Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

Firestarter

| Author: | Stephen King |

| Publisher: |

Macdonald & Co. Ltd, 1980 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Horror |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Psychic Abilities Man-Made Horrors Monsters |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

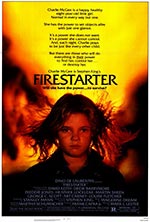

Film & Television Adaptations

Synopsis

Andy McGee and Vicky Tomlinson were once college students looking to make some extra cash, volunteering as test subjects for an experiment orchestrated by the clandestine government organization known as The Shop. But the outcome unlocked exceptional latent psychic talents for the two of them--manifesting in even more terrifying ways when they fell in love and had a child. Their daughter, Charlie, has been gifted with the most extraordinary and uncontrollable power ever seen--pyrokinesis, the ability to create fire with her mind.

Now the merciless agents of The Shop are in hot pursuit to apprehend this unexpected genetic anomaly for their own diabolical ends by any means necessary... including violent actions that may well ignite the entire world around them as Charlie retaliates with a fury of her own....

Excerpt

New York/Albany

1

"Daddy, I'm tired," the little girl in the red pants and the green blouse said fretfully. "Can't we stop?"

"Not yet, honey."

He was a big, broad-shouldered man in a worn and scuffed corduroy jacket and plain brown twill slacks. He and the little girl were holding hands and walking up Third Avenue in New York City, walking fast, almost running. He looked back over his shoulder and the green car was still there, crawling along slowly in the curbside lane.

"Please, Daddy. Please."

He looked at her and saw how pale her face was. There were dark circles under her eyes. He picked her up and sat her in the crook of his arm, but he didn't know how long he could go on like that. He was tired, too, and Charlie was no lightweight anymore.

It was five-thirty in the afternoon and Third Avenue was clogged. They were crossing streets in the upper Sixties now, and these cross streets were both darker and less populated.... But that was what he was afraid of.

They bumped into a lady pushing a walker full of groceries. "Look where you're goin, whyn't ya?" she said, and was gone, swallowed in the hurrying crowds.

His arm was getting tired, and he switched Charlie to the other one. He snatched another look behind, and the green car was still there, still pacing them, about half a block behind. There were two men in the front seat and, he thought, a third in the back.

What do I do now?

He didn't know the answer to that. He was tired and scared and it was hard to think. They had caught him at a bad time, and the bastards probably knew it. What he wanted to do was just sit down on the dirty curbing and cry out his frustration and fear. But that was no answer. He was the grownup. He would have to think for both of them.

What do we do now?

No money. That was maybe the biggest problem, after the fact of the men in the green car. You couldn't do anything with no money in New York. People with no money disappeared in New York; they dropped into the sidewalks, never to be seen again.

He looked back over his shoulder, saw the green car was a little closer, and the sweat began to run down his back and his arms a little faster. If they knew as much as he suspected they did--if they knew how little of the push he actually had left--they might try to take him right here and now. Never mind all the people, either. In New York, if it's not happening to you, you develop this funny blindness. Have they been charting me? Andy wondered desperately. If they have, they know, and it's all over but the shouting. If they had, they knew the pattern. After Andy got some money, the strange things stopped happening for a while. The things they were interested in.

Keep walking.

Sho, boss. Yassuh, boss. Where?

He had gone into the bank at noon because his radar had been alerted--that funny hunch that they were getting close again. There was money in the bank, and he and Charlie could run on it if they had to. And wasn't that funny? Andrew McGee no longer had an account at the Chemical Allied Bank of New York, not personal checking, not business checking, not savings. They had all disappeared into thin air, and that was when he knew they really meant to bring the hammer down this time. Had all of that really been only five and a half hours ago?

But maybe there was a tickle left. Just one little tickle. It had been nearly a week since the last time--that presuicidal man at Confidence Associates who had come to the regular Thursday-night counseling session and then begun to talk with an eerie calmness about how Hemingway had committed suicide. And on the way out, his arm casually around the presuicidal man's shoulders, Andy had given him a push. Now, bitterly, he hoped it had been worth it. Because it looked very much as if he and Charlie were going to be the ones to pay. He almost hoped an echo--

But no. He pushed that away, horrified and disgusted with himself. That was nothing to wish on anybody.

