![]() chuhl

chuhl

9/24/2012

![]()

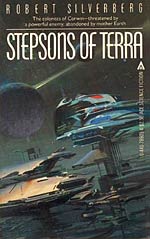

Stepsons of Terra is the story of Baird Ewing, a man on a mission to save his planet. His homeworld, a distant colony of Earth, lies in the path of implacable alien invaders. He travels to Earth, the first of his people to do so in 500 years, to get help, but he is shocked to find that Earthmen are not the resourceful supermen he was expecting. Instead they are weak, decadent and about to succumb to invasion themselves at the hands of the Sirians.

Like one of Alfred Hitchcock's heroes, Ewing runs afoul of the Sirians, who refuse to belief the simple truth that he has come to enlist Earth's help. They jump to the wrong conclusion and assume that Ewing has come to lead a revolution to save Earth.. So they harass, kidnap, and torture him.

In his introduction, Silverberg says that this novel, his sixth, is the first one in which "I was a trifle less flamboyant about making use of the pulp-magazine clichés [such as] feudal overlords swaggering about the stars. Rather, I would write a straightforward science fiction novel, strongly plotted but not unduly weighted towards breathless adventure."

I think Silverberg might have overcompensated, because the first half of the book, shorn of its science fiction trappings, reads like a contemporary pulp fiction thriller (it was written in 1958). Think of it this way: an idealistic man comes from the country to the big city. He's surprised to find that the city is corrupt, all but taken over by the local crime lord while the legitimate authorities are helpless. The crime boss throws a femme fatale his way to pump him for information, and when she fails, the boss kidnaps him and roughs him up. It sounds like a 50s film noir, but that's essentially the story of the first half of the book, gussied up with science fiction tropes like robots and suspended animation and other high tech.

Too bad, because I find that when the story is "weighted towards breathless adventure," things can get pretty exciting. Here's an excerpt in which one character, chased by the police, is determined not to be captured alive. (I've replaced the character's name with "he" to avoid spoilers.)

"Darkness covered the field. He glanced up to see the cause of this sudden eclipse.

A vast ship hung overhead, descending as if operated by a pulley and string. Its jets were thundering, pouring forth flaming gas as it came down for a landing. He smiled at the sight.

It'll be quick, he thought.

He heard the yells of astonishment from the police. They were backing off as the great ship dropped towards the landing area. He ran in a wider circle, trying to compute the orbit of the descending liner.

Like falling into the sun. Hot, quick.

He saw the place where the ship would land. He felt the sudden warmth; he was in the danger zone now. He ran inward, where the air was frying...

"The idiot! He'll get killed!" someone screamed as if from a great distance. Eddies of flaming gas seemed to wash down over him; he heard the booming roar of the ship. Then brightness exploded all about him, and consciousness and pain departed in a microsecond.

The ship touched down."

In the second half of the book, the idea of time travel is introduced, and at that point the book becomes unequivocally science fiction. Ewing travels in time to save himself from the Sirians and finds that it's a bit like cloning yourself: traveling through time creates a duplicate of yourself, and your duplicate doesn't just fade away when his job is done or when the timelines converge. For instance, if Ewing on Wednesday goes back in time to Tuesday to save himself, then when Wednesday rolls around again there are two of him. Which one of the two Ewings is the real one? Or are both equally real? If so, which one picks up their life where it left off? And what happens to the other one? The more Ewing uses time travel, the more Ewings are created, and the dilemmas multiply.

Silverberg uses time travel technology to explore dilemmas of personal identity and responsibility and give a straightforward adventure story a more complex dimension. I do think Silverberg sometimes plays fast and loose with the time paradoxes he creates. Ewing somtimes takes drastic action based on some pretty shaky assumptions. At one point the narrator tells us, "The paradoxes multiplied. The best he could do was ignore them." That's not just the narrator telling us about Ewing, that's Silverberg talking about himself, warning the reader not to expect too rigorous an analysis of the temporal paradoxes. It's not that philosophical a book. But the paradoxes and the issues they raise do add deeper texture to the story.

There's a strain of melancholy that runs throughout the book. Ewing is disillusioned and disappointed right from the start, and his attitude mellows into existential angst as he confronts the ethical dilemmas posed by the existence of multiple selves. He's resolute and doesn't give up, but this is still kind of a downbeat story. It's not a gloomy book, but it's not rollicking pulp-fiction fun, either. I see it as a sort of SF film noir that takes a while for the SF to kick in.