![]() Rhondak101

Rhondak101

1/31/2017

![]()

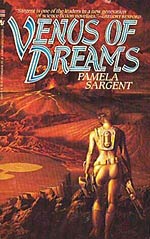

Pamela Sargent's Venus of Dreams (1986) is included on the Easton Press Masterpieces of Science Fiction list and the 200 Significant Books by Women, 1984-2001 list. It deserves these places because it (like all good books) speaks to our contemporary culture. I am not going go rabidly political in this review, but I do have to say reading this book during this period of anti-intellectualism and growing mysogny among our national leaders is quite haunting.

The novel is set in some sort of post-apocalyptic world--I think that it might have been an economic collapse. Anyway, there is a single world economy controlled by different nomarchies. The separate nomarchies contribute to the world economy in different ways, and they all have different customs. For example, the protagonist of the novel lives Lincoln in the Plains of the former United States. She lives in Lincoln. The culture of the plains is matriarchal agarian. The women, using robotic machines, grow the majority of the world's grain. The women live communes of extended families, working and raising their children together. The girls are expected to stay on the family farm and the boys are expected to leave and become nomadic workers who travel from city to city repairing and installing machinery and other such tasks. These "traveling salesmen" types are expected to have sex with the women on the farms who invite them to their beds. If both parties agree, then they will have a child--after the government gives permission, of course. (The local doctor must remove their birth control implants.) This child will be raised by the commune and the father might visit his offspring as he passes through town again. Or, he might not. Levels of parenting for the men in the Plains are varied. Other nomarchies have other customs, such as semi-permanent bonding which is similar to a marriage, in which a child grows up with a nuclear family.

Iris Angharads is a girl of the Plains, growing up in that gynocentric world. She is eight years old at the beginning of the novel, and she is fascinated with the planet Venus and Earth's attempts at terraforming it. Her intellectual curiosity is encouraged by her grandmother Julia and discouraged by her mother Angharad. Iris is a first daughter of a first daughter, so she is expected to take over the commune someday. Her mother does not understand why she wants to learn to read and learn science and all those other useless things that are not going to help her become a better farmer. Her friends and family tease her, call her stuck up, and try to block her studies. Part 1 of the book shows Iris impressing her online teachers, winning the ability to take more classes, and lying to her family about her reasons for doing so. She tells them that learning about climatology will help her be a better farmer, but she really wants to go to Venus and help create a new world.

The next three parts of the book guide Iris through feminist and working class issues, that we talk about today as women and people from working class begin white collar, scientific and academic careers. Many of these issues did not have names in 1986, but we know them now. At school she suffers from imposter syndrome and work-life balance problems. Once she makes it to Venus, she continues to suffer from work-life balance problems and encounters the glass-ceiling.

Iris is single-minded in her goals, and she is very ambitious. These characteristics are part of the reason that the book garners negative reviews. Many of these reviewers talk about how none of the characters are likeable. And it is true there are no "heroes" in this novel. Almost every character is driven, self-centered, and lacks empathy. And they never listen to one another (to the point that it becomes infuriating). In general, the women are portrayed as stronger than the men. The men are generally more emotional. This is not handled sloppily or even too obviously. It is only in reflecting on the novel that I noticed this, which leads me to wonder if these ambitious, driven characters were all men would those reviewers have found them more likeable because they display more "masculine traits."

In general, this book is too long. The latter half drags and gets too bogged down in the politics of Project Venus. There are too many pages of third-person narration that tells us what characters are thinking--there needs to be more dialogue and action.

That being said this is a worthwhile book, even as a cautionary tale about stubborn, single-minded people who need to learn to listen to their family members, accept change, and fight against prejudice of all kinds.

This series continues with Venus of Shadows, which features Iris's children and their attempts to make Venus the world they envision. I am not rushing to read this one since I found Sargent's reimagining of Earth the strongest part of this novel, but I will probably finish the series.