One little tickle, he prayed. That's all, God, just one little tickle. Enough to get me and Charlie out of this jam.

And oh God, how you'll pay... plus the fact that you'll be dead for a month afterward, just like a radio with a blown tube. Maybe six weeks. Or maybe really dead, with your worthless brains leaking out your ears. What would happen to Charlie then?

They were coming up on Seventieth Street and the light was against them. Traffic was pouring across and pedestrians were building up at the corner in a bottleneck. And suddenly he knew this was where the men in the green car would take them. Alive if they could, of course, but if it looked like trouble... well, they had probably been briefed on Charlie, too.

Maybe they don't even want us alive anymore. Maybe they've decided just to maintain the status quo. What do you do with a faulty equation? Erase it from the board.

A knife in the back, a silenced pistol, quite possibly something more arcane--a drop of rare poison on the end of a needle. Convulsions at the corner of Third and Seventieth. Officer, this man appears to have suffered a heart attack.

He would have to try for that tickle. There was just nothing else.

They reached the waiting pedestrians at the corner. Across the way, DON'T WALK held steady and seemingly eternal. He looked back. The green car had stopped. The curbside doors opened and two men in business suits got out. They were young and smooth-cheeked. They looked considerably fresher than Andy McGee felt.

He began elbowing his way through the clog of pedestrians, eyes searching frantically for a vacant cab.

"Hey, man--"

"For Christ' sake, fella!"

"Please, mister, you're stepping on my dog--"

"Excuse me... excuse me..." Andy said desperately. He searched for a cab. There were none. At any other time the street would have been stuffed with them. He could feel the men from the green car coming for them, wanting to lay hands on him and Charlie, to take them with them God knew where, the Shop, some damn place, or do something even worse--

Charlie laid her head on his shoulder and yawned.

Andy saw a vacant cab.

"Taxi! Taxi!" he yelled, flagging madly with his free hand.

Behind him, the two men dropped all pretense and ran.

The taxi pulled over.

"Hold it!" one of the men yelled. "Police! Police!"

A woman near the back of the crowd at the corner screamed, and then they all began to scatter.

Andy opened the cab's back door and handed Charlie in. He dived in after her. "La Guardia, step on it," he said.

"Hold it, cabby. Police!"

The cab driver turned his head toward the voice and Andy pushed--very gently. A dagger of pain was planted squarely in the center of Andy's forehead and then quickly withdrawn, leaving a vague locus of pain, like a morning headache--the kind you get from sleeping on your neck.

"They're after that black guy in the checkered cap, I think," he said to the cabby.

"Right," the driver said, and pulled serenely away from the curb. They moved down East Seventieth.

Andy looked back. The two men were standing alone at the curb. The rest of the pedestrians wanted nothing to do with them. One of the men took a walkie-talkie from his belt and began to speak into it. Then they were gone.

"That black guy," the driver said, "whadde do? Rob a liquor store or somethin, you think?"

"I don't know," Andy said, trying to think how to go on with this, how to get the most out of this cab driver for the least push. Had they got the cab's plate number? He would have to assume they had. But they wouldn't want to go to the city or state cops, and they would be surprised and scrambling, for a while at least

"They're all a bunch of junkies, the blacks in this city," the driver said. "Don't tell me, I'll tell you."

Charlie was going to sleep. Andy took off his corduroy jacket, folded it, and slipped it under her head. He had begun to feel a thin hope. If he could play this right, it might work. Lady Luck had sent him what Andy thought of (with no prejudice at all) as a pushover. He was the sort that seemed the easiest to push, right down the line: he was white (Orientals were the toughest, for some reason); he was quite young (old people were nearly impossible) and of medium intelligence (bright people were the easiest pushes, stupid ones harder, and with the mentally retarded it was impossible).

"I've changed my mind," Andy said. "Take us to Albany, please."

"Where?" The driver stared at him in the rearview mirror. "Man, I can't take a fare to Albany, you out of your mind?"

