Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

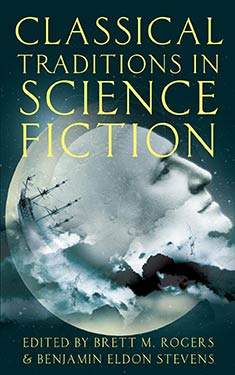

Classical Traditions in Science Fiction

| Author: | Brett M. Rogers Benjamin Eldon Stevens |

| Publisher: |

Oxford University Press, 2015 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Non-Fiction |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

For all its concern with change in the present and future, science fiction is deeply rooted in the past and, surprisingly, engages especially deeply with the ancient world. Indeed, both as an area in which the meaning of "classics" is actively transformed and as an open-ended set of texts whose own 'classic' status is a matter of ongoing debate, science fiction reveals much about the roles played by ancient classics in modern times. Classical Traditions in Science Fiction is the first collection dedicated to the rich study of science fiction's classical heritage, offering a much-needed mapping of its cultural and intellectual terrain.

This volume discusses a wide variety of representative examples from both classical antiquity and the past four hundred years of science fiction, beginning with science fiction's "rosy-fingered dawn" and moving toward the other-worldly literature of the present day. As it makes its way through the eras of science fiction, Classical Traditions in Science Fiction exposes the many levels on which science fiction engages the ideas of the ancient world, from minute matters of language and structure to the larger thematic and philosophical concerns.

Excerpt

Introduction: The Past is an Undiscovered Country

Brett M. Rogers and Benjamin Eldon Stevens

If what we call "science fiction" begins with Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (published in 1818, revised in 1831), then we cannot help but wonder at Shelley's allusion, before the story even begins, to a decidedly ancient figure: the novel is subtitled "The Modern Prometheus" (see Figure 1).[i] This recalls the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus, the Titan who stole fire from the gods and gave it to humankind (e.g., Hesiod's Theogony, Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound); in one version of the myth (Plato's Protagoras), fire was our unique "gift," analogous to other animals' claws, thick hides, or ferocious speeds. Since the myth of Prometheus may be read as an explanatory account and as a symbol for the ongoing human relationship to technology, Shelley's subtitle further implies that Frankenstein will share with Greco-Roman literature and with mythology more generally an interest in the question of how "technology" of different types helps define human culture and, through it, our relationships to the natural world.[ii] That question, among the most crucial that are facing modern life, is of course of central importance to the novel. It is worth emphasizing that already, from this perspective, Frankenstein raises that question about modern life, life in a post-industrial and technoscientific world, first of all by invoking a story from an ancient culture, from a time that was pre-industrial and that would seem not to have been "technoscientific" in anything like a modern sense.

This first example of a classical presence in Frankenstein becomes even more interesting when we dig a little deeper. In its historical context, Shelley's subtitle recalls Greco-Roman antiquity through at least one modern intermediary. The phrase "The Prometheus of modern times" had been made famous by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in a 1756 reference to the American experimentalist Benjamin Franklin (Fortgesetzte Betrachtung der seit einiger Zeit wahrgenommenen Erderschütterungen, vol. 1, p. 472). From this perspective, Shelley's engagement with ancient literature (and subsequently Frankenstein's raising of that ancient question) is neither simple nor straightforward, as if Shelley had reached back to the ancient myth directly. Instead, Frankenstein's use of Prometheus is complicated by its dependence on other modern uses of ancient materials. As Kant's phrase suggests, no longer in ancient myth alone, but now in living memory, too, has a man stolen lightning from the sky.[iii]

Already in its subtitle, then, Shelley's Frankenstein draws attention to its status as a part of a classical tradition, enabling Shelley to locate a pressing concern within a longstanding stream of thought extending from Hesiod through Kant.[iv] We may rather (or also) view Shelley's subtitle as an example of classical reception, emphasizing how Shelley "receives" and brings together several threads in a complex and meaningful manner.[v] We see that, at the same point in Shelley's book, the frontispiece (as seen in Figure 1), there is also an epigraph: "Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay/to mould me man? Did I solicit thee/From darkness to promote me?" This epigraph comes from Milton's Paradise Lost (10.743–745). It places the novel in a Christian tradition: from our perspective, a second tradition that in its own right depends in part on the classical tradition, but is of course not identical to it. Insofar as Milton's epic had, by Shelley's time, achieved the status of a Christian 'classic' in English on par with 'pagan' Greek and Latin classics, we see that, again, Frankenstein's manner of classical reception is indeed complicated: not a "direct" contact with classical antiquity, nor a passive acceptance of a simple classical tradition, but an active reception that is mediated by more recent authors, including, just in this brief overview, Kant and Milton.

Frankenstein's engagement with classical antiquity may thus be understood not only in terms of Shelley's own aims, but also (and crucially) in light of how Greco-Roman antiquity had been variously transformed already, prior to Shelley. In this particular case, that process of reception included centuries of Christian literature, mythology, and thought, taking forms seemingly as different from each other as Kant's analytical philosophy and Milton's epic poetry. This brief analysis of Frankenstein's opening could be developed much further, resulting in an even more complex image of this moment in modern classical reception.

