![]() Emil

Emil

3/15/2012

![]()

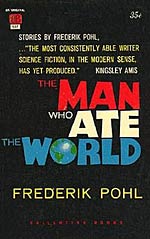

Although Frederik Pohl's work began in the Campbellian era, he has always helped to determine the future of the genre through measured work as en editor, anthologist and writer. He began his career as a magazine editor in 1940 and wrote extensively with Jack Williamson and C.M. Kornbluth.

With Kornbluth he produced the classic The Space Merchants (1953), which describes a future world dominated by advertizing, a theme preceded here by a few years in the stories "The Wizards and The Waging" and "The Waging of the Peace", taking a "slickly ironic" look (to quote John Clute from The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction) at how humans react to everyday commercial products pushed into their faces. It's incredibly fun to read about how the National Electro-Mech fortied factory inundates a smalltown Buick salesmans with new Buicks and how the very same salesman ends up as a recruit in attacking and stopping the production of these cars. These final two stories, arguably the best in the collection, are slightly anti-capitalist satire. Nothing strange here, considering Pohl's short foray in the Young Communist League during the late 1930s. Shortly hereafter - as a side note - he enlisted in the army, and, in weird twist of fate, served with Jack Williamson as weather observer.

The title story "The Man Who Ate The World" is the weakest in the collection and is the only one I remember reading as a youngster. It's a tragic story about this child growing up and trained to consume and consume, without his parents nurturing him. This important part of early childhood development is left to robots. Eventually, as an adult, he continues to consume and build robots to produce robots that destroy robots, ever repeating the cycle of consumption, ultimately threatening the exisiting world order. A psychologist comes to the rescue, reuniting the adult child with his teddy. Yeh, yeh, a cop-out and archaic Freudian psychology, but I did say this is the weakest story in the collection. It does not detract from Pohl's more than subtle jab at American consumerism, that expectation for people to consume, buy, and destroy in order to repeat the cycle. Despite my gripe about the teddy, the story is still fun ... and its insinuation certainly still rings true for modern day consumerism.

"The Snowmen" is my personal favorite, at 8 pages the shortest in the collection, and most bizarre, even cadaverous, hinting at a certain Roald Dahl chromaticity. Pohl skillfully unfolds the whole allegory in which in courting couple invites an alien visitor into the woman's home. Her reputation, it seems, is well-known throughout the exisiting universe. While she entertains the alien, the man plunders and loots the alien craft, with a wonderfully macabre twist at the end.

"The Day The Icicle Works Closed" is about economic manupilation and collapse. A distant planet is cut off from trade and most people resort to renting their bodies to tourists while their minds perform hard labour elsewhere, usually inside gigantic machines, underground, in mines. The scientific mechanism on just how this happen is not explained, but that isn't the point, is it? Pohl sets up a society that are forced to survive through disagreeable means because of economic disparity. So we see some ex-factory workers attempting to kidnap the mayor's sons for ransom instead of whoring out their bodies to reckless and inconsiderate tourists. Ever consdered your own behavior when driving a rental?

In Pohl's novels Jem: The Making of a Utopia (1979) and Man Plus (1976) we meet characters who adapt to their strange environments by losing, or changing their humanity. Although "The Seven Deadly Virtues" do not address the exact same issues we do recognise similar themes. The story is set on Venus and I can't imagine a harsher environment to live in. It's an interesting society featuring a conditioning response to killing - you simply cannot do it. That aside, once you have acclimatized fully to conditions on Venus, there is no leaving. And once society has shunned you, you become a non-person. This happens to a relative new arrival to Venus, who steals the wife of a very powerful man, resulting in his ostracization. Someone else, also shunned, is included in the plot to topple the powerful man. The solution is masterfully done and very plausible.

All in all, this is a stunning collection of six short stories by a master storyteller, and despite them being dated by 50+ years, still quite unique and remarkably prescient, generally poking fun at mass production, consumerism and industrialisation. These stories of social criticism were a blast and expose Frederik Pohl as the hidden hero of SF. Think of him in terms of the Golden Age. He knew them all - who else is still alive?