Andy pulled his wallet, which contained a single dollar bill. He thanked God that this was not one of those cabs with a bulletproof partition and no way to contact the driver except through a money slot. Open contact always made it easier to push. He had been unable to figure out if that was a psychological thing or not, and right now it was immaterial.

"I'm going to give you a five-hundred-dollar bill," Andy said quietly, "to take me and my daughter to Albany. Okay?"

"Jeee-sus, mister--"

Andy stuck the bill into the cabby's hand, and as the cabby looked down at it, Andy pushed... and pushed hard. For a terrible second he was afraid it wasn't going to work, that there was simply nothing left, that he had scraped the bottom of the barrel when he had made the driver see the nonexistent black man in the checkered cab.

Then the feeling came--as always accompanied by that steel dagger of pain. At the same moment, his stomach seemed to take on weight and his bowels locked in sick, gripping agony. He put an unsteady hand to his face and wondered if he was going to throw up... or die. For that one moment he wanted to die, as he always did when he overused it--use it, don't abuse it, the sign-off slogan of some long-ago disc jockey echoing sickly in his mind--whatever "it" was. If at that very moment someone had slipped a gun into his hand--

Then he looked sideways at Charlie, Charlie sleeping, Charlie trusting him to get them out of this mess as he had all the others, Charlie confident he would be there when she woke up. Yes, all the messes, except it was all the same mess, the same fucking mess, and all they were doing was running again. Black despair pressed behind his eyes.

The feeling passed... but not the headache. The headache would get worse and worse until it was a smashing weight, sending red pain through his head and neck with every pulsebeat. Bright lights would make his eyes water helplessly and send darts of agony into the flesh just behind his eyes. His sinuses would close and he would have to breathe through his mouth. Drill bits in his temples. Small noises magnified, ordinary noises as loud as jackhammers, loud noises insupportable. The headache would worsen until it felt as if his head were being crushed inside an inquisitor's lovecap. Then it would even off at that level for six hours, or eight, or maybe ten. This time he didn't know. He had never pushed it so far when he was so close to drained. For whatever length of time he was in the grip of the headache, he would be next to helpless. Charlie would have to take care of him. God knew she had done it before... but they had been lucky. How many times could you be lucky?

"Gee, mister, I don't know--"

Which meant he thought it was law trouble.

"The deal only goes as long as you don't mention it to my little girl," Andy said. "The last two weeks she's been with me. Has to be back with her mother tomorrow morning."

"Visitation rights," the cabby said. "I know all about it."

"You see, I was supposed to fly her up."

"To Albany? Probably Ozark, am I right?"

"Right. Now, the thing is, I'm scared to death of flying. I know how crazy that sounds, but it's true. Usually I drive her back up, but this time my ex-wife started in on me, and... I don't know." In truth, Andy didn't. He had made up the story on the spur of the moment and now it seemed to be headed straight down a blind alley. Most of it was pure exhaustion.

"So I drop you at the old Albany airport, and as far as Moms knows, you flew, right?"

"Sure." His head was thudding.

"Also, so far as Moms knows, you're no plucka-plucka-plucka, am I four oh?"

"Yes." Plucka-plucka-plucka? What was that supposed to mean? The pain was getting bad.

"Five hundred bucks to skip a plane ride," the driver mused.

"It's worth it to me," Andy said, and gave one last little shove. In a very quiet voice, speaking almost into the cabby's ear, he added, "And it ought to be worth it to you."

"Listen," the driver said in a dreamy voice. "I ain't turning down no five hundred dollars. Don't tell me, I'll tell you."

"Okay," Andy said, and settled back. The cab driver was satisfied. He wasn't wondering about Andy's half-baked story. He wasn't wondering what a seven-year-old girl was doing visiting her father for two weeks in October with school in. He wasn't wondering about the fact that neither of them had so much as an overnight bag. He wasn't worried about anything. He had been pushed.

Now Andy would go ahead and pay the price.

