captain Trofimov," Smith's computer said abruptly.

"What is it now?"

"I don't want to bother you, Captain."

"That's all right, Computer."

"Really, Captain Trofimov, if you're busy."

"I'm not busy."

"But I'm sure you've got a lot of important things to do."

"No. Really.

"It's very nice of you to make time for me, Captain. I understand how difficult it can be, being in sole command of -- "

"Spill it, 'puter!"

"I knew I was being a nuisance. I'm sorry, Captain."

Trofimov held her breath and counted to ten. "Computer."

"Happy to be working."

"Was there something you wanted to tell me?"

"Oh. Yes, Captain. Sensors are picking up Hecht radiation."

"Very well," Trofimov said automatically. "What?"

"When relatively pure dilithium deposits receive solar radiation," the computer said patiently, "they re-emit a particular signature of energy known as Hecht radiation, named for -- "

"I know that, damn it! Put it up on the board!"

A local stellar map appeared on the main display, with graphs alongside showing the radiation-spectrum analysis. There, in glorious color, was the telltale mark of dilithium. in the sun, way up the electromagnetic scale with a sizable i-component.

The captain hit the intercom switch. "T'Vau, Tellihu, get up to the bridge on the double. We're going home."

Copyright © 1987 by John M. Ford

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details