More important for our purposes in this introduction, however, is a different kind of complication, represented by the tendentious "if" in our opening sentence: namely, the fact that Shelley's novel has long been identified by scholars and other readers as the starting point of modern science fiction.[vi] That identification is of course not a given, but a matter of energetic debate. But thinking of Frankenstein as a starting point helps us keep somewhat open the definition of "modern science fiction," an openness we believe is useful as we seek to explore modern science fiction for complex points of contact with classical traditions.

This leads us to the more general question of what, precisely, science fiction is. Is it a "genre," a "discourse," a "conversation," or something altogether different? For our purposes, it is more important that any definition of modern science fiction be able to include Frankenstein, even if—or especially if—the novel challenges aspects of the definition, or vice versa. We therefore prefer to leave the question of science fiction's precise definition open, although we anticipate that the sort of study proposed herein will help answer it. In part to signal the openness of the question, we hereafter refer to modern science fiction as "SF." In this we follow many scholars; in particular we aim to be in the spirit of that abbreviation's acknowledged originator, Judith Merril, editor of twelve "Year's Best" anthologies (1955–1967). In the introduction to the 1967 anthology, Merril writes (ix):

Science fiction as a descriptive label has long since lost whatever validity it might once have had. By now it means so many things to so many people that . . . I prefer not to use it at all, when I am talking about stories. SF (or generally, s-f) allows you to think science fiction if you like, while I think science fable or scientific fantasy or speculative fiction, or (once in a rare while, because there's little of it being written, by any rigorous definition) science fiction.

In this way we are able to accept the proposal that Frankenstein inaugurates modern SF. With Frankenstein's status as the starting point at least provisionally in mind, then, and in light of the reading sketched above, we may say that modern SF has, from its very beginning, as it were looked forward to the future and around at the present in part by looking farther back: to Greco-Roman mythology, to the literature of classical antiquity, to images of ancient history. As a locus of classical receptions, modern SF has engaged in historically and formally complex negotiations, not to say contestations, between pre-modern ways of knowing and being human, on one hand, and on the other hand, then-emergent and now-ascendant technoscientific thinking and practice. The complexities of Frankenstein's reception of antiquity are, in our view, suggestive of how modern SF engages with "antiquities" in the plural, that is, with antiquity as it has been received and transformed already into various forms, objects, and products, and is being so transformed even now. In other words, to borrow from Ovid's Metamorphoses, we are interested in the ways modern SF speaks of antiquity's many "changed forms" (mutatas formas) and participates in the production of new (and previously unimaginable) bodies (in noua . . . corpora; 1.1–2).

Our main purpose for both this introduction and the volume as a whole, then, is to suggest some of the ways in which serious discussion of the Janus-like character of modern SF might proceed.[vii] From examples like Frankenstein—as well as from examples unlike it—we think that a wide range of modern SF should be of great interest to anyone already interested in the ancient world and its classics. Moreover, we hope that this volume's chapters demonstrate the relevance of a wide range of Greek and Roman classics for modern SF. Both as an area in which the meanings of classics are actively transformed, and as an open-ended set of texts whose own "classic" status is a matter of ongoing discussion and debate, SF stands to reveal much about the roles played by ancient classics as well as new "classics" in the modern world.[viii] In short, we aim to justify the joint study of Classics and SF, as well as to indicate certain areas that seem to our authors and ourselves to be especially open for immediate exploration. If modern SF is viewed, as we believe it must be, as a crucial and popular mode, even the mainstream mode, of thinking about life in a modern, technoscientific world, then the fact that it is also a site of significant classical receptions should be of real interest.[ix]

With that aim in mind, in this introduction we have three main goals. First, we argue that the discipline of Classics has a stake in the study of SF because of the urgent ethical and epistemological questions SF raises about the humanities vis-à-vis science and technology. The possibility of an interdisciplinary field of study is important especially in light of the potential impact SF may have on popular perceptions of the classics. Second, as a step towards developing that argument, we offer a reading of two influential texts in SF studies: one primarily historical, the other primarily theoretical. Our main point here is that ancient classics and modern science fiction have in common a deep epistemological similarity; that is, a similarity in how each imagines the basic functioning of human knowledge. We conclude that if "the past is a foreign country" (in the words of Hartley) while the future is an "undiscovered country" (in the words of Gorkon), then the joint study of Classics and modern SF may permit us to contemplate simultaneously the (science fictional) future in all of its familiar foreignness and the (classical) past as an undiscovered country.[x]

Third and finally, we conclude this introduction by summarizing the 14 chapters composed for this volume, as each contributes meaningfully to the development of serious, systematic scholarship on the reception of classical antiquities in SF. So far, work in the field of Classics and SF has consisted mainly of studies of individual texts, often published in disparate places.[xi] To our knowledge, to date there have been only two surveys, each partial in its own way: Brown (2008) and Fredericks (1980). The first book-length collection of essays, L'Antiquité dans l'imaginaire contemporain – Fantasy, science-fiction, fantastique, edited by Bost-Fiévet and Provini (2014), has just been released, coming out as this present volume was going to press. It remains the case then, as Brown herself notes, that "the relationship between SF and the Classics is still relatively uncharted territory" (2008: 427).[xii] It is thus our hope that these chapters, ranging widely over texts and other works from antiquity and in modern SF, will work together to chart this territory further, to stimulate discussion and encourage debate about this burgeoning field, and to point to areas for future exploration.

Copyright © 2015 by Brett M. Rogers

Copyright © 2015 by Benjamin Eldon Stevens

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details