He put a hand on Charlie's leg. She was fast asleep. They had been on the go all afternoon--ever since Andy got to her school and pulled her out of her second-grade class with some half-remembered excuse... grandmother's very ill... called home... sorry to have to take her in the middle of the day. And beneath all that a great, swelling relief. How he had dreaded looking into Mrs. Mishkin's room and seeing Charlie's seat empty, her books stacked neatly inside her desk: No, Mr. McGee... she went with your friends about two hours ago... they had a note from you... wasn't that all right? Memories of Vicky coming back, the sudden terror of the empty house that day. His crazy chase after Charlie. Because they had had her once before, oh yes.

But Charlie had been there. How close had it been? Had he beaten them by half an hour? Fifteen minutes? Less? He didn't like to think about it. He had got them a late lunch at Nathan's and they had spent the rest of the afternoon just going--Andy could admit to himself now that he had been in a state of blind panic--riding subways, buses, but mostly just walking. And now she was worn out.

He spared her a long, loving look. Her hair was shoulder length, perfect blond, and in her sleep she had a calm beauty. She looked so much like Vicky that it hurt. He closed his own eyes.

In the front seat, the cab driver looked wonderingly at the five-hundred-dollar bill the guy had handed him. He tucked it away in the special belt pocket where he kept all of his tips. He didn't think it was strange that this fellow in the back had been walking around New York with a little girl and a five-hundred-dollar bill in his pocket. He didn't wonder how he was going to square this with his dispatcher. All he thought of was how excited his girlfriend, Glyn, was going to be. Glynis kept telling him that driving a taxi was a dismal, unexciting job. Well, wait until she saw his dismal, unexciting five-hundred-dollar bill.

In the back seat, Andy sat with his head back and his eyes closed. The headache was coming, coming, as inexorable as a riderless black horse in a funeral cortege. He could hear the hoofbeats of that horse in his temples: thud... thud... thud.

On the run. He and Charlie. He was thirty-four years old and until last year he had been an instructor of English at Harrison State College in Ohio. Harrison was a sleepy little college town. Good old Harrison, the very heart of mid-America. Good old Andrew McGee, fine, upstanding young man. Remember the riddle? Why is a farmer the pillar of his community? Because he's always outstanding in his field.

Thud, thud, thud, riderless black horse with red eyes coming down the halls of his mind, ironshod hooves digging up soft gray clods of brain tissue, leaving hoofprints to fill up with mystic crescents of blood.

The cabby had been a pushover. Sure. An outstanding cab driver.

He dozed and saw Charlie's face. And Charlie's face became Vicky's face.

Andy McGee and his wife, pretty Vicky. They had pulled her fingernails out, one by one. They had pulled out four of them and then she had talked. That, at least, was his deduction. Thumb, index, second, ring. Then: Stop. I'll talk. I'll tell you anything you want to know. Just stop the hurting. Please. So she had told. And then... perhaps it had been an accident... then his wife had died. Well, some things are bigger than both of us, and other things are bigger than all of us.

Things like the Shop, for instance.

Thud, thud, thud, riderless black horse coming on, coming on, and coming on: behold, a black horse.

Andy slept.

And remembered.

2

The man in charge of the experiment was Dr. Wanless. He was fat and balding and had at least one rather bizarre habit.

"We're going to give each of you twelve young ladies and gentlemen an injection," he said, shredding a cigarette into the ashtray in front of him. His small pink fingers plucked at the thin cigarette paper, spilling out neat little cones of golden-brown tobacco. "Six of these injections will be water. Six of them will be water mixed with a tiny amount of a chemical compound which we call Lot Six. The exact nature of this compound is classified, but it is essentially an hypnotic and mild hallucinogenic. Thus you understand that the compound will be administered by the double-blind method... which is to say, neither you nor we will know who has gotten a clear dose and who has not until later. The dozen of you will be under close supervision for forty-eight hours following the injection. Questions?"

There were several, most having to do with the exact composition of Lot Six--that word classified was like putting bloodhounds on a convict's trail. Wanless slipped these questions quite adroitly. No one had asked the question twenty-two-year-old Andy McGee was most interested in. He considered raising his hand in the hiatus that fell upon the nearly deserted lecture hall in Harrison's combined Psychology/Sociology building and asking, Say, why are you ripping up perfectly good cigarettes like that? Better not to. Better to let the imagination run on a free rein while this boredom went on. He was trying to give up smoking. The oral retentive smokes them; the anal retentive shreds them. (This brought a slight grin to Andy's lips, which he covered with a hand.) Wanless's brother had died of lung cancer and the doctor was symbolically venting his aggressions on the cigarette industry. Or maybe it was just one of those flamboyant tics that college professors felt compelled to flaunt rather than suppress. Andy had one English teacher his sophomore year at Harrison (the man was now mercifully retired) who sniffed his tie constantly while lecturing on William Dean Howells and the rise of realism.

"If there are no more questions, I'll ask you to fill out these forms and will expect to see you promptly at nine next Tuesday."

Two grad assistants passed out photocopies with twenty-five ridiculous questions to answer yes or no. Have you ever undergone psychiatric counseling?--#8. Do you believe you have ever had an authentic psychic experience?--#14. Have you ever used hallucinogenic drugs?--#18. After a slight pause, Andy checked "no" to that one, thinking, In this brave year 1969 who hasn't used them?

He had been put on to this by Quincey Tremont, the fellow he had roomed with in college. Quincey knew that Andy's financial situation wasn't so hot. It was May of Andy's senior year; he was graduating fortieth in a class of five hundred and six, third in the English program. But that didn't buy no potatoes, as he had told Quincey, who was a psych major. Andy had a GA lined up for himself starting in the fall semester, along with a scholarship-loan package that would be just about enough to buy groceries and keep him in the Harrison grad program. But all of that was fall, and in the meantime there was the summer hiatus. The best he had been able to line up so far was a responsible, challenging position as an Arco gas jockey on the night shift.

"How would you feel about a quick two hundred?" Quincey had asked.

Andy brushed long, dark hair away from his green eyes and grinned. "Which men's room do I set up my concession in?"

"No, it's a psych experiment," Quincey said. "Being run by the Mad Doctor, though. Be warned."

"Who he?"

"Him Wanless, Tonto. Heap big medicine man in-um Psych Department."

"Why do they call him the Mad Doctor?"

"Well," Quincey said, "he's a rat man and a Skinner man both. A behaviorist. The behaviorists are not exactly being overwhelmed with love these days."

"Oh," Andy said, mystified.

"Also, he wears very thick little rimless glasses, which makes him look quite a bit like the guy that shrank the people in Dr. Cyclops. You ever see that show?"

Andy, who was a late-show addict, had seen it, and felt on safer ground. But he wasn't sure he wanted to participate in any experiments run by a prof who was classified as a.) a rat man and b.) a Mad Doctor.

"They're not trying to shrink people, are they?" he asked.

Quincey had laughed heartily. "No, that's strictly for the special-effects people who work on the B horror pictures," he said. "The Psych Department has been testing a series of low-grade hallucinogens. They're working with the U.S. Intelligence Service."

"CIA?" Andy asked.

"Not CIA, DIA, or NSA," Quincey said. "Lower profile than any of them. Have you ever heard of an outfit called the Shop?"

"Maybe in a Sunday supplement or something. I'm not sure."

Quincey lit his pipe. "These things work in about the same way all across the board," he said. "Psychology, chemistry, physics, biology... even the sociology boys get some of the folding green. Certain programs are subsidized by the government. Anything from the mating ritual of the tsetse fly to the possible disposal of used plutonium slugs. An outfit like the Shop has to spend all of its yearly budget to justify a like amount the following year."

"That shit troubles me mightily," Andy said.

"It troubles almost any thinking person," Quincey said with a calm, untroubled smile. "But the train just keeps rolling. What does our intelligence branch want with low-grade hallucinogens? Who knows? Not me. Not you. Probably they don't, either. But the reports look good in closed committees come budget-renewal time. They have their pets in every department. At Harrison, Wanless is their pet in the Psych Department"

"The administration doesn't mind?"

"Don't be naive, my boy." He had his pipe going to his satisfaction and was puffing great stinking clouds of smoke out into the ratty apartment living room. His voice accordingly became more rolling, more orotund, more Buckleyesque. "What's good for Wanless is good for the Harrison Psychology Department, which next year will have its very own building--no more slumming with those sociology types. And what's good for Psych is good for Harrison State College. And for Ohio. And all that blah-blah."

"Do you think it's safe?"

"They don't test it on student volunteers if it isn't safe," Quincey said. "If they have even the slightest question, they test it on rats and then on convicts. You can be sure that what they're putting into you has been put into roughly three hundred people before you, whose reactions have been carefully monitored."

"I don't like this business about the CIA--"

"The Shop."

"What's the difference?" Andy asked morosely. He looked at Quincey's poster of Richard Nixon standing in front of a crunched-up used car. Nixon was grinning, and a stubby V-for-victory poked up out of each clenched fist. Andy could still hardly believe the man had been elected president less than a year ago.

"Well, I thought maybe you could use the two hundred dollars, that's all."

"Why are they paying so much?" Andy asked suspiciously.

Quincey threw up his hands. "Andy, it is the government's treat! Can't you follow that? Two years ago the Shop paid something like three hundred thousand dollars for a feasibility study on a mass-produced exploding bicycle--and that was in the Sunday Times. Just another Vietnam thing, I guess, although probably nobody knows for sure. Like Fibber McGee used to say, 'It seemed like a good idea at the time.' " Quincey knocked out his pipe with quick, jittery movements. "To guys like that, every college campus in America is like one big Macy's. They buy a little here, do a little window-shopping there. Now if you don't want it--"

"Well, maybe I do. Are you going in on it?"

Quincey had to smile. His father ran a chain of extremely successful menswear stores in Ohio and Indiana. "Don't need two hundred that bad," he said. "Besides, I hate needles."

"Oh."

"Look, I'm not trying to sell it, for Chrissakes; you just looked sort of hungry. The chances are fifty-fifty you'll be in the control group, anyway. Two hundred bucks for taking on water. Not even tapwater, mind you. Distilled water."

"You can fix it?"

"I date one of Wanless's grad assistants," Quincey said. "They'll have maybe fifty applications, many of them brownnosers who want to make points with the Mad Doctor--"

"I wish you'd stop calling him that."

"Wanless, then," Quincey said, and laughed. "He'll see that the apple polishers are weeded out personally. My girl will see that your application goes into his 'in' basket. After that, dear man, you are on your own."

So he had made out the application when the notice for volunteers went up on the Psych Department bulletin board. A week after turning it in, a young female GA (Quincey's girlfriend, for all Andy knew) had called on the phone to ask him some questions. He told her that his parents were dead; that his blood type was O; that he had never participated in a Psychology Department experiment before; that he was indeed currently enrolled in Harrison as an undergraduate, class of '69, in fact, and carrying more than the twelve credits needed to classify him as a full-time student. And yes, he was past the age of twenty-one and legally able to enter into any and all covenants, public and private.

A week later he had received a letter via campus mail telling him he had been accepted and asking for his signature on a release form. Please bring the signed form to Room 100, Jason Gearneigh Hall, on May the 6th.

And here he was, release form passed in, the cigarette-shredding Wanless departed (and he did indeed look a bit like the mad doctor in that Cyclops movie), answering questions about his religious experiences along with eleven other undergrads. Did he have epilepsy? No. His father had died suddenly of a heart attack when Andy was eleven. His mother had been killed in a car accident when Andy was seventeen--a nasty, traumatic thing. His only close family connection was his mother's sister, Aunt Cora, and she was getting well along in years.

He went down the column of questions, checking NO, NO, NO. He checked only one yes question: Have you ever suffered a fracture or serious sprain? If yes, specify. In the space provided, he scribbled the fact that he had broken his left ankle sliding into second base during a Little League game twelve years ago.

He went back over his answers, trailing lightly upward with the tip of his Bic. That was when someone tapped him on the shoulder and a girl's voice, sweet and slightly husky, asked, "Could I borrow that if you're done with it? Mine went dry."

"Sure," he said, turning to hand it to her. Pretty girl. Tall. Light-auburn hair, marvelously clear complexion. Wearing a powder-blue sweater and a short skirt. Good legs. No stockings. Casual appraisal of the future wife.

He handed her his pen and she smiled her thanks. The overhead lights made copper glints in her hair, which had been casually tied back with a wide white ribbon, as she bent over her form again.

He took his form up to the GA at the front of the room. "Thank you," the GA said, as programmed as Robbie the Robot. "Room Seventy, Saturday morning, nine A.M. Please be on time."

"What's the countersign?" Andy whispered hoarsely.

The grad assistant laughed politely.

Andy left the lecture hall, started across the lobby toward the big double doors (outside, the quad was green with approaching summer, students passing desultorily back and forth), and then remembered his pen. He almost let it go; it was only a nineteen-cent Bic, and he still had his final round of prelims to study for. But the girl had been pretty, maybe worth chatting up, as the British said. He had no illusions about his looks or his line, which were both pretty nondescript, or about the girl's probable status (pinned or engaged), but it was a nice day and he was feeling good. He decided to wait. At the very least, he would get another look at those legs.

She came out three or four minutes later, a few notebooks and a text under her arm. She was very pretty indeed, and Andy decided her legs had been worth waiting for. They were more than good; they were spectacular.

"Oh, there you are," she said, smiling.

"Here I am," said Andy McGee. "What did you think of that?"

"I don't know," she said. "My friend said these experiments go on all the time--she was in one last semester with those J. B. Rhine ESP cards and got fifty dollars for it even though she missed almost all of them. So I just thought--" She finished the thought with a shrug and flipped her coppery hair neatly back over her shoulders.

"Yeah, me too," he said, taking his pen back. "Your friend in the Psych Department?"

"Yes," she said, "and my boyfriend, too. He's in one of Dr. Wanless's classes, so he couldn't get in. Conflict of interest or something."

Boyfriend. It stood to reason that a tall, auburn-haired beauty like this had one. That was the way the world turned.

"What about you?" she asked.

"Same story. Friend in the Psych Department. I'm Andy, by the way. Andy McGee."

"I'm Vicky Tomlinson. And a little nervous about this, Andy McGee. What if I go on a bad trip or something?"

"This sounds like pretty mild stuff to me. And even if it is acid, well... lab acid is different from the stuff you can pick up on the street, or so I've heard. Very smooth, very mellow, and administered under very calm circumstances. They'll probably pipe in Cream or Jefferson Airplane." Andy grinned.

"Do you know much about LSD?" she asked with a little corner-wise grin that he liked very much.

"Very little," he admitted. "I tried it twice--once two years ago, once last year. In some ways it made me feel better. It cleaned out my head... at least, that's what it felt like. Afterward, a lot of the old crud just seemed to be gone. But I wouldn't want to make a steady habit of it. I don't like feeling so out of control of myself. Can I buy you a Coke?"

"All right," she agreed, and they walked over to the Union building together.

He ended up buying her two Cokes, and they spent the afternoon together. That evening they had a few beers at the local hangout. It turned out that she and the boyfriend had come to a parting of the ways, and she wasn't sure exactly how to handle it. He was beginning to think they were married, she told Andy; had absolutely forbidden her to take part in the Wanless experiment. For that precise reason she had gone ahead and signed the release form and was now determined to go through with it even though she was a little scared.

"That Wanless really does look like a mad doctor," she said, making rings on the table with her beer glass.

"How did you like that trick with the cigarettes?"

Vicky giggled. "Weird way to quit smoking, huh?"

He asked her if he could pick her up on the morning of the experiment, and she had agreed gratefully.

"It would be good to go into this with a friend," she said, and looked at him with her direct blue eyes. "I really am a little scared, you know. George was so--I don't know, adamant."

"Why? What did he say?"

"That's just it," Vicky said. "He wouldn't really tell me anything, except that he didn't trust Wanless. He said hardly anyone in the department does, but a lot of them sign up for his tests because he's in charge of the graduate program. Besides, they know it's safe, because he just weeds them out again."

He reached across the table and touched her hand. "We'll both probably get the distilled water, anyway," he said "Take it easy, kiddo. Everything's fine."

But as it turned out, nothing was fine. Nothing.

Copyright © 1980 by Stephen King

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details